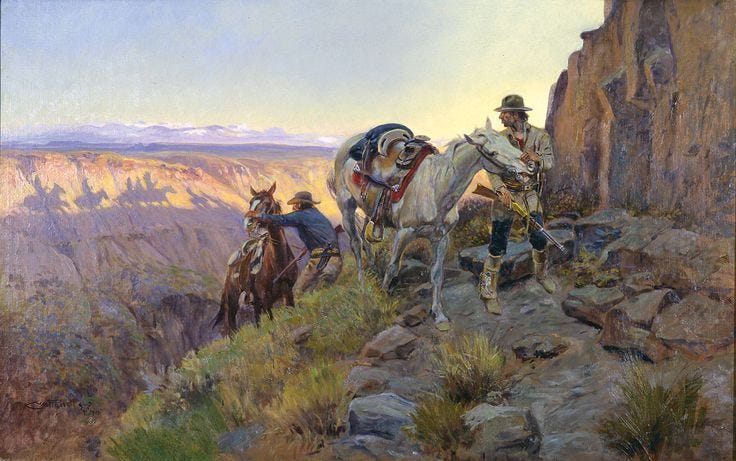

In my home, I have a framed reproduction of Henry W. Hansen’s 1900 painting, “Questionable Companions.” My copy was originally housed in my maternal grandparent’s home, a small, converted cabin nestled amidst the poplars and pine trees on a small lake in north-central Minnesota.

On those rainy days at the lake, when my brothers and I were confined to the house instead of running half-naked through the woods or swimming as far offshore as we dared, I remember looking at that picture and imagining the conversation between the cavalryman and the Indian were having, walking through the faint desert trail.

What had they seen? Where were they going? What adventures were on the horizon? I fell in love with that picture and with it, the Western frontier and what Theodore Roosevelt called “Cowboy-Land.”

I wrote previously about the American Cowboy, but the currents of world events and domestic infighting have brought me back to this picture and the question: Is embracing the America of the frontier the defiant answer to what so many insist is our nation’s inevitable decline into irrelevancy?

Discovering the American Spirit

H.W. Hansen was born in Dithmarschen, Germany, and studied art in England as a young man. He had a promising career ahead in Europe, but he abandoned the Old World and set off for America in 1877.

He was inspired by writer James Fennimore Cooper’s “Leatherstocking Tales” – the adventure of this new nation, one of opportunity, green with an innocent assuredness and brashness that attracted the bold, fearless, and determined soul whose curiosity was whetted by what he read in Cooper’s prose. It was Hansen’s story but rang familiar in the hearts of so many who would look to America — and later the western frontier — as home.

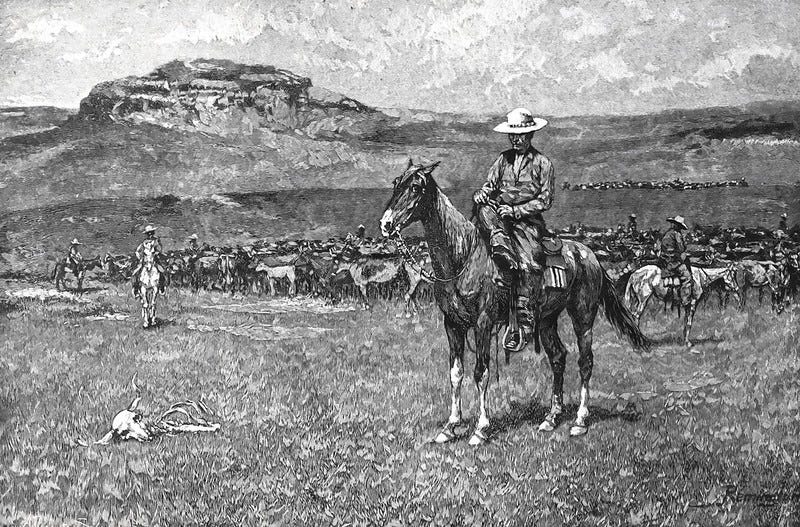

Cooper was frequently called the “Frederic Remington of the West,” a reference to the great American painter and sculptor who made New York and Connecticut his home. Remington, Cooper, and contemporaries Charles Marion Russell, William Keith, and Maynard Dixon brought the images of the West to life. But the true story, where it became inextricable from the myth of the frontier itself, came from those who wrote about it, inspired the men who pursued its bounds, and whose lives reflected the values, principles, and the ethos of the West.

In his frail youth, Theodore Roosevelt would read the same “Leatherstocking Tales” as Hansen and be inspired to venture into the Western frontier.

