When Wallace Willis created his mournful song, “Steal Away to Jesus,” he voiced his suffering in slavery with a lament that has evoked a powerful response through the ages and across the world. “Steal Away” has touched poets, presidents, queens, composers, and blind street musicians.

The song speaks to brokenness and sorrow across ages. It has spoken to a blind street singer in Macon, Georgia in the 1950s trying to make a living singing “slave songs” with a collection cup tacked to his guitar, and to an English composer who heard in it the suffering of the Nazi pogroms against Jews in World War II.

It has been sung around the world, from the inimitable Mahalia Jackson’s soul-stirring rendition with Nat King Cole in the 1958 movie “St. Louis Blues” to the moving concert presentation by college students with the National Taiwan University Chorus of noted composer Moses Hogan’s arrangement.

Steal Away, Steal Away, Steal Away to Jesus

Steal Away Home, I ain’t got long to stay hereMy Lord calls me, he calls me by the thunder.

The trumpet sounds withina my soul. I ain’t got long to stay here.

“Steal Away” pairs the pathos of backbreaking, heart-crushing slavery – the startling realization that a slave has to “steal” himself away from his slaveowners to be free – with the liberating promise of ultimate deliverance in Jesus. It recalls the Israelites’ “fear and trembling” as Moses received the Ten Commandments, in addition to the glorious resurrection when the Lord sounds his trumpet.

Renowned poet James Weldon Johnson praised the song in the preface to the collection of American African-American spirituals he and his brother published in 1925.

“Consider the sheer magic of…Steal Away to Jesus….and confess that none but an artistically endowed people have evoked it,” he wrote. “From whom did these songs spring – these songs unsurpassed among the folk songs of the world and in the poignancy of their beauty, unequaled?”

Unlike most spirituals written by “unknown black bards,” we know the writer of this sacred spiritual and something of his earthly journey. Before 1830, Wallace Willis and his wife Minerva worked on the cotton plantations of Britt Willis, a wealthy part-Irish part-Choctaw slaveowner in Holly Springs, Mississippi.

Around 1831, Wallace and Minerva joined the 300 other slaves of the Willis plantation to walk the grueling 400-mile Trail of Tears to Oklahoma when the Choctaws were expelled from Mississippi. Surely the deep soul-stirring “Steal Away” captured their feelings on the harrowing journey – not to freedom, but to slavery in another land.

My Lord, He calls me, He calls me by the lightning;

The trumpet sounds within my soul;

I ain’t got long to stay here.

Some scholars believe “Steal Away” was a coded song to help slaves escape to freedom. “In the spiritual, people are not only told to ‘steal away’ to Jesus, but also to run away,” notes Dr. Raymond Dobard, professor of art and art history at Howard University.

Wallace and Minerva worked sunup to sundown in blistering cotton fields along the Red River. In the “off” season, Britt Willis sent the couple to work at Spencer Academy, a boarding school run by the Choctaw nation to teach their youth.

The students loved them because of the songs they sang while working and in evening programs. So did Rev. Alexander Reid, an abolitionist Scottish preacher and school superintendent, who wanted to preserve the songs by helping Wallace write the words and memorizing the melodies.

“My grandfather, Uncle Wallace, was a slave of the Wright fam’ly when dey lived near Doaksville, and he and my grandmother would pass de time by singing while dey toiled away in de cotton fields,” Wallace’s grandson remembered in the Works Progress Administration Oklahoma Slave Narratives. “Grandfather was a sweet singer. He made up songs and sung ‘em. He made up ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’ and ‘Steal Away to Jesus.’ He made up lots more’n dem, but a Mr. Reid, a white man, liked dem ones de best and he could play music and he helped grandfather to keep dese two songs. I loves to hear ‘em.”

Wallace and Minerva were freed by the 1866 Reconstruction Treaty and settled near Doaksville, Oklahoma. Most historians believe they were buried in unmarked graves in the slave cemetery there, never knowing how Wallace’s songs lived on – crossing the ocean, traveling the world.

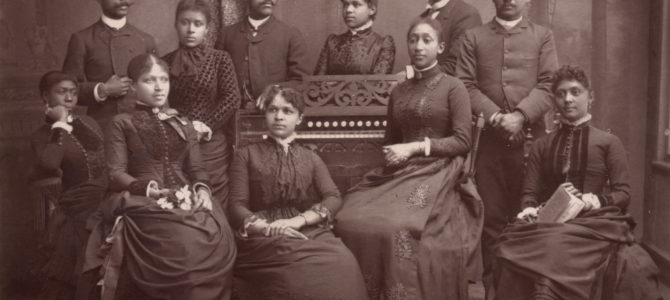

Reid shared the songs with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who added “Steal Away” to their repertoire. In 1872, the Jubilee Singers were invited to the White House to sing spirituals – including “Steal Away” – for President Ulysses Grant. The following year, they crossed the ocean and sang for Queen Victoria.

The queen specifically requested the Jubilee Singers to sing “Steal Away.” “Her voice was very low pitched,” recalled singer Maggie Porter, “but we heard her.”

Years later, in 1939, England had just entered World War II and composer Michael Tippett was looking for music to express the depth of emotion he felt in composing his secular oratorio, “A Child of Our Own,” about the horror of Kristallnacht in November 1938.

By sheer chance, he heard a radio program broadcast the spiritual “Steal Away.” He was struck by the power of the words “The trumpet sounds within-a my soul,” and recognized the potential for slave songs to speak to audiences in other parts of the world.

Tippett wrote to America for a collection of spirituals, and chose five: “Steal Away,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See,” “Go Down, Moses,” and “O By and By and Deep River.” His haunting arrangement of “Steal Away” includes a soft sorrowful soprano descant that seems to float above the world. His best-known work, “A Child of Our Time,” first premiered in London in 1944 and has since been performed all over the world.

These “arrangements of five African-American spirituals universalized expressions of suffering and hope,” says Oliver Soden, author of “Michael Tippett: The Biography.” Tippett “was thrilled by the way in which it spoke, as it continues to speak, for the oppressed of the world, and he wept when, during performances in the southern states of America in the sixties and seventies, the audience quietly joined in with the spirituals.”

Pearly Brown, born blind in Wilcox County, Georgia, grew up hearing his grandmother – who had been a slave – sing what he called the “slave songs.” His recording of “Steal Away,” with his plaintive voice strumming a single guitar chord, seems to come straight from those cotton fields in which his grandmother suffered.

Another interpretation showing the strength of the song and its meaning to African American music is offered as “Ain’t Got Long” by Mighty Clouds of Joy in 1964 at the Jubilee Showcase, the television show that featured all the top gospel groups and aired on ABC’s Chicago affiliate television station, WLS Channel 7, from 1963 to 1984.

These heart-rending “slave songs” are a gift to the world, as James Weldon Johnson writes in his commemorative poem, “O Black and Unknown Bards”:

O black and unknown bards of long ago,

How came your lips to touch the sacred fire?

How, in your darkness, did you come to know

The power and beauty of the minstrel’s lyre?

Who first from midst his bonds lifted his eyes?

Who first from out the still watch, lone and long,

Feeling the ancient faith of prophets rise

Within his dark-kept soul, burst into song?Heart of what slave poured out such melody

As “Steal away to Jesus”? On its strains

His spirit must have nightly floated free,

Though still about his hands he felt his chains…