Tom Coburn didn’t want anyone to refer to him as Senator. He was Doctor Coburn. In a town built entirely around pomp and circumstance, where being one of the select 100, the most powerful individuals, who would endure beyond presidents and whose one word could block nominees and legislation was the highest goal you could achieve, Coburn believed it would be a step down to be a senator rather than a doctor.

In this, as in so many things, he was a permanent revolutionary, subversive and cantankerous, a follower of creeds and higher purposes and deep faith, who paid no mind to the expectations built into the field of politics. He existed in Washington, but walked through it as a man who lived apart from its values, a pilgrim in an unholy land.

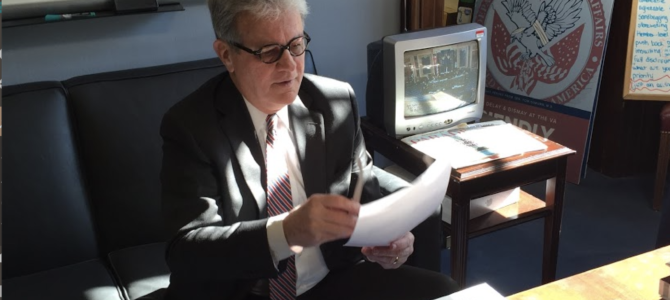

Coburn despised going native. Where many lawmakers allow themselves to be led around by the nose by staff who’d already spent a lifetime in Congress, the doctor hired young staff who hadn’t gone native or had the time to learn all the wrong lessons. He would teach them how to read bills and committee reports, tell them what he wanted them to accomplish, and then let them figure out the best way to make it happen. It sounds reasonable, but it’s not what senators do, not in the modern era at least.

Another thing they don’t do is care, really care, about dollars and cents. Coburn’s creation of the Wastebook marked a step that infuriated his fellow senators and turned the tide against earmarks – the Bridge to Nowhere just being one of the most prominent among them. Fiscal conservatism has no place in Washington these days, but that’s not a new thing. Here, demanding things be paid for and cuts be made to balance expenditures is an idea exclusive to a dangerous fringe. Coburn still believed in it, and his individual fights had outsized ramifications for the way the senate did its business.

You all know about the babies – the 4,000 or so he delivered while serving in Congress. What you might forget is how Congress tried to screw with him about it, knowing that it was his favorite thing to do. Coburn had a deal set up where he made no money to deliver babies – that any billing was break-even, and then when the Ethics Committee came after him, he shifted to billing nothing at all. They still tried to take it away from him. That’s how much he irritated everybody. A poll at the time showed the voters supported him, 77 to 8. He kept delivering babies anyway and told the senators to pound sand.

Roy Daniells has a poem about Noah that always reminded me of Coburn. “They gathered around and told him not to do it, They formed a committee and tried to take control, They cancelled his building permit and they stole his plans.” But he kept doing it anyway.

Once, when a staffer wrecked his car and called to confess the accident to him while he was mowing pasture, Coburn was more upset at being interrupted while mowing, an activity he treasured more than just about anything, than he was at his car being wrecked. The small and simple pleasures of life were enough, but he prized them.

There is an oddly personal postscript to this: The Federalist would not exist without Dr. Coburn. Without working for him, Sean Davis never would have met me, and the likelihood that this organization and the many lives it has touched would have been possible is very low. Every life has a ripple effect.

There was no man better equipped to face the end than Coburn, but the end kept being moved away from him. He’d be given death sentences from cancer over and over again, but survive and hold on and see more life happen for his nine grandbabies. There was no doubt in his mind about what comes after death, and what awaits those who believe. He went toward it with confidence because of that belief.

Coburn loved to quote Braveheart, especially when criticizing congressional leadership: “Men don’t follow titles. They follow courage.” So he was, to the end.