“The next few years will be ghastly,” wrote C.S. Lewis in September 1939, just two weeks after Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

Although a man of faith, Lewis confessed to a friend that his nerves were “often staggered” by the news from week to week. A combat veteran of World War I, Lewis described “the ghostly feeling that it has all happened before.”

Writing at about the same time, an Oxford University colleague, J.R.R. Tolkien, explained to his publisher that “the anxieties and troubles that all share,” coupled with new responsibilities in “this bewildered university,” had made him “unpardonably neglectful” of his efforts to finish his sequel to “The Hobbit.”

Even if 2020 goes down as the year of the pandemic, the year that everyone wanted to forget, it also brought a cure as we forge through 2021: The next few months may be ghastly until it fully arrives, but there is a distant light in the night sky.

There were not many bright spots in the years 1939-1945 when it seemed that not only Great Britain but Western civilization itself sat on the edge of a knife. Yet these years proved to be among the most creative and meaningful for two of the 20th century’s greatest Christian authors. Indeed, those uncertain times were the crucible for a friendship that helped to ignite their astonishing literary imagination.

The war that brought unspeakable suffering also contributed to the creation of some of the most beloved and heroic literature of modern times. Gloom and defeatism were the order of the day. From the moment Great Britain declared war on Germany, the military situation went from bad to worse. Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, France — all collapsed before the German blitzkrieg.

Within days after becoming prime minister, Winston Churchill was forced to evacuate 338,000 British and French troops at Dunkirk, what he called “a colossal military disaster.” All of Britain braced for an invasion as Adolf Hitler sent his bombers to destroy London.

‘Between Wolves and the Wall’

Although Oxford was mostly spared from air attacks, the war still touched close to home. Tolkien and Lewis served in the home guard; both had family members in harm’s way. Tolkien’s son, Michael, served as an anti-aircraft gunner during the Battle of Britain. Tolkien wrote to him in January 1941: “Hitler must attack this country direct and very heavily soon, and before the summer … God bless you, my dear son. I pray for you constantly.”

Lewis’s brother, Warren, also a WWI veteran, was recalled and sent to France: “a sad business for us both,” Lewis wrote to a friend, “since he was retired and we had both hoped these partings were over.”

Despite these anxieties, both authors entered a season of intense creativity. Tolkien had begun writing “The Lord of the Rings” in 1937, shortly after “The Hobbit” was published. But the story languished for months. He picked it up again in earnest in late August 1940, at the start of the Blitz on London.

Over the next several months, Tolkien brought the story as far as “the mines of Moria.” Due to wartime shortages, his writing was done on the blank side of student examination paper. At Moria, the Fellowship found itself divided over whether to venture forward into the blackness: “All choices seem ill, and to be caught between wolves and the wall the likeliest chance.”

Amid committee meetings, lectures, and tutorials, not to mention more than one bout with the flu, Tolkien pressed on with his “mad hobby.” He told his publisher in March 1945 that he could probably finish “The Lord of the Rings” in three weeks if he had adequate rest and sleep. However, he wrote, “I don’t see any hope of getting them.”

‘To Fill the Universe’

The idea for Lewis’s children’s series, “The Chronicles of Narnia,” probably entered his mind in 1939, soon after children evacuees came to live in his Oxford home. On the back of a manuscript, he scribbled what would become the opening lines of “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,” a story about four English children “when they were sent away from London during the war because of the air-raids. They were sent to the house of an old Professor.”

Lewis also conceived his diabolical satire, “The Screwtape Letters,” after he heard Hitler on the BBC, a speech simultaneously translated into English. The Nazi leader promised to deal mercifully with Britain when he conquered the island. “While the speech lasts,” Lewis wrote his brother, “it is impossible not to waver just a little.”

The next day, Sunday, July 21, 1940 — during a service in Holy Trinity Church, of all places — Lewis imagined a book consisting of letters between a senior devil, Screwtape, and his junior tempter, Wormwood. “He [God] really does want to fill the universe with a lot of loathsome little replicas of Himself,” lectures Screwtape. “Our war aim is a world in which our Father Below has drawn all other beings into himself.”

‘We Shall Have to Write Them Ourselves’

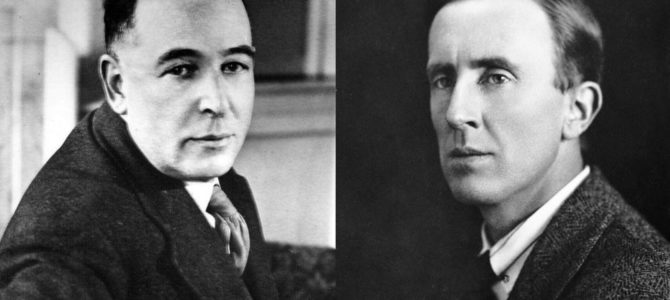

Tolkien and Lewis first met at Oxford in 1926, both instructors in English literature, and soon realized that they shared a love of ancient and epic mythology. One of the sources of their inspiration was, quite plainly, their friendship.

Lewis recalled a lively conversation in his college rooms about the gods and giants of Norse legend: “I was up till 2:30 on Monday, talking to the Anglo-Saxon professor Tolkien … Who could turn him out, for the fire was bright and the talk good.” They began meeting regularly to discuss their writings, joined by other authors who eventually formed “the Inklings.”

Tolkien and Lewis were deeply dissatisfied with the post-war literature of the 1920s and 30s, awash in themes of alienation and moral cynicism. The writings of authors such as Robert Graves (“Goodbye to All That”), Erich Remarque (“All Quiet on the Western Front”), and T.S. Eliot (“The Hollow Men”), captured the mood of disillusionment.

In “Modern Heroism,” literary critic Roger Sale wrote that World War I “was the single event most responsible for shaping the modern idea that heroism is dead.” The onset of another world war deepened this outlook but also stirred a sense of urgency in both authors. “If they won’t write the kinds of books we want to read,” Lewis announced to Tolkien, “we shall have to write them ourselves.”

That’s exactly what they did. Against the literary establishment, they reasserted the supreme importance of the individual in combating the evils of his age. They used the language of myth and fairy tale to communicate hard truths about the human condition. Like no other authors of their time, they retrieved the concept of the epic hero — and reinvented him for the modern mind.

Throughout the war years, Tolkien read each new chapter of “The Lord of the Rings” out loud to Lewis, who sometimes wept over the poignancy of a passage. “But for his interest and unceasing eagerness for more,” Tolkien later explained, “I should never have brought the ‘The Lord of the Rings’ to a conclusion.”

After Lewis read the finished manuscript, he described in a letter to Tolkien what it meant to him: “So much of your whole life, so much our joint life, so much of the war, so much that seemed to be slipping away … into the past, is now, in a sort made permanent.”

Perhaps Tolkien had his friend in mind when, in a scene from “The Lord of the Rings,” he expressed the power of friendship to help us discern, even in the darkest moments, flashes of grace and moral beauty. Frodo Baggins, frightfully aware of the forces threatening to defeat him in his quest to destroy the Ring of Power, is overcome with gratitude for the help others have given him. “Certainly, I have looked for no such friendship as you have shown,” he tells Faramir. “To have found it turns evil to great good.”

Here is a story of fellowship, of crisis and creativity, that can cheer our weary souls, whatever trials and sorrows this next year may bring.