With the left attempting to eradicate vast swathes of history, it’s helpful to rediscover the reality — the failings and foibles, yes, but also the good — behind past generations of Americans. On that count, a new biography of America’s first, and in many respects foremost, Founding Father yields a full portrait of Benjamin Franklin’s life and times.

The four-hour documentary by filmmaker Ken Burns provides additional context about Franklin beyond the well-told tales about lightning and bifocals. A man who arrived in Philadelphia in 1723 with little more than the clothes on his back, Franklin rose up from his bootstraps by hard work and luck, his rise echoing that of the country he would help to create.

Blue Collar Statesman

The documentary focuses on several distinctive facets of Franklin’s life, starting with the working-class roots that distinguish him from other members of the founding generation. A runaway apprentice, Franklin made his initial fortune as a printer — an occupation that required not just good literacy and vocabulary skills to set lines of type, but also the physical strength to manhandle and press heavy metal plates while printing.

The fact that Franklin, unlike most of his peers, ascended into the gentry class on merit rather than by dint of birth makes him, as one historian put it, the most accessible of the Founders. The first episode quotes Franklin from his autobiography discussing his “intrigues with low women” in both London and Philadelphia. Can anyone imagine a Puritan like John Adams, or a Stoic figure like George Washington, ever publicly admitting such bawdy dalliances?

Cosmopolitan Personality

Notwithstanding his blue-collar background, Franklin spent his life soaking up the experiences of other people and cultures. His work as postmaster general meant he traveled widely through the American colonies north and south inspecting postal routes.

Franklin lived in London on three separate occasions, the first when he was but 18, and spent eight-plus years in France. All told, he traveled across the Atlantic eight times during his life — at a time when such a voyage seemed nearly as rare as a trip into space today.

While he had only two years of formal education, Franklin’s innate curiosity led him to become a man of science, earning praise as a modern Prometheus for the way his famous kite experiment helped tame the lightning in the heavens. He attended the coronation of King George III — the monarch whom he would eventually lead a rebellion against — met in person with philosophers like Adam Smith and David Hume, and witnessed some of the first hot-air balloon flights while living in France.

His cosmopolitan air led him to become a revolutionary, albeit at a late stage. In 1754 — when later revolutionaries James Madison and Thomas Jefferson were still children — Franklin helped propose the Albany Plan, a failed proposal for the American colonies to provide for their common defense.

For the following two decades, even as Britain and her American colonies grew apart, he hoped to find the terms that would prevent an irreparable breach. But a searing experience in London’s Cockpit after the Boston Tea Party convinced Franklin of the necessity of a separation from Great Britain, which would never view its colonial subjects as anything other than second-class citizens.

‘A More Perfect Union‘

It seems fitting that Franklin came to embrace the idea of independence for the United States, not least because his scientific experiments made him the only American known the world over at the time of the Revolution. Even more than his Enlightenment-era contemporaries, Franklin continually dedicated himself to improvement — personal improvement, scientific advancement, and civic uplift.

Inventions including the lightning rod and his eponymous stove could have made him a fortune, but Franklin never patented a single one, believing his creations merely repaid the debt he owed inventors who came before him. In his adopted hometown of Philadelphia, he helped found a public library, a fire brigade, and what became the University of Pennsylvania, all in the name of bettering society.

Franklin applied his principles of civic improvement to his personal conduct, echoing the aphorisms of his Poor Richard’s Almanac. He would daily examine whether he had adhered to the virtues he thought necessary for a gentleman. He did not always succeed, particularly when it came to family. He remained overseas for the last decade of his wife’s life, and disowned his son William after the latter remained loyal to the British crown.

But Franklin always tried to improve himself. In his final years, a man who held slaves all his life and as a printer ran advertisements from slaveholders seeking information on runaways, he took a leading role in Pennsylvania’s burgeoning abolition movement, after lamenting his inability to insert a passage condemning human bondage into the new Constitution.

The First Founder

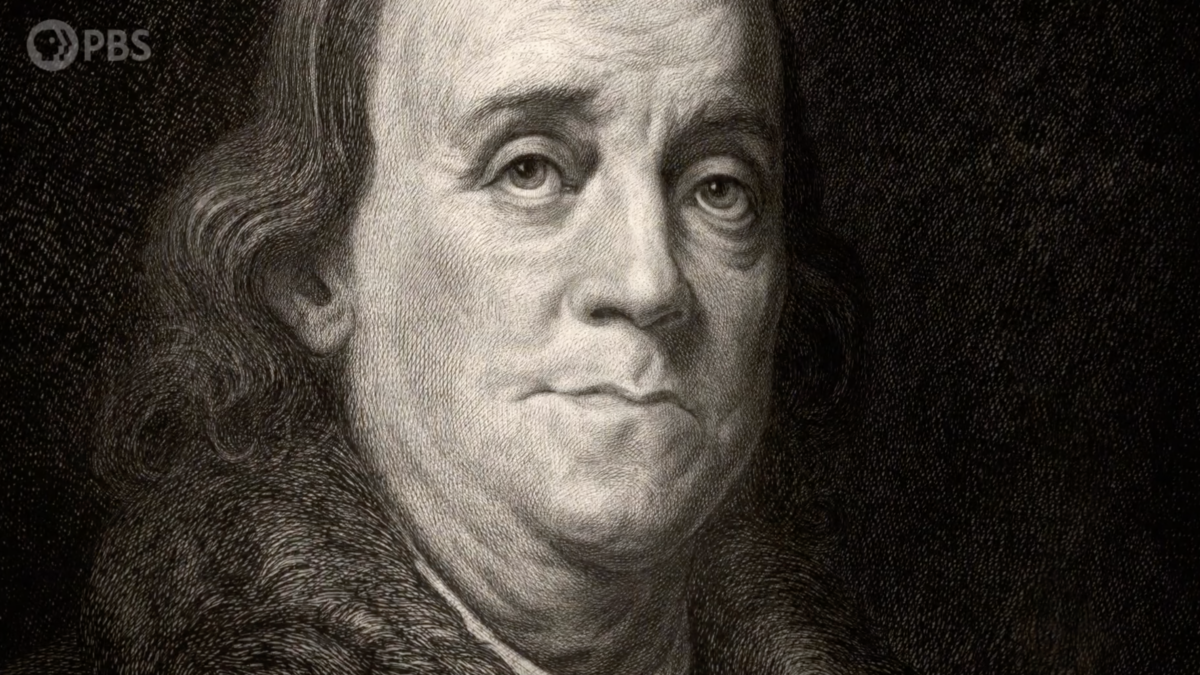

The PBS documentary adapts Burns’s techniques to his 18th-century subject. A biography of a statesman who died half a century before the first Daguerreotypes made photographs — a staple of Burns’ documentaries on the Civil War, baseball, and Muhammad Ali, among others — anachronistic for a Franklin biography. Instead, the producers commissioned a series of woodcuts dramatizing scenes in Franklin’s life, and used the “Ken Burns effect” for these scenes, along with other portraits and paintings depicting the Revolutionary era.

From his homespun advice in print to his famous verdict on the outcome of the Constitutional Convention — “a Republic, if you can keep it” — Benjamin Franklin provided words of wisdom that echo down to Americans yet today. Burns’ documentary helpfully refreshes those words, and that example, for a 21st-century audience.

“Benjamin Franklin” is available on the PBS website or via the PBS app. Check your local listings for re-airings.