The Senate currently finds itself in the unusual situation of a tie – evenly split between 50 Democrats and 50 Republicans. As a procedural matter, a Senate tie requires some interesting maneuvering. A power-sharing agreement must be passed to hammer out how the majority-minority dynamics will play out. Also, in theory, the vice president must be on notice to break any tie votes that occur – something that would be happening a lot more if so many Republicans weren’t happily voting for so many of Joe Biden’s nominees.

But a tied Senate also creates opportunities. As I’ve written previously, the Senate’s Rule 26 comes into play in a tied Senate in a way that would hardly matter otherwise. The rule requires that a “majority of the committee” be “physically present” to report a matter (either a bill or a nomination) out of committee. This is true regardless of what an individual committee’s rules say about minority members being present.

Normally, a single party can present a physical majority of members because the committee makeup reflects how the Senate is constituted. But in a tied Senate, the committee ratios are also tied – meaning that if one party denies a quorum (that is, fails to show up), the committee cannot report matters to the floor of the Senate. A physical majority of members is not present. The bill or the nomination is stuck.

This is how the Senate Judiciary Committee could block Biden’s nominee to the Supreme Court from reaching the Senate floor. But it also applies in every other committee. Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., and Small Business Committee Republicans have been using this strategy for months to hold up the confirmation of deputy administrator of the Small Business Administration over illegally disbursed Covid relief funds to Planned Parenthood.

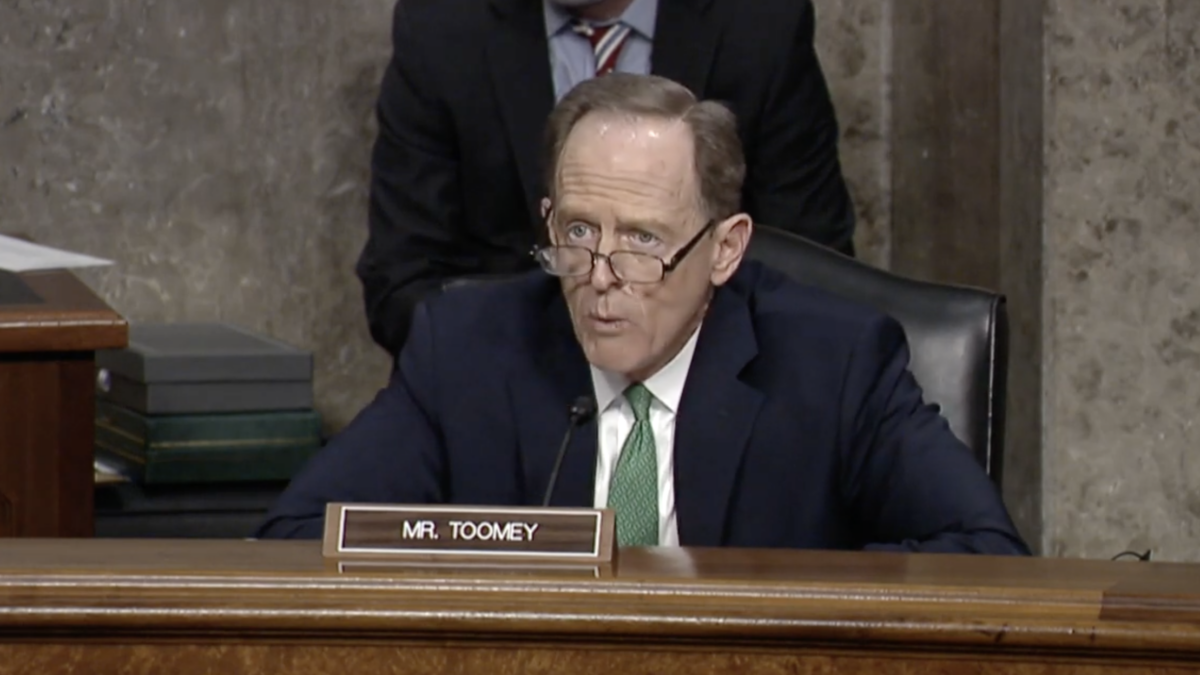

Most recently, Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Penn., and the Banking Committee Republicans denied a quorum in order to prevent the committee from reporting out the nomination of Sarah Bloom Raskin to the Federal Reserve.

