Artist Rupert Alexander, who was featured in Vanity Fair earlier this year, first rose to international prominence back in 2010, thanks to his beautifully silver-toned, official portrait of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II.

As an artist whose paintings hang in public and private collections around the world, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, Alexander’s work is in great demand. So how does an acclaimed portrait painter try to do his job during a time of social distancing brought on by a pandemic? In an interview, I found out.

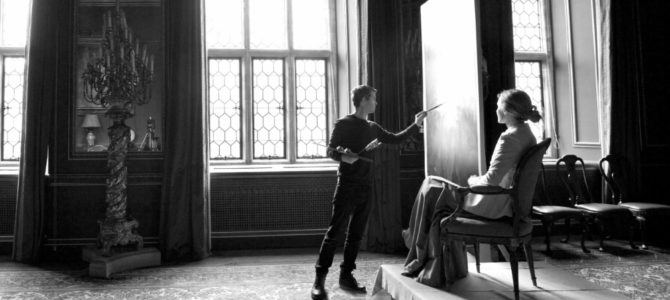

William Newton: You and your family recently moved from Central London to the countryside, and you inaugurated a new studio out there. For people who haven’t been inside a professional artist’s studio, could you describe what it’s like?

Rupert Alexander: Yes, we had been in London for 14 years and had long wanted to move to the countryside. We finally did so last year. While looking for a house to buy I started designing the studio, making sketches, and building cardboard models based on the design of the great nineteenth-century portrait studios.

By the time we moved to the new place — a pretty Georgian farmhouse — I had largely finalized the design. My drawings were turned into architectural schematics by a local firm, and building work began shortly thereafter. Much to my relief, within six months the studio was finished.

The studio comprises a large, double-height open space, the main feature of which is a 17- by 10-foot north-facing window. The window is rigged with various blinds and shutters that enable me to isolate any given section of the window so that the light can be adjusted to suit the structure of the sitter’s face or enhance the particular mood I’m trying to create.

It’s a wonderful, inspiring space, and is surrounded by beautiful rolling hills that are home to ancient monuments like Stonehenge and Avebury. I feel incredibly lucky to be working here.

WN: What would it have been like to try to keep working, if you were still living in the city?

RA: The lockdown has been felt less out here than in London. Moreover, in London, we lived in an apartment without a square inch of outdoor space, whereas here I can walk for an hour without seeing another soul!

That said, as an artist; I’m used to working alone between sittings, so a London lockdown wouldn’t necessarily have been more disruptive than it has been here. Far worse would have been a lockdown during the studio build. Had it happened last year I would have had nothing but a pile of bricks, and nowhere to work. I would have been making a very rapid transition to being a landscape painter.

WN: Being under quarantine must present challenges when your calling is that of a portrait painter, first and foremost. How have you managed to keep working while not being able to meet in person with your clients and sitters? I imagine that you feel some kinship with artists of the past, who had to execute portraits of patrons who lived far away and had only perhaps a few drawings, studies, and notes to go by when completing their work.

RA: At the outset of my career, and largely as a result of a very rigorous traditional training, I worked exclusively from life, with portrait sittings morning and afternoon. Fairly quickly though, such an inflexible approach became untenable as clients weren’t generally willing to sit for 50-plus hours! So the use of photography as an aide-memoire became a part of my routine.

During the lockdown, though, I’ve had to do away with sittings altogether, and have had to learn to paint exclusively from photos. Just before the government brought the shutters down, I took hundreds of photos of all my clients and have been using them to work on seven or eight portraits over the past few months.

Perhaps counterintuitively, it’s harder to paint from photos than from life. In my work, I try to convey as true a sense of life as possible, and photos stand as a barrier between the canvas and life itself. Representing three dimensions in a two-dimensional form is easier when working directly from three dimensions, as the human eye works very differently from a camera. Working from photos, one has to reverse engineer the third dimension.

Still, I’m lucky to have recourse to photography. When Bernini sculpted a bust of Charles I in his absence he only had Van Dyck’s three studies of the king to work from! By the late 19th century, painters were of course regularly using photography (there are works by Anders Zorn, for example, that are direct copies of photos that still exist).

But the Old Masters somehow managed to produce miraculous portraits of small children without the aid of photography. They had such a keen understanding of form that they could paint a moving target seemingly with little difficulty.

WN: I realize that every commission is different, but could you describe some of what goes into the process of creating a completed painting once you have your ideas down?

