Preparing for a hog hunt is like preparing for the end of the world. You need a reliable rifle and ammunition, of course, but you also need a bunch of other stuff—a sidearm, maps, binoculars, compass, flashlight, knife, raingear, boots, food and water, two-way radios. Once you’re all geared up, you can’t help but think that if the end came, you’d be ready.

The feeling is even more intense when you go hog hunting during a global pandemic. It might not be the apocalypse, but when it comes to buying guns and ammo—or toilet paper—it might as well be.

I know, because I recently went on a hog hunt in East Texas. Hunting feral hogs might not seem like an essential activity during coronavirus lockdowns, but here in Texas it is.

Or at least it isn’t banned. In his March 31 executive order, Gov. Greg Abbott made it clear that hunting and fishing are not prohibited so long as proper measures are taken to prevent the spread of the disease.

Some friends and I had been planning a hog hunt for months, long before the pandemic upended our lives, and as the appointed weekend neared, we decided that if the governor said we could go and the ranch owner still wanted us to come, then we’d throw some face masks and hand sanitizer in our packs and go kill some hogs. Even if we didn’t get any, it would at least get us out of the house to somewhere besides the grocery store and Home Depot.

Yes, People Hunt Feral Hogs

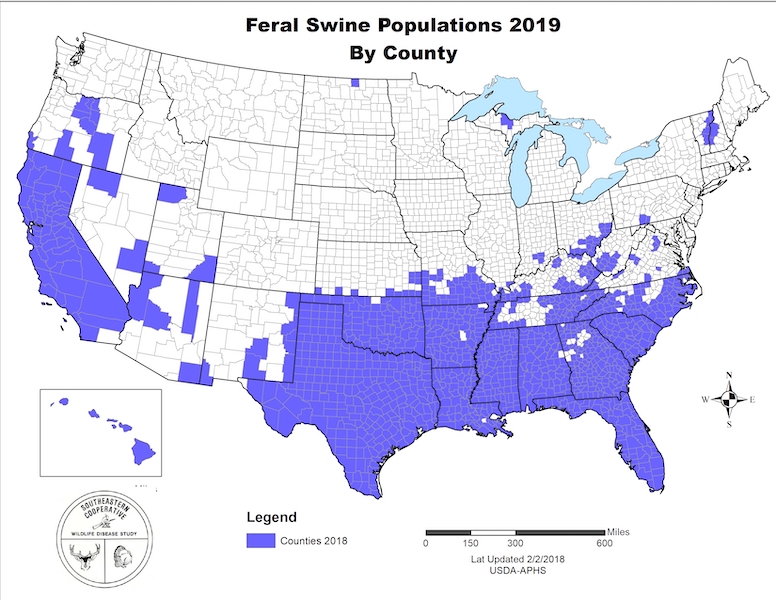

For the uninitiated, hog hunting is hugely popular across the South and especially Texas, which has the largest feral hog population in the country by far, some two million and counting (nationwide, there are between six and nine million feral hogs spread across 39 states).

Last summer, Texas lawmakers unanimously passed a law allowing anyone, resident or not, to hunt feral hogs on private land without a license, year round, with no limits. As far as the state is concerned, hunting feral hogs is pretty much like hunting rats or possums. If you see them, you can kill them.

If that seems harsh, understand that feral hogs aren’t domestic farm pigs. The term “feral hog” refers to hybrids of Eurasian wild boars (introduced to North America by Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century) and domesticated hogs that have escaped and gone feral. With the latter, they actually change physically, growing thick coats of hair and sharp tusks.

They’re an invasive, non-native wild species that’s incredibly destructive and sometimes dangerous. They tear up ranch land, destroy crops, infect livestock with diseases, eat endangered species, and on rare occasions will attack and kill people. In addition, they are incredibly intelligent and difficult to hunt or trap.

Many Americans have no awareness of this. Recall the “30-50 feral hogs” meme explosion that ensued when Willie McNabb, some random guy in southern Arkansas, responded to a tweet by musician Jason Isbell questioning the necessity of “assault weapons” in the wake of a mass shooting. “Legit question for rural Americans,” McNabb wrote, “How do I kill the 30-50 feral hogs that run into my yard within 3-5 mins while my small kids play?”

Legit question for rural Americans – How do I kill the 30-50 feral hogs that run into my yard within 3-5 mins while my small kids play?

— Willie McNabb 🐗 (@WillieMcNabb) August 4, 2019

Everyone on the internet had a good laugh at McNabb’s expense until some people pointed out that actually, feral hogs are a problem in rural America, can be very dangerous, and sometimes travel in herds of 30 or more. The Washington Post even ran an explainer-type piece about the affair.

Four months later, after everyone had forgotten about it, Christine Rollins, a 59-year-old caretaker for an elderly couple in rural east Texas, was killed by a large herd of feral hogs after she got out of her car, right in front of the couple’s home.

Attacks like that are rare, but property damage from feral hogs is commonplace. All told, they cause about $2 billion in property damage nationwide every year, an amount that’s steadily growing. In Texas alone the annual damage estimate is in the hundreds of millions, so there’s a powerful incentive for landowners to kill or trap as many as they can.

