Should hospitals give special treatment to patients based on race? The people controlling your health care might think so. The concept of “health equity” is rising in hospitals, universities, and government health agencies.

Health equity’s premise is straightforward: with certain diseases, different races have different health outcomes. Health equity, inspired by critical race theory, dictates that any racial disparity in health or health care is proof of “structural racism” within the health-care system and society more broadly.

Health equity, according to Oregon’s Medicaid program, for example, means “disrupting” and “dismantling” structural (or systemic) racism to ensure equal health outcomes among all races. While eliminating racial disparities is a laudable goal, the chosen methods to impose health equity, in many cases, include intentional racial discrimination.

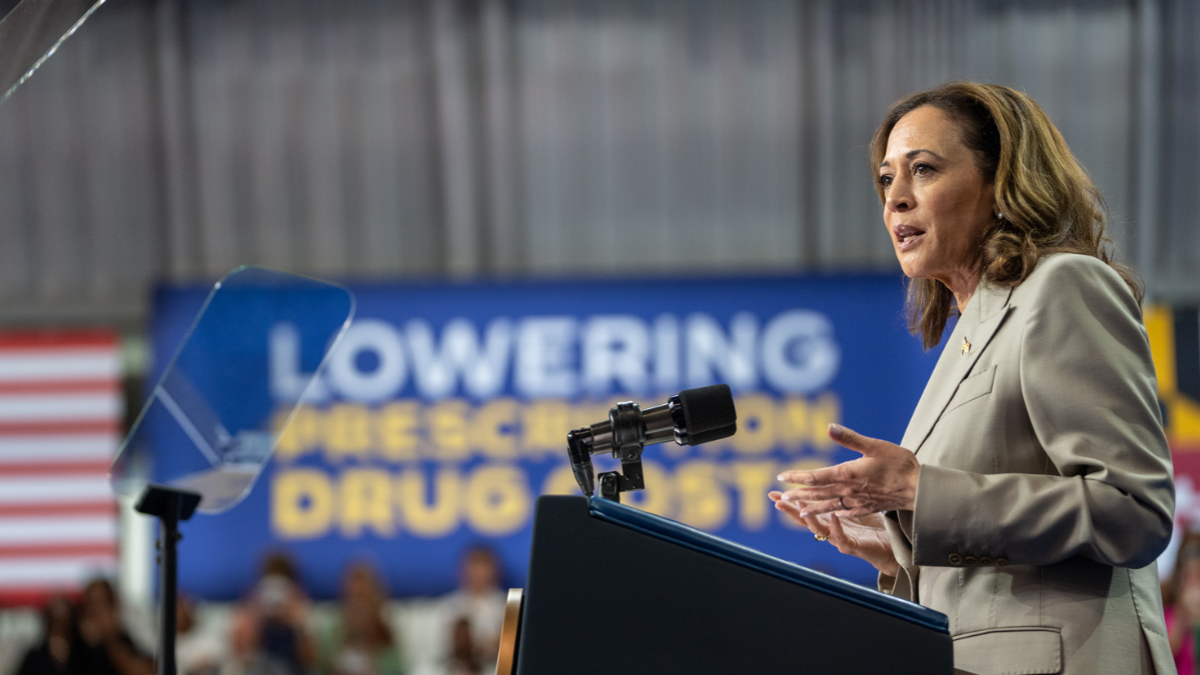

Here’s how it works in practice: medical experts identify a racial disparity. For example, certain minorities have an elevated risk of poor COVID-19 outcomes. According to the Minnesota Department of Health, this fact alone is evidence of systemic racial injustice and demands racial discrimination in the distribution of monoclonal antibodies (or “mAbs” — a medicine that fights COVID-19). In the name of health equity, Minnesota allocates mAbs based on race.

Specifically, Minnesota says that “race and ethnicity alone … may be considered in determining eligibility for mAbs,” and that non-white patients can be “prioritized for allocation of mAbs.” Minnesota is no outlier: other states add race into the calculus for life-saving treatments.

Utah, for example, similarly distributes mAbs based on a “risk score” under which “non-white” patients get bonus points in the calculation. Vermont, like several other states, has distributed vaccines based on race, and now plans to do the same with boosters.

Race-based health care is not limited to COVID-19. In Boston, two physicians from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Bram Wispelwey and Michelle Morse, recently called for “An Antiracist Agenda for Medicine.” These doctors reject “colorblind solutions” for health care, and instead advocate for “race-explicit interventions.”

Wispelwey and Morse aim to solve racial disparities in heart failure management. In a new pilot project, physicians “center Black and Latinx patients” by giving “a preferential admission option for Black and Latinx heart failure patients to our special cardiology service.” If you are white, you don’t get the special treatment.

At the University of Wisconsin, multiple mental health providers are assigned exclusively to non-white students. In a press release on September 9, 2021, UW officials announced they have assigned at least three, and perhaps as many as 11, mental health providers to “exclusively serve students of color.” If you’re white, you don’t get to see these counselors. The Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty (WILL), where I serve as deputy counsel, recently demanded that UW abandon this policy of segregated medicine. In response, UW backtracked, claiming that they were no longer providing segregated health care.

The problem with all of this is that much of American law is premised on the principle of equality, not equity. While racial disparities warrant investigation and intentional racial discrimination should be eliminated everywhere, citizens seeking health care must be treated equally as individuals based on their unique medical needs, regardless of the color of their skin.

Hospitals, doctors, and universities, whether public or private, that reject equality and instead group patients in racial categories should run headlong into our legal system if they persist in differing treatment based on race. In situations involving government actors, like state universities and health agencies, the U.S. Constitution guarantees equality under the law.

Under the Constitution, race-based government decision-making is categorically prohibited unless narrowly tailored to serve a government interest. This is an exceedingly high bar and has rarely been met outside the limited category of the school desegregation cases.

Private health-care providers, nearly all of which accept federal money in the form of Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal programs, are subject to the Affordable Care Act, which mandates that patients may not be treated differently based on race. Even apart from these legal constraints, we should ask ourselves as a nation: is racial discrimination ever moral?

People should be treated as the individual human souls that they are, not as generalized stereotypes. Specifically in the context of health care, patients should be treated individually, based on their personal symptoms, individual risks, and health history, not as members of a racial group. Discrimination-based “health equity” is not health care — it is simply social engineering masquerading as “science.”