Roosevelt wrote of his time as a ranch hand in the Dakota Territory, published in The Century Monthly Magazine as two articles richly illustrated by Frederic Remington’s etchings, “Frontier Types” and “In Cowboy-Land.” These formative experiences shaped Roosevelt’s worldview, reinforcing the romantic narrative of individualism, rugged determination, persistence, moral virtue, and quiet, humble strength that the Western Man represented.

It eventually endeared him to the people who would call him president. In this steeled masculinity, unbowed by fear yet made modest by nature’s unforgiving elements, he stood with the average worker, fought Big Business monopolies, celebrated and protected our natural resources for future generations, bestowed a love of American spirit and belief in its role as protector of freedom and liberty in the world.

Roosevelt wrote about the raw nature of the frontier, as powerful as the wind shaping the Arizona canyons, and bred hard men who “led hard lives”

They were — and — such of them as are left still are — frank, bold, and self-reliant to a degree. They fear neither man, brute, nor element. They are generous and hospitable; they stand loyally by their friends, and pursue their enemies with bitter and vindictive hatred. For the rest, they differ among themselves in their good and bad points even more markedly than do men in civilized life, for out on the border virtue and wickedness alike take on very pronounced colors.

The men who set out to tame the West, men like Roosevelt, might have discovered more than just an endless horizon that disappears beyond the waves of grassy plains or a sunset that drips golden hues between the mountain peaks and rocky valleys.

They discovered a nation that would do as much to shape the world as it shaped them; that this land would be as defiant and untamed in the eyes of the Old World as the men who were born of it. We can take the lessons of what historian Frederick Jackson Turner wrote in his seminal 1893 work, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady movement away from the influence of Europe, a steady growth of independence on American lines … that it lies at the hither edge of free land.

It is this formalistic character that separated the Old World from the new American West. Yet, every day we’re assured of our demise. The Old-World aesthetic was replaced by the stark brutalism of the Cold War brick-by-brick, gradually progressing into post-modernism, casting aside outdated mores in favor of the emergence of technological, asexual authoritarianism that reached a crescendo in the post-Trump era.

What was at best an apathy towards, or resentment of American leadership has taken a condemning turn as the shrill insistence of America’s self-destruction grows louder. It is a clarion call that forms an unlikely alliance between Americans whose self-loathing is exuded by the leftists who worship at the altar of America’s original sin, and a certain corner of the conservative right who see an irredeemable decadence escapable only through models of European and Eurasian societal authority of places such as Viktor Orbán’s Hungary or even Xi Jinping’s China. Where they inevitably converge is at the intersection of an aristocracy antithetical to the very nature of America’s being, not just its self-image.

In an interview published on April 2 in The New Statesman, Bruno Maçães asks former Russian presidential advisor and chair of Moscow’s Council for Foreign Defense Policy Sergey Karaganov, “Do you sometimes fear this could be the rebirth of Western power and American power; that the Ukraine war could be a moment of renewal for the American empire?” Karaganov responds in the negative, asserting his belief this moment is one in a pattern of decline.

So the West will never recuperate, but it doesn’t matter if it dies: Western civilisation has brought all of us great benefits, but now people like myself and others are questioning the moral foundation of Western civilisation.

I think geopolitically the West will experience ups and downs. Maybe the shocks we are experiencing could bring back the better qualities of Western civilisation, and we will again see people like Roosevelt, Churchill, Adenauer, de Gaulle and Brandt back in office. But continuous shocks will of course also mean that democracy in its present form in most European countries will not survive, because under circumstances of great tension, democracies always wither away or become autocratic. These changes are inevitable.

Our current situation resembles a not-too-distant past. A proper understanding of our contextual existence and more importantly our responsibility in the world is important. America needs to fully embrace a disposition shaped by the frontier and the cowboy ethos that is shunned by an elitist aristocracy that hates it and cheers for its destruction even as it enjoys the liberty and wealth of its past sacrifices and its present stubbornness provide.

America is perpetually never far from an existential moment of choice. But it is important to acknowledge that we do have a choice: to listen to the seething naysayers who would rather live in a world of cruel despots who shine fleeting favor on them, or to shrug off the burden of its own self-doubt, being the reluctant hero that never really conquers the frontier, but is shaped by it, existing in a world of wild beasts, harsh elements, barbed wire, and the barrel of a gun.

The frontier created the living myth we should not only defend but hold up as our ideal, a high moral bar that few can master and most don’t attempt. As Cooper wrote to his friend, inventor Samuel Morse, “We should assume the frank attitude of the republicanism we profess, ask only what is right, and take nothing less.”

America thrives when it embraces its role as a morally confident outsider, the one captured in Hansen’s and Remington’s art, in Cooper’s tales, and in Roosevelt’s words. The America of the frontier — and it is not dead yet.

This essay was first published in “A Pilgrim’s Progress.”