Although the Founders wrote and spoke with clarity and brilliance, it is evidently easy for us today to misunderstand them. The evidence is all around us.

David Boaz gives us a particularly vivid and therefore useful example of how it’s done in his book “The Libertarian Mind.”

“Introducing the American cause to the world, Jefferson explained:

‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness…’

Let’s try to draw out the implications of America’s founding document. Many libertarian scholars have joined Jefferson in making the case for natural rights to life, liberty, and property.” (Emphasis mine.)

You saw it happen, didn’t you? Jefferson did not declare that we have natural rights to life, liberty, and property. According to the Declaration, we have unalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Boaz has Jefferson “making the case” for natural rights to life, liberty, and property, but it was John Locke, not Jefferson, who did that. Had Boaz written that many libertarian scholars “have joined Locke in making the case for natural rights to life, liberty, and property” that claim would have been simply true.

My point is not to pick on Boaz or his valuable book. Because there are so many examples of Americans of all persuasions offering interpretations of the Founders which differ fundamentally from the Founders’ understanding of themselves, anyone whom I select for this discussion can seem to be unfairly singled out.

Christopher Hitchens offers another example. Although Hitchens was no libertarian, he also made Jefferson sound like Locke. In this passage from his well-received 2005 biography of Jefferson, Hitchens, like Boaz, dropped out “unalienable rights” and in addition managed to get both “property” and “natural rights” in the same sentence as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Watch closely to see how it is done:

“And where Locke had spoken of ‘life, liberty, and property’ as being natural rights, Jefferson famously wrote ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’”

In fairness to Hitchens and to Boaz, their depiction of Jefferson relying on Locke is standard fare. Open a book or article which discusses the Declaration and there is a good chance you will read that Jefferson put “the pursuit of happiness” where Locke had placed “property.” But stating it that way completely misrepresents the logic of what Jefferson did. Making it seem that Locke’s list and Jefferson’s list are essentially the same, that Jefferson only changed the last item of a list of three, leaves out the most important point. For Locke, property is the overarching concept:

“Man…hath by nature a power… to preserve his property—that is, his life, liberty and estate.”

Glossing over the antecedent of Locke’s list creates a false impression. To make that clear, let’s put Locke’s list and the Declaration’s list side-by-side:

“Man…hath by nature a power… to preserve his property—that is, his life, liberty and estate.”

“Men…are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,…among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Locke’s triad is appended to property. The Declaration’s triad is appended to unalienable rights. These are two fundamentally different accounts.

For the American Founders, unalienable rights—not property—is the overarching concept. Here is John Adams in the Massachusetts Constitution:

“All people are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.”

According to the Founders, our property rights are among our unalienable rights—and securing our unalienable rights is the very purpose of government:

“that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights…That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men.”

To provide an account of the Founders’ ideas which leaves out unalienable rights is to not account for them at all.

Jefferson was not following Locke—and he was also making it perfectly clear that he was not following Locke. Yet Boaz and Hitchens and scholars of every stripe and persuasion who already know going in that the Founders followed Locke always manage to find that the Founders followed Locke.

Of course, if you bring other convictions about the nature of things to your understanding of the Founders, you can manage to find other ways to misunderstand them. Here, for another example, is W.H. Auden in his book “The Dyer’s Hand”:

“It was then [during the administration of Andrew Jackson] that it first became clear that, despite similarities of form, representative government in America was not to be an imitation of the English parliamentary system, and that, though the vocabulary of the Constitution may be that of the French Enlightenment, its American meaning is quite distinct.”

Of course, representative government in America was never an imitation of the English parliamentary system, nor was the Constitution written in the vocabulary of the French Enlightenment—and all that was perfectly clear from America’s beginning. The vocabulary and ideas of the French Enlightenment were a far cry from those of America’s Founders.

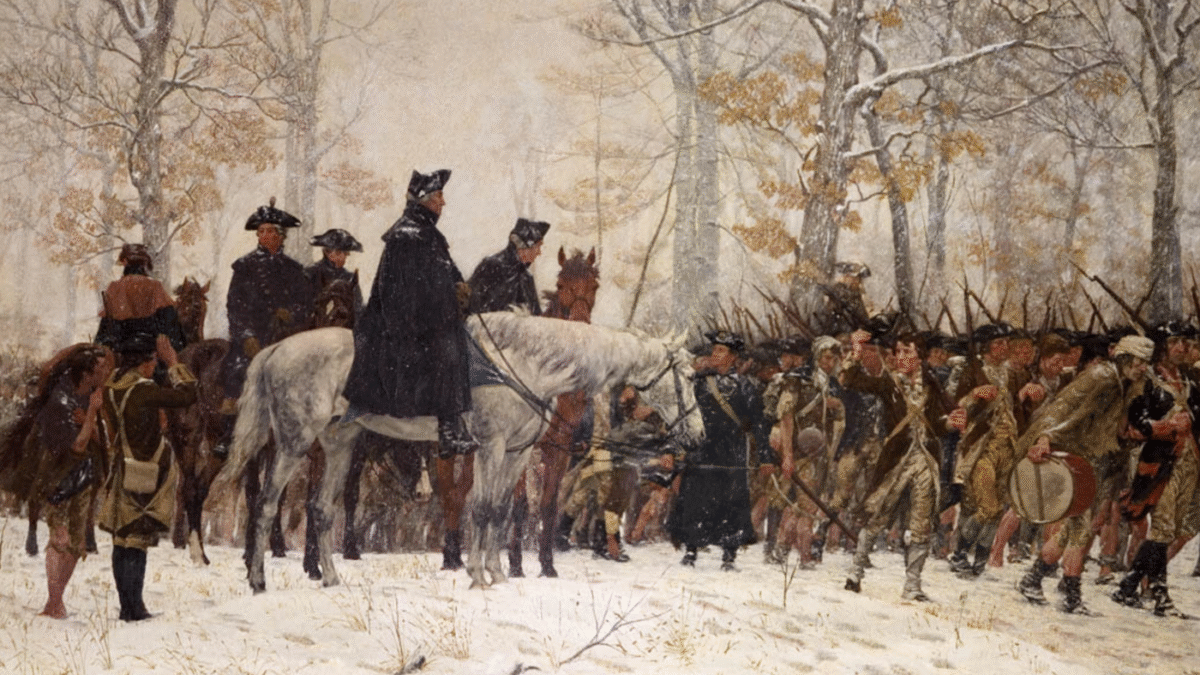

Voltaire’s “enlightened despotism” and Rousseau’s “general will” came together in a constitutional referendum by means of which the French imposed a new tyranny on themselves by granting Napoleon unlimited political power as their emperor. Americans, operating according to very different ideas and using a very different vocabulary, ratified the Constitution and then elected Washington to an office of limited powers in a government of limited powers.

Auden simply read into the Founders what he knew, the English parliamentary system and the ideas of the French Enlightenment, just as Boaz and Hitchens and others read Locke into the Declaration. Because our forgetting of the ideas of the Founders is widespread and very far advanced today, mistakes of this kind are frequently made—and usually go undetected. There was a time not so long ago when the ideas of the Founders were better remembered and more generally understood. Mistakes like these once would have been unlikely and, if made, quickly recognized.

I quote Auden as a reminder that we can encounter pronouncements about America almost anywhere, even in a book about poetry and literature. If we pay careful attention to these assertions wherever we encounter them, we will often find that they are mistaken, misguided, or misleading.