No more shall the war cry sever,

Or the winding rivers be red;

They banish our anger forever

When they laurel the graves of our dead!

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Love and tears for the Blue,

Tears and love for the Gray.

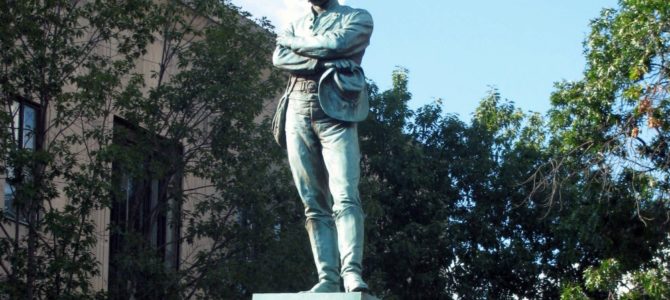

At the intersection of Prince and Washington Streets in Alexandria, Virginia, on a circular island amid the to-and-fro of D.C. commuters, atop a Richmond granite plinth, there stands the solitary figure of a man.

His hatless head inclines slightly. His gaze is downcast. His shoulders and mustache sag wearily. His arms, folded in resignation across his chest.

His boots and uniform are worn but not tattered. The passage of time has lent his bronze complexion a greenish patina. The artist has captured him in a moment of defeat and disillusionment—but also of defiance. Turning his back on Washington’s obelisk seven miles distant across the Potomac, he looks away, away down south: to Dixie.

Now change all the verbs to their past tense. Stood. Inclined. Sagged. Were. Had lent. Looked. Per the reporting of the Washington Post as well as my own two eyes, on Tuesday, June 2, the Alexandria Confederate Memorial (also known as “Appomattox”) was carted away to an as-yet-undisclosed location. The act represented the culmination of a multiyear crusade to remove a work of art for all the usual, tired reasons that need no rehearsal here.

The removal of a statue—even by a ravening mob—can, in a certain context, be exhilarating. Think of the toppling of Felix Dzerzhinsky from the square in front of the Lubyanka and his subsequent relocation to Moscow’s ghoulish Park of Fallen Monuments. Or, remember the crowds in Baghdad tearing down the grotesque effigy of Saddam Hussein. By contrast, here in Alexandria, a work of art was hoisted by the pitilessly bureaucratic jaws of a crane, perhaps to be “recontextualized” someday. And so a bit more of the decent drapery of city life is torn away.

Now the litany of caveats: This necessarily anonymous lament is not a brief for Confederate memorials, let alone for the Confederacy itself or its various symbols. I do not hold with secessionism or slavery. I am a Yankee—born and bred. I attended Civil War reenactments as a boy, always wearing blue, and once carried a Federal flag across a pretend battlefield. You would not see me shed a tear if Jefferson Davis Highway were renamed for a non-traitor.

“Appomattox” deserves at least one obituary, however, so here it is.

A Tribute to Those Who Died

The Alexandria Confederate Memorial was erected on May 24, 1889 “to the memory of the Confederate dead of Alexandria, VA by their surviving comrades.” An inscription on the plinth—which still stands as of this writing—adds that the monument “marks the spot from which the Alexandria troops left to join the Confederate forces on May 24, 1861.” Or were evacuated, rather. The men were in flight from the advance of Federal troops who had been ordered by Abraham Lincoln to invest the city within hours of Virginia’s declaration of secession. The occupation that began that day continued for the balance of the war.

On the monument are inscribed the names of 99 soldiers of the 17th Virginia Regiment who never returned to Old Town, having “died in the consciousness of duty faithfully performed.” Among them were three printers, two merchants, two molders, two plaisters, two students, a lawyer, a tinner, and even a “huckster,” as well as fourteen men of unknown occupation. Butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers all, “that for a fantasy and trick of fame / [went] to their graves like beds.” A report prepared by the Alexandria Library in 1988 estimates that no more than eight of the men appearing on the memorial ever owned a slave.

Their names are joined by that of James W. Jackson, an irascible local hotelier, rabid secessionist, and slaveholder. By all contemporary accounts, he was an ugly man.

On the day of the Union troops’ arrival, Jackson was the proprietor of the Marshall House on King Street, still today Alexandria’s main commercial thoroughfare. Upon entering the city, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, Lincoln’s friend and former law clerk, spied a conspicuous secessionist flag flying from a forty-foot pole mounted on the hotel roof—allegedly visible to Mary Todd Lincoln from the White House across the Potomac.

Joined by four of his 11th New York Volunteers, Ellsworth entered the hotel to remove the flag. Having secured it, Ellsworth descended to the lobby, where he was immediately shot and killed at close range by Jackson. Jackson himself was dispatched moments later by one of Ellsworth’s men. A well-circulated Currier and Ives engraving depicts the event as something of a Mexican standoff gone awry.

