In Thursday night’s Democratic primary debate, candidate Beto O’ Rourke claimed that Americans should “mark the creation of this country not at the Fourth of July, 1776, but August 20, 1619, when the first kidnapped African was brought to this country against his will.”

O’Rourke’s comments were inspired by The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which “aims to reframe the country’s history” by placing 1619 as our true founding. The project is a collection of essays, literary works, and curriculum all aimed at this new understanding of American history. This project is dangerous enough as a misguided intellectual exercise, but its danger to our republic increases exponentially once put in the hands of a radical politician who could one day be president.

We Solve 1619 With 1776

Slavery is one of the worst human tragedies that has ever existed. For centuries, slavery has treated men and women like beasts. Chattel slavery in the United States was a depraved institution that created a despotic moral ecology and deprived millions of their most fundamental rights. Segregation too is one of the greatest blemishes on the American story. For decades, African Americans were not treated like full citizens and were subjugated to intense discrimination.

It’s hard to determine which historical images evoke more national pain and embarrassment: depictions of a slave’s back scarred with whip marks, stories of overcrowded ships with men and women chained to beds for weeks, or the film reels of little girls being sprayed with fire hoses and attacked by police dogs.

I am thus not arguing that such horrible national sins do not continue to have reverberating consequences. They obviously do. I am, however, arguing that by rejecting 1776 the 1619 Project is losing the best tools with which we can fight racism, injustice, and inequality. The principles of 1776 are what first freed America from Great Britain’s class system, emancipated slaves, and eventually ensured that all citizens, regardless of their skin color, would be treated equally under the law.

In the 1619 Project’s flagship essay, “Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. Black Americans have fought to make them true,” author Nikole Hannah-Jones writes that her dad always flew an American flag in their family’s front yard, but this confused her because she knew how much injustice her family, descendants of slaves, had endured.

She writes, “So when I was young, that flag outside our home never made sense to me. How could this black man, having seen firsthand the way his country abused black Americans, how it refused to treat us as full citizens, proudly fly its banner? I didn’t understand his patriotism. It deeply embarrassed me.”

Herein lies one of the biggest problems with the 1619 Project. Being ashamed of the shameful things in our nation’s history does not mean that we must be ashamed of our nation as a whole. I applaud Hannah-Jones’ father for honoring our nation’s flag despite his sufferings. Men like him have made our nation great.

The 1619 Project Is Bad History

The 1619 Project is bad history. You cannot trace America’s founding to Jamestown. It isn’t that simple. The United States began as 13 separate colonies, all with their own laws and cultures. You can compare Jamestown, founded for monetary gain by the Virginia Company, and the Pilgrims who landed in Massachusetts seeking religious liberty, but you can’t claim they were the same thing.

Further, 1619 was a very different time than 1776. As of 1619, John Locke had not yet written his “Two Treatises on Government,” nor had Montesquieu written “The Spirit of the Laws.” Both of these thinkers were greatly influential on the American Founders. While Montesquieu taught that republics are the best form of government and that power must be separated to prevent tyranny, Locke’s doctrines of religious toleration, consent of the governed, private property, and the equality of all men are foundational to the ideals of 1776, ideals that had not yet been fully espoused in 1619.

In his “Second Treatise on Government,” Locke writes that in a state of nature all men are born equal and independent. Picking up on this language, Thomas Jefferson writes in the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

In today’s egalitarian age it is difficult to understand how radical these ideas were then. Locke and Jefferson lived when kings still ruled much of Europe and claimed absolute authority over their subjects. Class structures were the norm. Anyone not born into the aristocracy was inherently treated as inferior. America was the first nation to recognize this fallacy and to enshrine legal equality into its identity. The American Revolution represented a radical break with Europe’s feudal past, scholar Harry Jaffa has written.

What did Jefferson mean by equal? Many on the left conflate the term equality with egalitarian. Jefferson never intended to level society, to reduce everyone to a standardized uniform sameness. This was the aim of the French Revolutionaries and later the communists. Jaffa comments that classical liberalism simply demanded that everyone have a fair and equal chance in the competition while modern liberalism demands that there be no competition at all. Classical liberalism demands the removal of artificial inequalities, but modern liberalism also demands the removal of natural inequalities. This is not what Jefferson had in mind.

‘All Men Are Created Equal’ Is Hope, Not a Lie

What Jefferson meant when he wrote that “all men are created equal” is that nature has not made distinctions between man and man as it has between man and horse. For any man to treat another man as he does a horse is against reason and nature. This is why slavery was so very wrong. Slavery wrongly allowed some men to act like gods and forced others into the role of beasts. It was the most unnatural institution that has ever existed. A regime in accordance with natural law does not rely on arbitrary power, but consent of the governed.

This is the founding legacy the 1619 Project and O’ Rourke so flippantly disregard. Hannah-Jones claims that the United States was founded on both an “ideal and a lie” because although our Declaration of Independence proclaims that “all men are created equal,” thousands of black men and women were denied these rights. I don’t believe Jefferson’s words were a lie, I believe they were a hope. He hoped that someday political circumstances would align with the natural laws he and his fellow Founders knew were right and good.

