A young conservative who looks at our country today can be excused for wondering what good his father’s and grandfather’s “conservative movement” has done. OK, we won the Cold War and, more recently, seem to have installed a reliable majority of sane justices on the Supreme Court, but other than that, of the objectives with which gleeful conservatives sent Ronald Reagan to the White House four decades ago, which have they achieved?

Every generation must respond to new challenges of its own, so it is no criticism of the activists of 1964 or 1980 to observe that mindlessly repeating their agenda and tactics will not succeed today. But many conservatives wonder if the problem is deeper. Perhaps the conservative movement — perhaps America itself — was somehow misbegotten. If the institutions, organizations, and leaders collectively derided as “Conservatism, Inc.” have proved impotent in the face of a 70-year cultural and political onslaught from the left, perhaps they were never good at anything besides raising money.

Even if one takes a more forgiving view, it can be tempting to dismiss the old guard as irrelevant. Lincoln urged his contemporaries, “As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew.” Yesterday’s Chamber of Commerce conservatism is no match for the ferocious neo-Marxism that now controls nearly every major American institution. We’re getting mauled on the field while the aging alumni partying in the stands exhort us to win one for the Gipper.

But a recent gathering in Washington of a few old conservative warriors reminded me how distorted that view is.

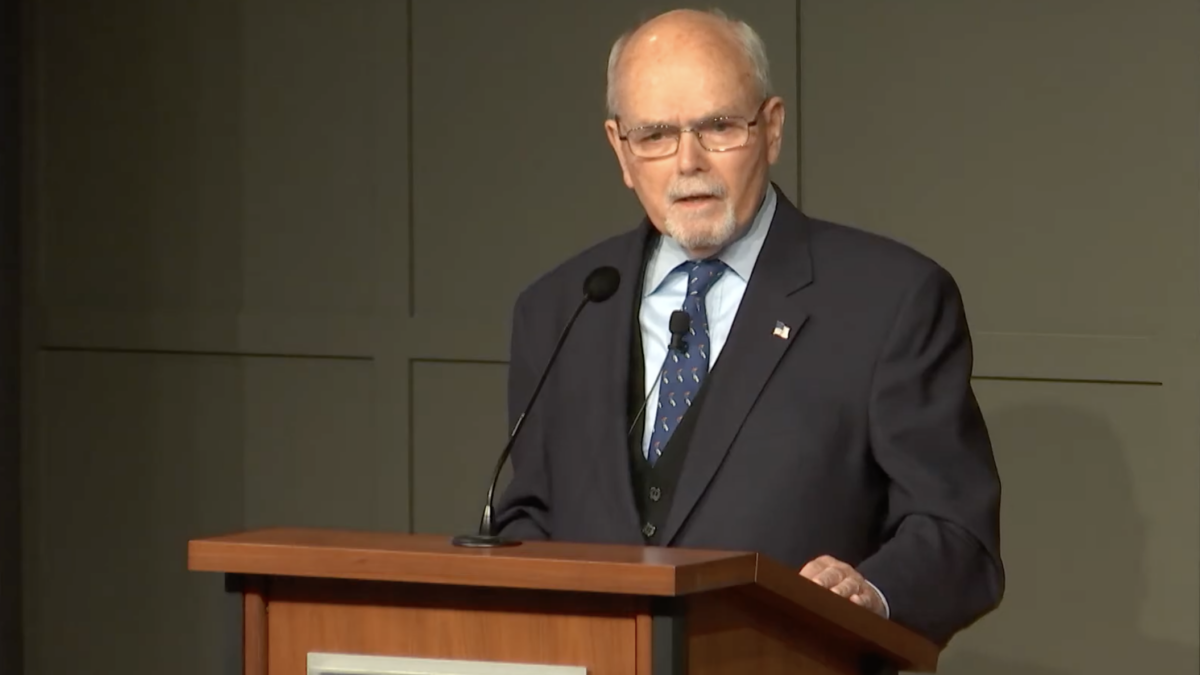

The occasion was the 90th birthday of Lee Edwards, known today as the historian of the conservative movement but himself one of its key players since the early 1960s. By Richard Viguerie’s calculations, Lee is the longest-tenured member of the conservative movement, having moved up to that exalted position upon the death of Phyllis Schlafly.

Richard (who is No. 2) assembled six other veterans — five men and one woman — for a luncheon at the Monocle in Lee’s honor. Founders and leaders of some of the movement’s most important organizations, they have all served the cause since 1964 or earlier. Richard also included two “youngsters,” Tim Goeglein and me.

It’s not often that I’m the pup in the room, but I felt like a high school baseball coach who has somehow found himself hanging out with a bunch of Hall of Famers, listening to tales not only of their own exploits but of time they spent with Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Lee Edwards met Ronald Reagan in 1965 when the movie star was contemplating a run for governor of California. Others talked about their last visit with Bill Buckley before he died.

Lee’s engaging memoir, “Just Right: A Life in Pursuit of Liberty” (2017), tells the story of this remarkable cohort. They came from all over the country and from every kind of background, brought together by their shared anti-communism and their enthusiasm for Barry Goldwater, who “was not so much the candidate of a political party as the personification of a political movement,” Lee recalls.

“He inspired thousands of young people like me to get into politics and form a national network committed to the advancement of conservatism. They included Ed Feulner of the Heritage Foundation; Ed Crane of the Cato Institute; commentator/presidential candidate pat Buchanan; fundraising guru Richard Viguerie; American Conservative Union head David Keene; publisher Al Regnery; Fund for American Studies chairman Randal Teague; Young America’s Foundation president Ron Robinson … and many others.”

Here’s something for a young conservative activist to think about: You can take these institutions for granted because they and a multitude of others have been there all your life. If you are inspired to get into politics, you can choose from scores of organizations that will put you to work, pay you, and, most importantly, train you. Call it “Conservatism, Inc.,” if you want, but in a vast country like ours, with a political system of mind-boggling complexity, institutions — with money — are important. Where would we be without them?

Now consider this: When Lee Edwards and Richard Viguerie and the others answered the call, they were on their own. Apart from a couple of fledgling journals, the conservative movement had no means of spreading its message, training its foot soldiers, developing and promoting credible policies, or doing anything else that a successful political movement does. They had to build everything. And they did.

Has every one of those organizations stayed on track? Has every idea been a good one? Has every penny been well spent? Above all, are we any closer to winning than we were in 1964? I am painfully aware that the answers to those questions are “No,” “No,” “No,” and “Are you kidding?” But two hours with those seven giants refreshed my spirit more than an elusive “red wave” election could do. If only every young conservative could sit at the feet of these happy warriors for an hour or two.

Two months before I was born, Lee Edwards helped to found Young Americans for Freedom. When I was toddler, he was handling communications for the impossibly idealistic Goldwater campaign. And while I was still in grade school, he was launching the crusade that would culminate in the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, which reminds the world that once again fashionable ideology has killed 100 million human beings.

We talk a lot these days about overhauling the political movement that made Ronald Reagan president, and that’s probably necessary. But we would be foolish to despise the patrimony of Lee Edwards and conservatism’s greatest generation, a patrimony not only of institutions but of perseverance, fidelity, fortitude, and patriotism.