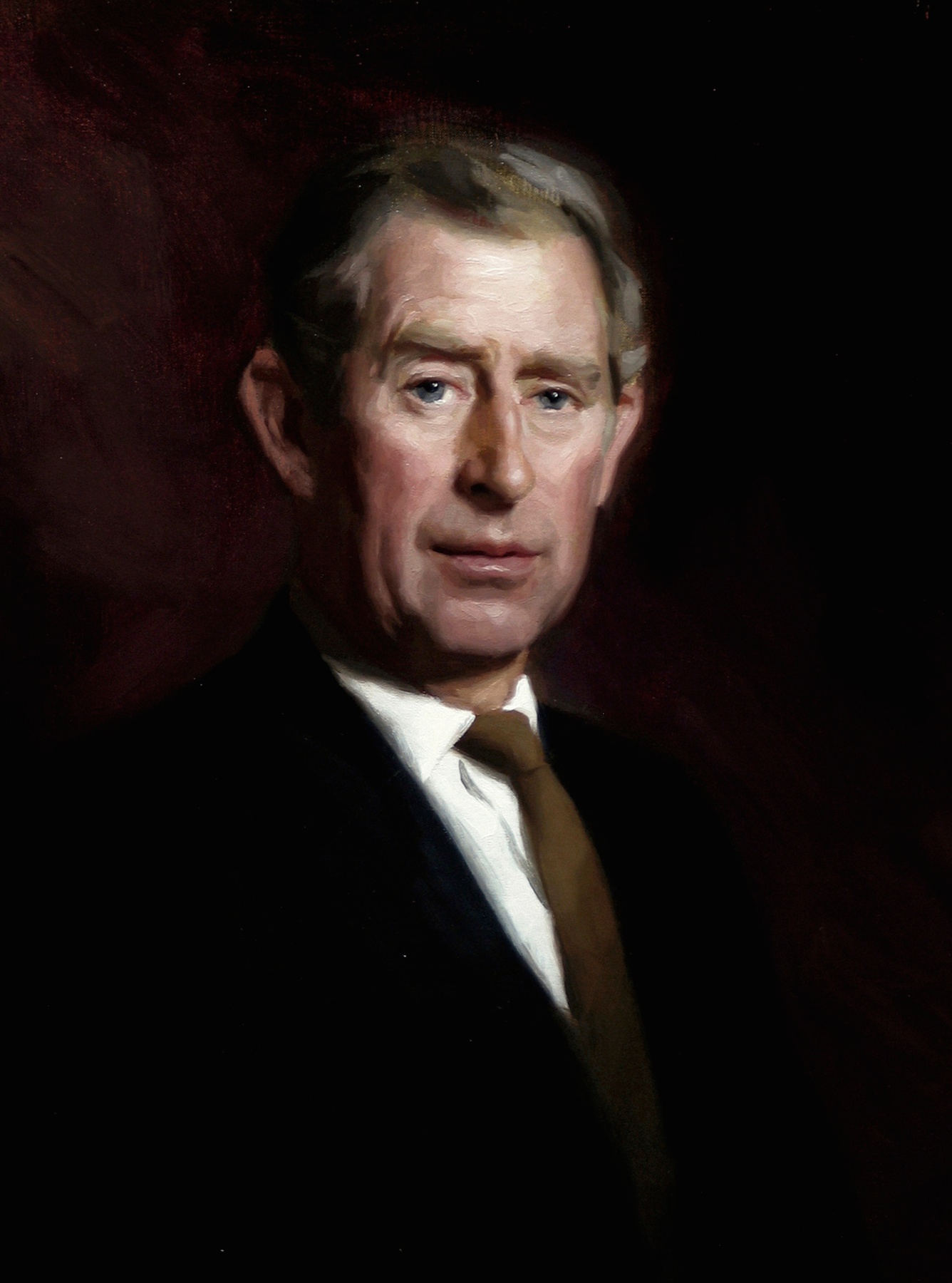

RA: Every portrait starts with a discussion with the client about the scale and scope of the work. Then at the first sitting, I start sketching compositional ideas, trying various poses and clothes, thinking about the illumination, and taking photos. For a larger painting, I might then make a color study of the final composition to work out the tonal arrangement, so that I’m not having to make major adjustments on the full-size canvas, which of course would be much more time-consuming. For a smaller canvas, I’ll jump straight into the final work.

My work usually involves three layers: the first to establish the proportions, gesture, and tone; the second to build up the impasto (thicker paint to increase the reflective quality of the surface, which enhances the sense of light); and the third to refine the form, color, and brushwork. Then it’s a matter of knowing when to stop. It’s said that it takes two people to produce a painting: the artist and then someone to shoot the artist before he ruins the painting…

WN: Are you having any difficulty at the moment in sourcing the materials that you use? I know that you create some of your pigments, for example, but are there any shortages of things like canvas, paint, varnish, and so forth, given how many businesses have had to shut down?

RA: No, I was stockpiling before it became fashionable! Some years ago I grew tired of my favorite art materials suddenly disappearing from production, so I started buying up large quantities of the linens, pigments, brushes, and oils that I favored.

Besides the main painting space, my favorite room in my new studio is the store, which is groaning with a lifetime’s supply of art materials. Oil paint tends to last for many years in the tube, so I haven’t been caught short there either, and at any rate, I make many of my paints myself, grinding pigments into cold-pressed linseed oil or poppy oil, depending on the pigment and the drying time I need.

WN: I’ve watched your work develop over the last decade or so, and from my perspective — you can correct me if you think I’m mistaken — while you continue working in a representational style, you’re also taking more chances with things like hues, posing your subjects, and brushwork. Do you feel that’s the case?

RA: I’m happy you feel that. I’m always exploring new ideas — in terms of technique, composition, mood, and so forth — and although the changes feel to me radical I sometimes wonder if they are apparent to anyone else!

Over the last few years, I’ve been commissioned to paint some large canvases that have provided the opportunity for greater experimentation. A recent portrait of a New York family, for example, provided enormous scope for compositional innovation that I had not previously had.

And I have started to explore ways to convey my ideas simply through light and color rather than a more literal use of props. For a portrait of the eminent mathematician Sir Andrew Wiles, painted for the National Portrait Gallery (London), I employed a cool, blue-green, ethereal light, redolent of the night, to suggest something of the cerebral world Sir Andrew’s inhabits.

WN: Other than the kinds of things we’re all looking forward to, like dining in restaurants or going to see a performance, what things have you missed that you can’t wait to get back to doing again?

RA: Quite honestly, taking my family to the beach! But yes, I can’t wait to walk through the doors of The National Gallery and spend some time in the Rembrandt room again. And as soon as the national borders are fully open I’ll be jumping on a plane to Madrid to reacquaint myself with the Velázquez collection at The Prado, or to New York to say hello to Sargent at The Met.

We are lucky, though, in the age of digital media, that we can keep abreast of what our peers are producing. Seeing the struggles and the triumphs of fellow artists around the world during the lockdown has been a source of solace and inspiration.

Artist’s Site::www.rupertalexander.com.