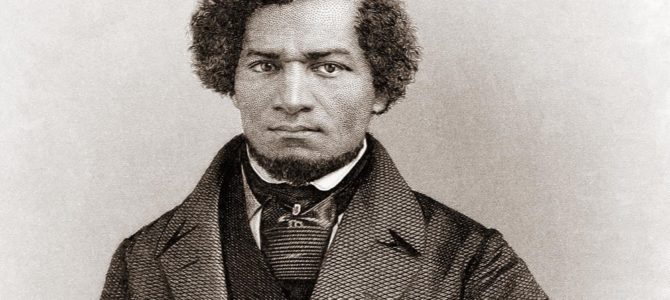

In his speech, “What does the 4th of July Mean to the Slave?” the famous African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass makes this argument also:

Pride and patriotism, not less than gratitude, prompt you to celebrate and to hold it in perpetual remembrance. I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.

Union or Utopia?

Often historical time periods are treated like fairy tales. The characters, events, and circumstances are simplified. We often forget that the Founders lived in a time with real political realities and complexities. Many of the Founders recognized the contradiction in their ideals and the existence of slavery.

However, the Founders also realized that real political solutions require real political choices. Their choice was between union and slavery. They chose union. It is fair to question their judgement, it is fair to disagree, but it is not fair to pretend this was not a difficult choice. Those at the Constitutional Convention knew that the powerful Southern states would never agree to a Constitution that outlawed slavery.

Without union, then, America would have been split between two or more countries. Along with this comes an entire host of problems, which Alexander Hamilton and James Madison explicate in the first half of the Federalist Papers. A sampling of their concerns: Endless petty wars like those they witnessed in Europe, the inability to protect themselves from foreign invasion if not united, and the difficulty of controlling interstate commerce.

Let’s also not forget that if the anti-slavery Founders chose to outlaw slavery outright instead of union they would have ceded control of slavery altogether in the South. This is the same problem Douglass ran into when he was part of the radical abolitionist group known as the Garrisonians.

The Garrisonians wanted the North to separate from the South. Douglass and others, however, argued that living in a slave-free country themselves would do nothing to help the millions stuck in slavery elsewhere. Of the Founders, Douglass said, “Their statesmanship looked beyond the passing moment…They seized upon eternal principles, and set a glorious example in their defense.”

The Founders Brewed a Poison Tea for Slavery

Douglass understood that the Founders chose to compromise for the sake of union. What he could not stomach was that those principles of freedom had still not been extended to African Americans 76 years later. This is not what the Founders intended. Although they agreed that slavery would continue for the time being, they also believed it would inevitably cease.

John Jay, known to some as the American Wilberforce, was an influential Founder who fought slavery for most of his political career. He wrote in 1786,

It is much to be wished that slavery may be abolished. The honour of the States, as well as justice and humanity, in my opinion, loudly call upon them to emancipate these unhappy people. To contend for our own liberty, and to deny that blessing to others, involves an inconsistency not to be excused.

The Founders ensured that within 20 years the slave trade would be outlawed. Even before the Constitution was ratified, the Continental Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, which outlawed slavery in new territories. That meant that over time the free states would come to outnumber the slave states and thus soon have the power to end slavery. For decades this law was referred to in the federal code as the third “Organic Law” of the United States.

None of this settled the issue, however, due to circumstances outside the Founders’ control. Like the other Founders, Jay believed that slavery would gradually disappear, and set up legal systems to hasten its destruction. He did not, however, foresee the advent of an ideology that would prevent the natural abolition of slavery he and the other Founders had planned.

In 1851 John C. Calhoun’s “A Disquisition on Government” was published posthumously. In this treatise, Calhoun espouses a theory of racial inferiority. This idea did not exist at the time of the Founding. It was a new innovation that led, as Hannah-Jones points out, to an ideology reinforced by racist pseudo-science and literature.

Building on Calhoun’s idea, Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy, argued that slavery should no longer be considered a “necessary evil” but a positive good. In fact, he argued that the Confederacy was the first government based upon the moral truth that slavery is a good.

This was a major shift from the thinking of the Founding period. Calhoun and Stephens’ theories were absolute and unequivocal rejections of the principles in the Declaration of Independence. Ultimately this argument over slavery led to the Civil War.

The Founders’ Legacy

Yes, Jefferson and many of the other Founding Fathers were hypocritical. They owned slaves. However, unlike the generation that followed, they did not try to justify their actions. In fact, they condemned themselves and in many instances attempted to end the institution. Jefferson, a slaveholder, wrote in “Notes on the State of Virginia,”

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submission on the other… And with what execration should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half of the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the others, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies…

The 1619 Project seems to find it easier to dismiss the Founders and Framers in one fell swoop versus dealing with the contradictions inherent in their characters, choices, and ideals. No one denies that Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington’s ownership of slaves is wrong, but it also does not mean that their glorious contributions to this nation and to the human story should be disregarded.

Of the Founders, Douglass said,

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men too — great enough to give fame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory…With them, nothing was ‘settled’ that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were ‘final;’ not slavery and oppression.

O’Rourke would have done better in the last debate to follow Douglass’s lead. It is fine to admit that our nation isn’t where we want it to be, that there is always more justice needed, but one does not need to deride the very foundations of our republic to make that point.

Douglass demanded more equality and justice in his day, but he did so while honoring the justice and equality the Founders had already provided. This type of nuance is lost in today’s soundbite politics, yet still sorely needed for our republic to endure.