As the fear of Covid wanes with its news coverage, one of the remaining vestiges of the narrative involves face coverings. The premier journal Science recently published the largest cluster-randomized trial to date on masks, a massive study that the science community had been calling for since the start of the pandemic.

This study divided rural villages in Bangladesh into those encouraged to wear either medical or cloth masks, or no mask. At the conclusion of the trial, participants volunteered information on whether they experienced “COVID-like symptoms.”

Villagers with self-diagnosed Covid-like symptoms were asked to take an antibody test to determine if they carried SARS-CoV2 antibodies, suggesting they had been infected at some point (i.e., were “seropositive”). The authors concluded that masks reduced “symptomatic seropositivity” by 9.5 percent. In response, The Washington Post triumphantly declared: “We conducted the largest study on masks and COVID-19: They work.”

As with almost everything, the truth is more complicated. In a series of blog posts, University of California at Berkeley engineering professor Ben Recht meticulously detailed why he believes the findings more accurately reflect statistical sleight of hand rather than actionable data: “One of the dark tricks of biostatistics is moving away from absolute case counts to measures of risk such as relative risk reduction, efficacy… all these measures are relative, and they tend to exaggerate effects.”

The Bangladesh study authors did not include the total number of “symptomatic seropositive” villagers in their paper, forcing Recht to calculate those numbers. “There were 1,106 symptomatic individuals confirmed seropositive in the control group (i.e., unmasked) and 1,086 such individuals in the treatment (i.e., cloth or medical mask) group. The difference between the two groups was small: only 20 cases out of over 340,000 individuals over a span of 8 weeks. I have a hard time going from these numbers to the assured conclusions that ‘masks work.’”

Even the prestigious journal Nature reported the study findings in a deceptive way, with a large bold title stating: “Face masks for COVID pass their largest test yet.” However, below the bold title is a less enthusiastic, small-print interpretation of the findings: “A rigorous study finds that surgical masks are highly protective, but cloth masks fall short.”

Alarmingly, the Bangladesh study authors doubled down on their findings: “we persuaded only about a third of the population to change their masking behavior. It is possible that more aggressive efforts could lead to even more change and produce greater health benefits.” Was more “persuasion” (i.e., coercion) really what was lacking in our pandemic response?

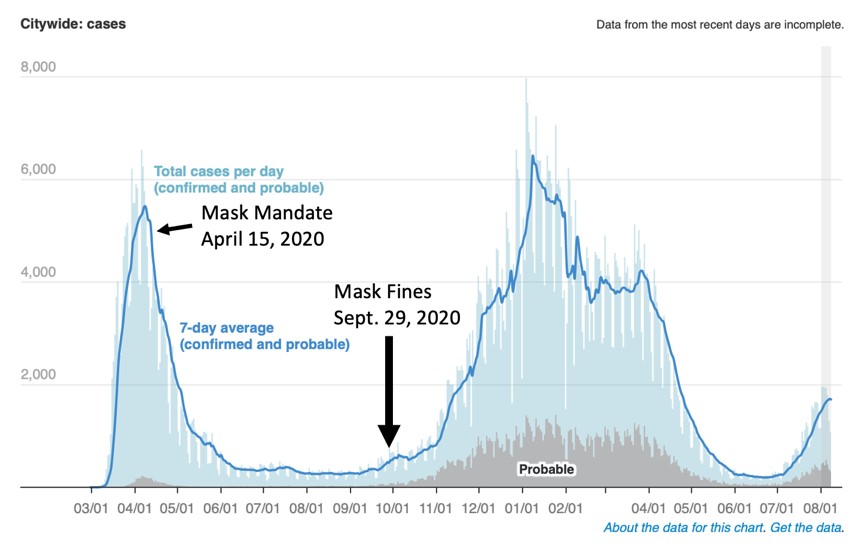

A quick look at data from New York City in 2020 reveals their epidemic curve was already falling before mask mandates were in place, and that coercion in the form of hefty fines did nothing to prevent the next wave, whose peak was higher than that of the previous wave’s pre-mask mandate peak and lasted longer despite the coercive measures.

The bottom line: any policy so intrusive and divisive as forced masking should have significant, indisputable effectiveness in “real-world” application. The largest mask study to date failed in this regard, yet public health authorities and most scientists continue to cling to reflexive health policies, while politicized journalists are complicit in amplifying their one-sided message.