During the midterm election campaign, Democrats pledged to help lower prescription drug prices. Since regaining the House majority in January, the party has failed to achieve consensus on precise legislation to accomplish that objective.

However, on Monday a summary of proposals by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA)—which became public via leaks from lobbyists, of course—provided an initial glimpse of the Democrat leadership’s policy approach. Party leaders claimed the leaked document describes an old legislative draft (they would say that, wouldn’t they?).

Indeed, the summary contains several bracketed numbers (e.g., “the catastrophic out-of-pocket threshold would be set at $[X] in 2022”), suggesting staff continue to finalize details based on Congressional Budget Office cost estimates and other considerations. But the document allows conservatives to analyze the good, the bad, and the ugly of House Democrats’ potential approach.

The Good: Realigning Incentives in Part D

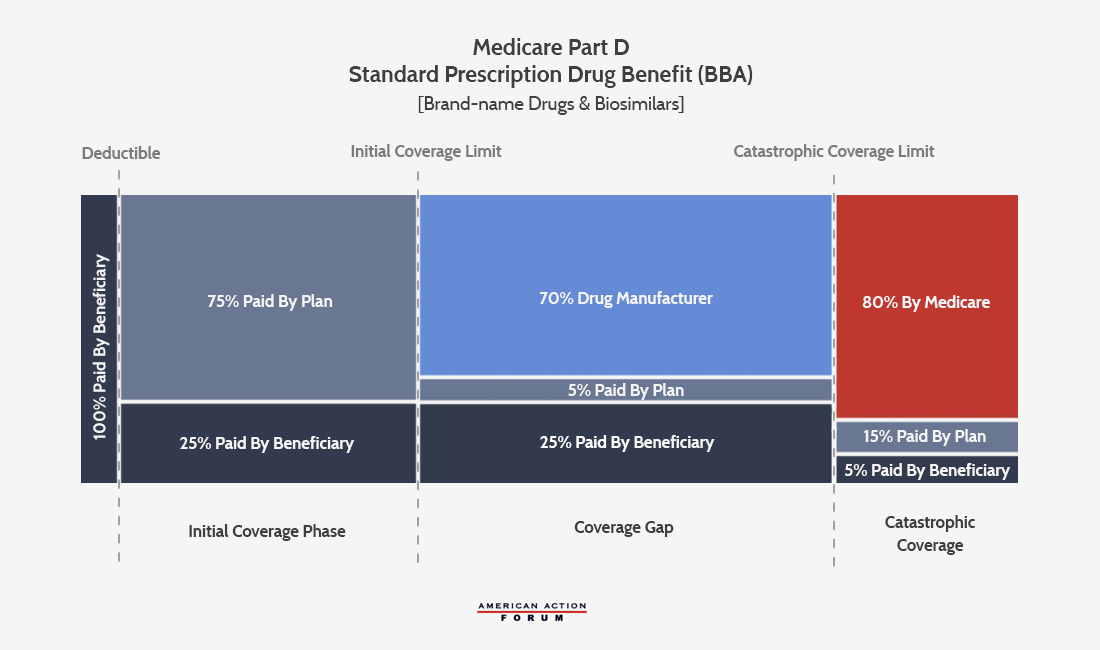

Among other proposals, the Pelosi proposal would rearrange the current Part D prescription drug benefit, and “realign incentives to encourage more efficient management of drug spending.” Under current law, once beneficiaries pass through the Part D “doughnut hole” and into the Medicare catastrophic benefit, the federal government pays for 80 percent of beneficiaries’ costs, insurers pay for 15 percent, and beneficiaries pay for 5 percent.

This existing structure creates two problems. First, beneficiaries’ 5 percent exposure contains no limit, such that seniors with incredibly high drug spending could face out-of-pocket costs well into the thousands, or even tens of thousands, of dollars.

Second, the very generous 80 percent federal reinsurance subsidy in the catastrophic phase provides a perverse incentive for insurers to have their beneficiaries reach this benefit level, at which point they can shift most of their costs to the nation’s taxpayers. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) and others have documented how these incentives have caused a shift in Part D spending, with the federal government spending more on reinsurance subsidies to insurers as they have shifted more individuals into the catastrophic coverage phase. Overall spending on Part D has also risen, due to the rapid increase in spending on high-cost beneficiaries.

The Pelosi proposal follows on plans by MedPAC and others to restructure the Part D benefit. Most notably, the bill would institute an out-of-pocket spending limit for beneficiaries (the level of which the draft did not specify), while reducing the federal catastrophic subsidy to insurers from 80 percent to 20 percent. The former would provide more predictability to seniors, while the latter would reduce incentives for insurers to drive up overall drug spending by having seniors hit the catastrophic coverage threshold and thus can shift most of their costs to taxpayers.

The Bad: Price Controls

The Pelosi document talks about drug price “negotiation,” but the policy it proposes represents nothing of the sort. For the 250 largest brand-name drugs lacking two or more generic competitors, the secretary of Health and Human Services would “negotiate” prices. However, Pelosi’s bill “establishes an upper limit for the price reached in any negotiation as no more than” 120 percent of the average price in six countries—Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom—making “negotiation” the de facto imposition of price controls.

Drug manufacturers who refuse to “negotiate” would “be assessed an excise tax equal to 75 percent of annual gross sales in the prior year,” what Pelosi’s office called a “steep, retroactive penalty creat[ing] a powerful financial incentive for drug manufacturers to negotiate and abide by the final price.” Additionally, the “negotiated” price would apply not just to Medicare, but would extend to other forms of coverage, including private health insurance.

As some have noted, Pelosi’s plan attempts to mimic President Trump’s drug pricing proposal, by using an international pricing index to bring down prices in the United States. The Trump administration’s efforts have highlighted how developed countries overseas free-ride on American innovation. By imposing price controls on their pharmaceuticals, other countries allow American consumers to pay a greater share of the research-and-development costs needed to create new pharmaceuticals.

But the solution to that dilemma lies in trade policy, or other solutions short of exporting other countries’ price controls to the United States, as outlined in both the Pelosi and Trump approaches. Price controls, whether through the “negotiation” provisions in the Pelosi bill, or related provisions that would require rebates for drugs that have increased at above-inflation rates since 2016, have brought unintended consequences whenever policy-makers attempted to implement them. In this case, price controls would likely lead to a significant slowdown in the development and introduction of new medical therapies.

The Ugly: New Government Spending

While the price controls in the drug pricing plan have attracted the most attention, Democrats have mooted some version of them for years. Price controls in a Democratic drug pricing bill seem unsurprising—but consider what else Democrats want to include:

With enough savings, H.R. 3 could also fund transformational improvements to Medicare that will cover more and cost less—potentially including Medicare coverage for vision, hearing, and dental, and many other vital health system needs.

In other words, Pelosi wants to take any potential savings from imposing drug price controls and use those funds to expand taxpayer-funded health care subsidies. In so doing, she would increase the fiscal obligations to a Medicare program that is already functionally insolvent, and relying solely on accounting gimmicks included in Obamacare to prevent shortfalls in current seniors’ benefits.

Price controls have their own drawbacks, as outlined above. But using any supposed savings from these price controls to expand an already unsustainable system adds injury to insult on future generations of Americans, providing good reason for conservatives to reject much of the Pelosi drug pricing agenda.