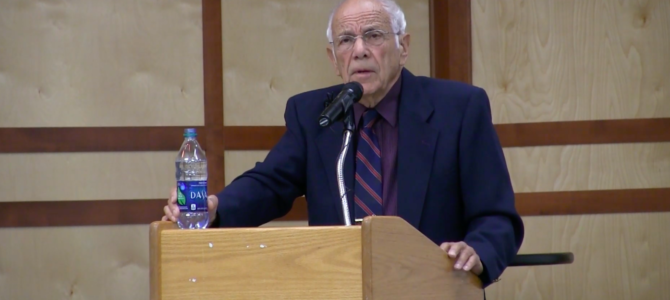

One of the 20th century’s greatest scholarly critics of totalitarianism, Paul Hollander, passed away last week. Although the Soviet Union and the Eastern communist bloc fell apart more than a quarter-century ago, we still deeply need thinkers like Hollander, and his loss will be all the more felt because the totalitarians he spent a career analyzing have burrowed so successfully into the very fabric of American institutions and cultural life.

I first read what is arguably Hollander’s chef d’oeuvre, “Political Pilgrims,” as a graduate student in the ’90s. It struck me then (as it still does) as one of the handful of books written by an American sociologist that one can safely say will still be timely in a century. I read many of Hollander’s other books over the years, and he quickly became one of my intellectual heroes.

He was born in Hungary between the two world wars, during the rule of Admiral Horthy, and he witnessed the collapse of the country first into a brief and bloody fascist regime, then post-World War II, into the condition of a vassal state to the Soviet dictatorship. He escaped the country in the wake of the Soviet invasion to crush the 1956 uprising and came to the United States. In short order, he embarked upon the career path of intensively reflecting on the causes of the catastrophes he had seen up close in his country of birth.

I cannot hope to summarize the full breadth of Hollander’s work here, although I have made an effort to do that elsewhere. Perhaps the single most important question Hollander pondered was this: How is it that cultural elites—people whose livelihood depends on a high level of intellectual performance—can so easily and so frequently fall into a form of political identity that involves championing ideas and regimes that produce massive human suffering?

His conclusion was that it is typically the combination of utopian idealism, an unrealistic view of human nature, and a deep resentment at the relative deprivation these radical intellectuals tend to suffer vis-à-vis other elites with less educational (but more economic capital) that explains the phenomenon.

So great is their adherence to the wild-eyed political dreamworld that intoxicates them that such intellectuals will not be deterred by the failure of any particular utopian political project, or indeed by the collapse of the entire global narrative on communism as the human solution to suffering. Just as they moved from Stalin to Mao to Castro to Hugo Chavez, they will find other totalitarian models to venerate when all the communist options are gone, as they seemingly are today.

Islamism, Post-Communism?

Paul predicted that after communism collapsed Islamism might well become the next big thing for such utopian intellectuals. Such individuals would find sympathetic the attack on modernity and Western civilization that Islamists mount.

The outrage of Western radical intellectuals at the Danish Mohammed cartoons or the suggestion of some that the staff of Charlie Hebdo got what they deserved demonstrate how right Paul was. His analysis also aids in comprehending the enthusiastic fawning among the intellectual class over far-leftist Muslim activists Linda Sarsour and Ilhan Omar, the sweet-faced Muslim congresswoman from Minnesota who recently referred to the 9/11 attacks in flippant language.

The novelist Michel Houellebecq provided a perfect literary example of the phenomenon Paul catalogued and theorized in his many books and articles. In his recent novel “Submission,” Houellebecq envisions the coming to power of an Islamist regime in France. A central thread in the narrative details how leftist French intellectuals such as the novel’s narrator are brought over to the new regime’s side.

The emergent Islamist leader, Ben Abbes, begins by endlessly flattering the intellectuals, telling them how admirable they are in their intellectual purity and abstraction, and how deserving they are of the material goods of which they are deprived, goods that are hoarded instead by the business class the resentment-filled left intellectuals despises with a visceral fury.

The Islamist regime gives them yet another seamless, simplistic, one-size-fits-all answer, abstract grand system that they can wield in their merciless way to resolve every moral, political, and scientific problem conceivable. Finally, Abbes provides them with a charismatic, strong leader, mouthing always the sweet discourses of “total justice,” “the welfare of the people,” and “the vanquishing of the oppressors,” however cynically.

This last is the most important, Houellebecq knows, and Hollander as well. The leftist utopian intellectuals, despite their flowery talk of egalitarianism and the anarchist need to challenge hierarchy, simply cannot leap quickly enough into line when a Lenin, or a Che Guevara, or a Ben Abbes alerts them that the time has come (at last!) to take up arms (however figuratively) in service of the Great Leader of the People.

It is almost as though intellectuals cannot help but fall under the spell of such men, not in spite of their commitments to abstract reason and independence of thought, but because those commitments are merely empty games they play only because they are denied other, more direct methods for self-assertion. In their deep heart of hearts, they want to be Ben Abbes. Since they cannot, the best they can do is to align themselves with him, and fawningly admire his power.

The list of such intellectuals who aligned themselves with the dictatorial, murderous thug regimes of the 20th century is long and distinguished. Hollander was one of the chief chroniclers and critics of this phenomenon. He is irreplaceable.