Raskin’s Revolving Door

Senate Republicans are primarily interested in Raskin’s lack of clarity in answers to committee questions related to revolving door issues, particularly how she used her influence following her tenure at the Federal Reserve and the Department of Treasury during the Obama years.

After leaving Treasury in 2017, Raskin joined the board of directors of the Reserve Trust Company, a financial technology (fintech) firm which provides payment processing and other services for business-to-business payment companies. While there, Raskin appeared to use her connections at the Fed to help secure Reserve Trust a Federal Reserve master account, making them the only nonbank fintech company to have access to the Fed payment system.

Raskin not only appeared to help Reserve Trust secure the coveted status, which gives fintech companies direct access to Federal Reserve clearing, payment, and settlement systems, she did so by helping overturn the denial of their initial application. Several applications for fintech companies were either stalled or denied at the Fed, seemingly due to Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s hesitancy about granting access to these firms. Reserve Trust was initially denied its application – until Raskin intervened.

The master account designation later led Reserve Trust to receive more than $30 million in venture capital funds from QED investors – a fund led by Raskin’s former Treasury Department colleague, Amais Gerety. Following the infusion, Raskin cashed in her shares of Reserve Trust for close to $1.5 million.

Yet, when pressed, Raskin told the Senate Banking Committee she didn’t know why Reserve Trust wanted a master account, and reportedly couldn’t recall querying the Kansas City Fed on their behalf, even though the Kansas City Fed confirmed that a call on the matter did indeed take place.

There remain other outstanding issues with Raskin’s nomination, particularly her previous engagement in campaigns to use the Federal Reserve to pressure banks into choking off credit to traditional energy companies. This, as U.S. energy prices soar, the Russia-Ukraine conflict threatens U.S. crude sources and we remain overly reliant on international sources of energy. Considered in this light, Raskin’s nomination not only has ethical concerns but serious domestic policy problems as well.

Senate Banking Committee Republicans have since submitted follow-up questions to Raskin about her role at Reserve Trust. Raskin has refused to answer, choosing instead to respond to written questions submitted by the committee claiming she could “not recall” or “was unaware” no fewer than 36 times.

Republicans Find Their Leverage

As a result, the Banking Committee Republicans have simply used the Senate rules to their advantage. In failing to provide a quorum, the conditions of Rule 26 (which supersedes any committee rule) make it impossible for Raskin’s nomination to move forward.

Ironically, the same tactic was tried by Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, now Banking Committee chairman, in the Senate Finance Committee in 2017 over Trump Treasury nominee Steven Mnuchin and Health and Human Services nominee Tom Price. Brown and his Finance Committee colleagues led a boycott on the nominees, holding a press conference down the hall from where the vote was taking place. The concerns they felt justified the boycott were the same as what Republicans are taking issue with now: unanswered questions about the nominees’ business dealings.

Ultimately their gambit failed because, regardless of committee rules that require participation of the minority, Rule 26 only requires that a physical majority be present to vote out a matter, regardless of party affiliation. Republicans, who then held a clear Senate majority, were able to provide that. (It’s the same reason Sen. Lindsay Graham was able to overcome a Democratic boycott of Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court.)

But what doomed Democrat efforts in 2017 and 2020 is what makes Republican efforts in 2022 successful. A tied Senate (and the corresponding tied committee membership) prevents a physical majority from being present, and keeps the nominee bottled up in committee.

Toomey and his members have made clear that, while they wildly disagree with Raskin’s ideology on climate change, their blockade of the nomination is solely related to her refusal to answer their questions. “[O]ur actions to deny a quorum were not the result of Ms. Raskin’s radical public comments and beliefs about using federal financial supervisory power to advance climate change policy,” the senators wrote in a letter to President Biden. “Rather, it was the continual evasion and lack of candor about her time on the board of Reserve Trust.”

Republicans have also stated their willingness to report out the four remaining Federal Reserve nominees considered alongside Raskin. Committee Chairman Brown, however, refuses to separate them.

The Senate is a body of parliamentary equals, and this is especially true when the chamber is tied 50-50. A tied Senate gives Republicans a uniquely powerful position to express their will. Thus far Sens. Paul and Toomey, and the Republicans they lead on their respective committees, have been the only senators willing to use the leverage available to every Republican senator. Who will be next?