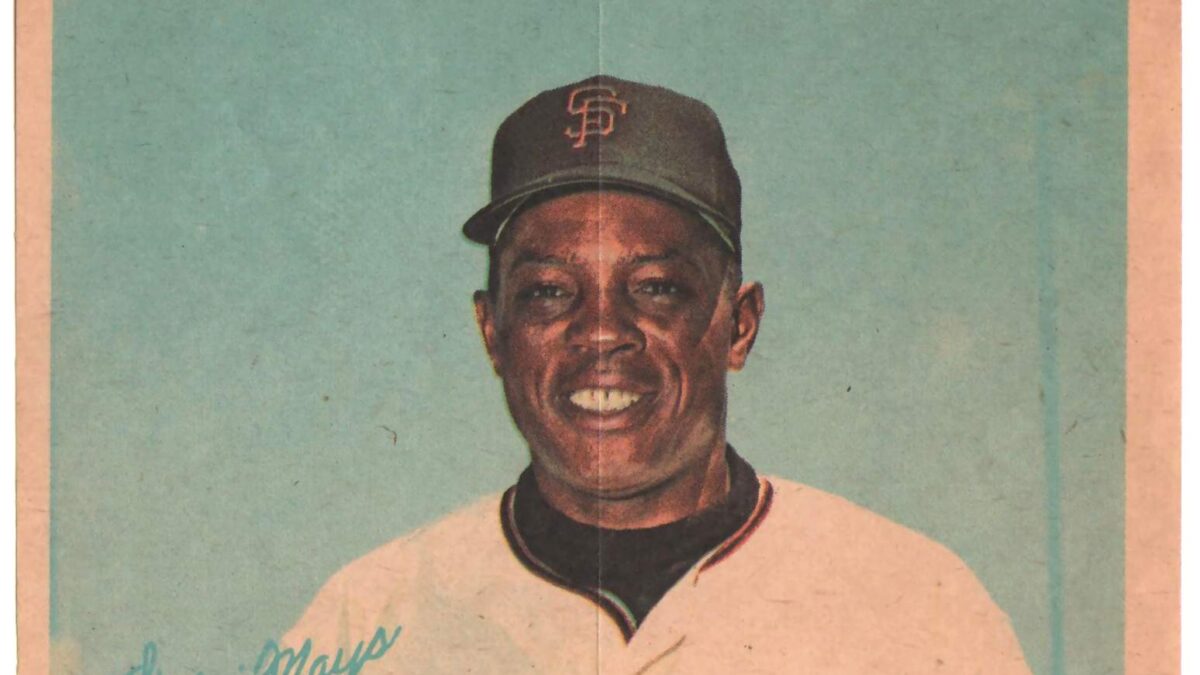

It seemed somehow fitting to read Tuesday’s announcement that the Baseball Writers Association of America failed to induct any new members to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2021. In addition to serving as confirmation of the tainted legacy of baseball’s steroid era, it also served as a backhanded tribute to one of the greatest players of all time: Henry Louis Aaron, who died last Friday at the age of 86.

During his seven-decade long association with the game, Hank Aaron served as a Hall of Famer in more ways than one. He stands in the pantheon of baseball legends for his prodigious achievements — not just as a player, but as a human being.

Stunning On-Field Accomplishments

Statistically, Aaron served as the model of consistency during 23 years in the majors, 21 with the Braves (first in Milwaukee, then in Atlanta) of the National League, and his final two with the American League’s Milwaukee Brewers. In that span from 1954 to 1976, Aaron hit 755 home runs, breaking Babe Ruth’s lifetime record.

Many individuals, including this one, still consider Aaron the true home run king. While major league records indicate Barry Bonds hit 762 home runs, questions surrounding Bonds and steroids mean many consider his “record” tainted.

Case in point: On Tuesday, Bonds received 61.8 percent in the Hall of Fame balloting, failing to qualify for the ninth straight year. By contrast, Aaron received 97.8 percent of votes cast in 1982 to qualify for the Hall on his first attempt.

But over and above one home run number, Aaron simply performed — day after day, year after year — in a way that gave him numerous baseball records:

- Most seasons with at least 30 home runs;

- Most career runs batted in;

- Most extra-base hits;

- Most career total bases;

- Third in hits, behind only Pete Rose and Ty Cobb.

The last statistic might surprise some individuals, who know Aaron only for his home run record. But he also won two National League batting titles, and held a .305 lifetime average, with 13 seasons above .300. His last season above .300 came in 1973, at the tender age of 39, when Aaron batted .301, with 40 home runs and 96 runs batted in — all while playing in only 120 of the Braves’ 162 games that year.

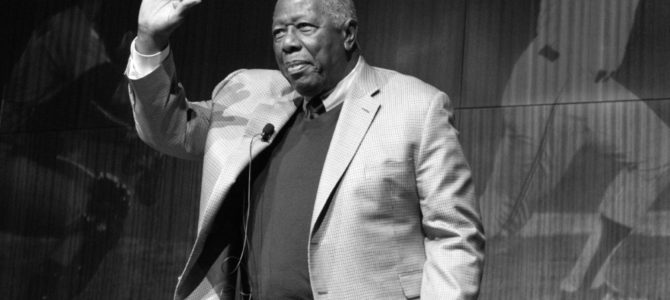

With Dignity and With Grace

Still, in many respects, Aaron’s on-field accomplishments pale in comparison to the example he set for all Americans. Because he broke Babe Ruth’s home run record, Aaron received a level of racist abuse and intolerance perhaps second only to that directed at Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s unwritten color barrier in 1947.

In 1952, Aaron briefly played for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues. By the 1970s, he had become the last active major leaguer with that historical distinction. Yet sadly, more than a quarter-century after Robinson reintegrated baseball, Aaron still faced many of the same racial prejudices as Robinson endured. Because he did not break the home run record during his impressive 1973 season — he ended that year just one shy of Ruth’s mark — he had to endure months of hate mail and threats during the offseason.

His 1990 memoir, “I Had a Hammer,” and Ken Burns’s multi-part series on baseball document the abuse Aaron faced — man’s inhumanity to man up close and personal. Having read the former during adolescence, I shudder to think how I would have performed under such circumstances, or whether I could ever move beyond — let alone forgive — people who held such hatred and enmity for no rational reason.

Yet, through it all, Aaron persevered. He hit home run No. 715 off Al Downing on April 8, 1974, eclipsing the great Ruth and establishing a new major league record. Following his retirement, he remained active in the baseball community, serving in executive roles for the Atlanta Braves and Major League Baseball.

A True Hall of Famer

Difficult as they are to define, legendary figures — Hall of Famers — might get summed up in four words: “I couldn’t do that.” Those words apply to Henry Aaron in multiple ways. By excelling on the field over more than a generation, he set new standards and records in America’s national pastime.

But just as most Americans could not dream of approaching Aaron’s on-field achievements, so too most Americans would find it difficult to move past the bigoted taunts and rhetoric he endured for much of his career. That Aaron did so stands as a testament to his character — an example of grace, healing, and reconciliation that we need as much now as we did during his playing days half a century ago.