The opioid crisis continues to ravage the country, destroying lives. Despite attention from policymakers and the medical community, the crisis hasn’t abated — and some experts predict it will get much worse.

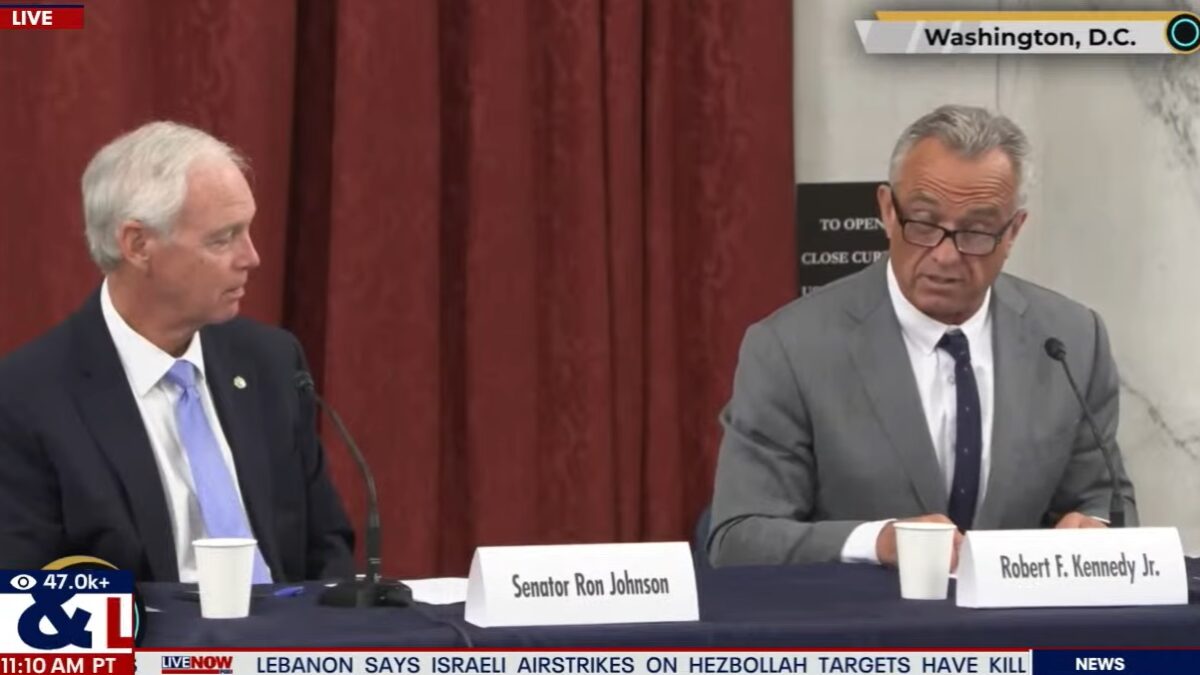

In January, I testified at a hearing on this issue held by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs. The Committee Chairman, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), had noticed the same thing I had while I worked at the Maine Department of Health and Human Services: States that expanded Medicaid were seeing the largest increases in opioid deaths.

The hearing explored the connection between Medicaid and the opioid problem — a timely question given that advocates of expanding Medicaid to able-bodied adults are aggressively pushing the dubious narrative that Medicaid expansion is the best strategy to combat the crisis. Johnson issued a comprehensive report showing that trafficking in Medicaid has fueled the drug crisis and that a correlation exists between states that expanded Medicaid and those that experienced major increases in overdose deaths.

Advocates for Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion touted their usual response, saying that the opioid crisis began before Obamacare expansion. But even prior to Medicaid expansion to able-bodied adults, the program was growing rapidly — at the same time the opioid crisis was taking hold. The number of able-bodied adults ages 18 to 64 on Medicaid has quadrupled since 2000, up from seven million to 28 million today.

When Maine first expanded Medicaid to able-bodied adults in 2001, the state saw a major spike in drug overdose deaths, jumping from 50 to more than 150 in two years. Most of those deaths were from prescription drugs. Medicaid expansion may not have single-handedly caused the opioid crisis, but there is good reason to believe that Medicaid expansion has added fuel to the fire.

A recent report issued by West Virginia — the state at the epicenter of the opioid crisis — sheds more light on the issue. West Virginia is the national leader in the category of drug overdose deaths, most caused by illicit and prescription opioids. In 2014, the state expanded Medicaid to able-bodied adults, adding 160,000 adults ages 18-64 to Medicaid. During that time, overdose deaths increased from 627 in 2014 to 884 in 2016.

West Virginia’s Department of Health and Human Resources analyzed every overdose death in the state in 2016 — and what they found is disturbing. According to the report, nearly three out of four people who died of an overdose had been on Medicaid at some point in the year before they died.

Seventy-one percent had been on Medicaid in the 12 months prior to their death and 67 percent had Medicaid for at least the entire year prior to their death. Eighty-one percent of women who passed away from an overdose had been on Medicaid that year.

Most of the individuals who passed away were using their Medicaid benefit to get free prescription opioids — in the 12 months before passing away, “56 percent of decedents had filled an opioid prescription.”

And while illicit drugs are the major killers, it is not just heroin and fentanyl that are causing these deaths. According to the report, 80 percent of white females and 63 percent of white males had a prescription drug in the toxicology report at the time of death. Prescription drugs were involved in most of these deaths — prescriptions that were likely paid for by Medicaid.

Here’s the bottom line: Medicaid is a deeply flawed program that dispenses prescription opioids at a staggering rate.

While the opioid crisis continues to rage around the country, we need to recognize and study the clear connection between Medicaid and opioid abuse. States should not view Medicaid expansion as a solution to the crisis — even pro-expansion doctors have admitted it is not a silver bullet.

Instead, policymakers need to question if rather than curing the opioid crisis, Medicaid may be complicit in it.