With his death, Ellsworth earned the distinction of first Union officer felled in the war. For his part, a commemorative plaque at the site—quietly removed a few years ago—declared Jackson “the first Martyr to the cause of Southern Independence.” The first fatalities of Alexandria’s war thus resulted from a symbolic scrum over a Confederate flag. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Bowed in Deep Contemplation

Like many Civil War monuments, the Confederate Memorial was conceived and commissioned by the little platoons of civil society, in this case, the members of the Robert E. Lee Camp #2 of the United Confederate Veterans. Funding for the statue and preparation of the site was raised in part through a communal bazaar. The ladies of Alexandria were particularly exhorted “to send us fancy articles which they know so well will attract and be saleable and contribute so largely to success.” The funds duly raised; a contest was held to select a design.

The unanimous choice, at an estimated cost of $3,500, was the entry submitted by John Adams Elder (1833-1895), whose plaster model was based on his 1888 painting, “Appomattox,” today on display at the Library of Virginia in Richmond. A native of Fredericksburg, Elder studied under Daniel Huntington in New York and then later Emanuel Leutze, renowned painter of “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” in Düsseldorf.

Elder enlisted in the Confederate Army on December 12, 1862, the day after the federal shelling of Fredericksburg began. After the war, Elder earned a living producing popular portraits of Confederate luminaries, including Lee, Jackson, and Davis, at his Richmond studio. Coverage of Elder’s model in the Alexandria Gazette was breathless:

It represents a Confederate soldier as if viewing the field of strife after the surrender. He stands, dressed in the old familiar uniform of the Confederate private, with folded arms and head bowed forward as if in deep contemplation over the scenes, privation and hard-fought battles through which he had passed, all for a principle which he deemed sacred and righteous, and yet all apparently for nought.

Perhaps at the suggestion of Elder, Caspar Buberl (1834-1899), a German-speaking immigrant from Königsberg in what is now the Czech Republic—a veritable Bohemian artist—was selected to sculpt and cast Elder’s design. A prolific monumental sculptor whose works appear on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line, Buberl is best known for the 1,200-foot frieze adorning the façade of the former Pension Building, now the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C.

The unveiling of “Appomattox” was a joyful and non-sectional affair. The Gazette again: “The occasion far exceeded in the way of a parade or open-air meeting ever seen in Alexandria, the city from daybreak having put on its holiday attire. Folk gathered from all over the region, coming by boat and carriage and on foot.”

Veterans of the war—now old men—trooped in uniform. Facing their own impending deaths in warm beds and surrounded by children and grandchildren, these men spared a moment to remember the ones who never came home. And so did their former enemies: Union veterans also attended the ceremony en masse, having had the decency to pay their respects to erstwhile foes, now countrymen again. The Rev. Mr. G. H. Norton offered a prayer: ‘May the memories of our departed heroes inspire us with patriotic devotion and may all hatred and strife be buried in their graves.’

With malice toward none and charity for all, indeed.

An Opportunity to Learn

Posterity—namely, ourselves, neighbors in time and space—was on the minds of Alexandrians that day in selecting the placement of the statue. “It will be placed where it can be plainly seen from all points, and where it will stand not only a beautiful work of art but an education for future generations in the history of the struggle made by the South for her rights and independence.”

With deference to those who would seek to “recontextualize” the monument in some museum corner, the very grounds on which it stood for so long are imbued with the city’s collective memory.

The point at which the monument has been placed is conceded to be the most central and at the same time the most appropriate in the city. It was from this place that the Alexandria companies took their departure to join fortunes with their Southern brethren, and though several other localities had been suggested, the corner of Prince and Washington streets has ever been looked upon as the most suitable spot on which to place the memorial to the fallen heroes.

We have decided to reject that education, from which we might have profited. Governor Ralph Northam—who could perhaps stand for a little education in Virginia’s history himself—signed a bill in April that ultimately granted Alexandria’s petty city fathers their long-yearned “condemnation of memory.” Northam was abetted by recently elected Democratic majorities in both houses of the Virginia legislature.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy, who have long owned the site and statue, opted to remove the statue a month earlier than planned, apparently out of fear for the memorial’s bodily integrity amidst our present discontent.

“Appomattox” survived gasification, electrification, and asphaltization, a couple of car accidents in the 1920s and 1980s (the evidence of which remains visible on the plinth), segregation, desegregation, integration, industrialization, economic decline, and bourgeois renaissance in Old Town. In the end, it succumbed to unnatural causes in the name of sanctimony and vandalism.

Rest in peace, “Appomattox.”