In recent years, they’ve begun outsourcing that killing to hunters, and in the process have managed to monetize the hog problem. Today, Texas hog hunting is its own little industry. Ranches all over the state offer almost every conceivable hog hunting experience, from traditional blind hunting, walking and stalking, night hunts with thermal and night vision optics, and for those willing to spend a couple thousand dollars—at least—helicopter hunts, including helicopter hunts with fully automatic rifles. There are even places that will take you hog hunting with a pack of trained dogs and a knife. (The dogs attack and pin the hog, and you come in with a knife and stab it in the heart.)

But no matter how many hogs are hunted down, it doesn’t make a dent in the population. Every year, hunters in Texas kill tens of thousands of the animals, but there’s no way to kill or trap them faster than they can reproduce. Females can begin breeding as young as six months old and produce two litters every 12 to 15 months, with an average of four to eight piglets per litter, or in the case of older sows, 10 to 13 piglets.

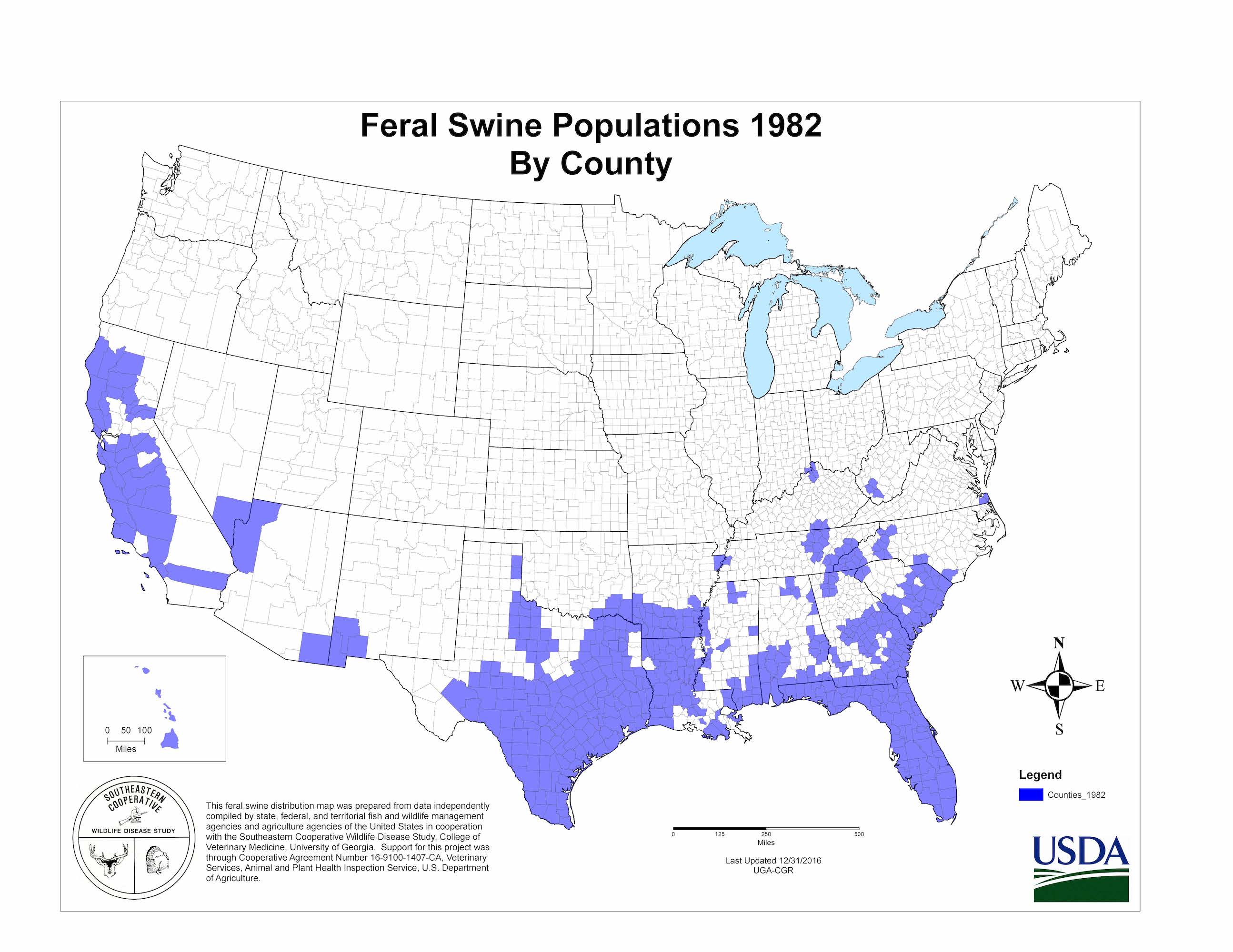

Hence, the population explosion of feral hogs over the past four decades:

Once primarily a rural problem, feral hogs are now becoming a problem in suburban areas. The federal government has even taken notice. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Agriculture created an office devoted to the wild hog problem, the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, which produced a 250-page report last year on mitigation efforts.

One idea that’s been kicked around for years is to poison the animals rather than hunting or trapping them. The trouble is, the poison ends up killing other wild animals besides hogs. In 2018, nearly 200 birds were found dead after Texas Parks and Wildlife researchers tested a new feral hog poison, forcing them back to the drawing board. For now, hunting and trapping are the only ways to stop feral hogs.

In Which We Try To Do Our Part

When we left Austin for our hog hunt, the city was under stay-at-home orders from the mayor. No one was really going out, except to the grocery store. The protests and public frustration over lockdowns that have recently bubbled up across the country hadn’t yet surfaced.

But as we drove east, conspicuous signs of the pandemic—face masks, social distancing lines at checkout—gradually receded. After we hit Bastrop, about 30 miles east of Austin, we turned northeast and headed for the small town of Crockett, situated between Dallas and Houston just west of Davy Crockett National Forest, the town’s namesake. Out in the small towns of rural east Texas, no one wore masks or gloves, there were no social distancing lines, and everyone seemed to be going about his usual business. In a gas station outside a place called Hearne, there wasn’t even any soap in the men’s bathroom.

We arrived at the ranch, a thousand acres of piney woodlands broken up by wide fields and grasslands, and were soon greeted by the owner, an elderly Texan with a thick drawl who told us he’d lived here on his family’s ranch his entire life. He showed us around, pointed out the half-dozen or so blinds and feeders, and left us to it. He said he didn’t mean to be “stand-offish,” but he was real worried about the coronavirus on account of his medical complications.

For all his concern about the coronavirus, he also told us that we were the first hunters he’d had out to the ranch in more than a month, and that he didn’t have anyone booked after us so if we wanted to stay a couple extra days, he’d offer us a real good deal. We told him we’d wait and see if we got some hogs.

Usually hog hunting is done at change-of-light, sunup and sundown, when the animals are active. And of course if you have night vision or thermal optics, you can hunt them at night. The species itself, sus scrofa, is not naturally nocturnal, but over the decades feral hogs have learned to be nocturnal as a way of avoiding hunters, so it’s rare to see groups of them moving about during the day.

But we did. The afternoon of the second day. we were making the rounds to the blinds we couldn’t cover that morning, checking for signs of feeding and activity. That’s when we spotted a group of about 20 hogs, adults and juveniles, walking across a grassy plain about 170 yards from us.

Hogs can’t see well, and they generally detect hunters by scent. We were downwind and they hadn’t detected us yet. There was nothing between us and them but a wide open field, no way to close the distance without risk of exposure. So we posted up on the fallen trunk of a massive oak and, hearts pounding, debated in hurried whispers who had the best shot as the herd made its way across the field in front of us.

My friends were both hunting with bolt-action rifles chambered in .308 Winchester, generally considered an ideal round for hog hunting (the .308 is one of the most popular big-game hunting cartridges in the world, similar to an M14 round, which the U.S. military used up until the late 1960s). I had an AR-15 chambered in .223 Remington, a much smaller round that requires precision to kill a hog—a head-shot, to be exact.

The AR-15, of course, is the “assault rifle” gun control activists always point to as an example of why we need stricter gun laws. In February, Joe Biden declared that no one needs a “weapon of war” like the AR-15, implying that its only conceivable purpose is to shoot as many people as possible in a short period of time. But there’s another conceivable purpose for such a gun: to shoot as many hogs as possible in a short period of time, and the AR-15 is perfectly suited for that purpose.

But not at 170 yards—at least not for a marksman of my skill level. I decided to let my companions take the first shots with their .308s, and I would follow up as best I could. They fired, the hogs broke into a run, I fired, and the whole thing was over in ten seconds. The three of us had fired a total of five rounds, none of us were confident we’d hit our marks. We set out across the field, hearts still pounding and weapons still at the ready in case a wounded or cornered hog decided to attack us, which they will sometimes do.

The first one we came upon was a wounded juvenile, about 60 pounds, at which no one had been aiming. We later surmised it must have been been hit by a bullet passing through one of the larger hogs. Still, a 60-pound juvenile makes for good eating, so we dispatched it and kept looking. We soon found the larger hog, a 165-pound sow, back in the woods about 15 yards, dead.

It’s hard to tell the size of a hog at 170 yards through a rifle scope, but we were pleased that we hadn’t shot one of the larger boars. If you plan to eat what you kill, which I always do, a 165-pounder is about as large a one as you’d ever want to shoot. The big boars are simply too tough, the meat too gamey to be any good. Even the juveniles need to be slow-cooked, which is what we did with the small hog that very night back at camp.

We butchered the sow and split it three ways, and now my freezer is full of frozen pork. That’s the best possible ending to any hog hunting trip, but especially a hog hunting trip during a pandemic.

For now, it looks like we might be over the worst of the coronavirus, that the spread of the disease is slowing, that stores and businesses will be opening up soon, that life might slowly be returning to normal. But if it doesn’t, I’ll be ready.