For better or for worse, sighing songstress Lana Del Rey is no more. Yes, she’s still writing music and performing it, but her creator (Lana Del Rey is the stage name of New York native Elizabeth Grant) doesn’t seem to need her sadgirl shtick anymore.

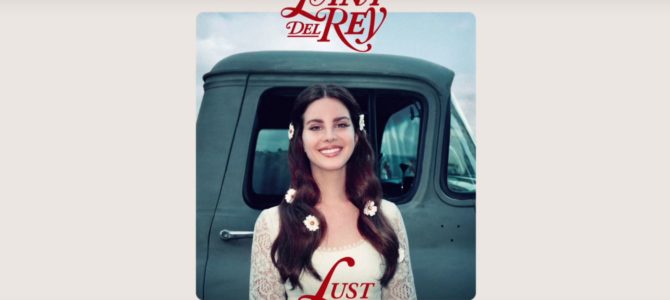

Her Grammy-nominated album “Lust for Life,” released in 2017, signals a shift to a lot more of activist Grant and a lot less of ingenue Del Rey in the years to come. It’s a tradeoff that comes with responsibilities Del Rey doesn’t completely understand.

“Lust for Life” is unlike her previous albums, and not just in cover art. It’s more than symbolic that the 2017 album marks the first to picture Del Rey smiling. Her other albums were character studies in self-destruction from the vantage point of a wandering woman often wounded by the men in their lives. Del Rey was a beautiful, melancholy confection, and scores of millennial women connected with her gritty, aching, and often sexual songs sung in a breathy vibrato.

Surely, few could truly relate to lyrics about running away to join a motorcycle gang or being a kept woman, but they escaped in it. Now Del Rey has popped that bubble with her “more socially aware” album.

Can She Be Both Artist and Activist?

Del Rey maintained an anachronistic aura for years, starting with 2012 album “Born to Die” and its songs focused on heartache and the pointlessness of living. Contemporary issues were outside the singer’s purview, and her character’s penchant for pinning all her hopes on the leading man in each of her songs earned dismissal from many feminists.

Del Rey also drew criticism for dismissing feminism as “not an interesting concept” in a 2014 interview with Fader magazine. She preferred writing songs about sugar daddies with “cocaine hearts” (2012 song “Off to the Races”) — until “Lust for Life,” which she is promoting in a world tour until April. I saw Del Rey perform in Charlotte, North Carolina, on January 30. She sang surprisingly few songs from the new album, but the ones she did were the political ones.

Something must have made Grant decide to imbue the once-ethereal Lana Del Rey with time and place. She’s no longer a character like David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust; Del Rey has crossed the line from character to citizen.

In February 2017, Del Rey put a hex on Donald Trump. She wrote a song inspired by the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, “God Bless America – And All The Beautiful Women In It,” for “Lust for Life” (she performed it in Charlotte). After President Donald Trump’s election, she stopped using the American flag motifs she relied on in performances and music videos.

Perhaps some lyrics in her song “Change” offer a glimpse into her thought process: “I’ve been thinkin’ it’s just someone else’s job to care/ Who am I to wanna try? But/ Change is a powerful thing, people are powerful beings/ Tryin’ to find the power in me.”

One song not on the setlist was “Cola.” It’s a controversial song with a passing reference to Harvey Weinstein that Del Rey “retired” in November 2017 after the scores of sexual assault allegations against the mogul. That’s why I was surprised when Del Rey included her 2014 song “Ultraviolence” in the January 30 performance. She didn’t perform half the songs from her new record, and out of her approximately 70 songs she chose to croon one with the lyrics “He hit me and it felt like a kiss.”

You Can’t Be a Role Model if You’re Not Real

When Del Rey was merely a character, many listeners let lyrics like the above slide. She couldn’t be a role model because she wasn’t real. But now, Del Rey is mixing fiction with real life as she charges her listeners to act, to change the world they share. How can she reconcile her questionable songs with the moral high ground she seems to be taking with publicizing her political views? And will Del Rey’s artistry withstand her new focus?

The Federalist senior writer Robert Tracinski warns of the dangers art faces in this new, politically correct Age of Didacticism. He writes that good art highlights subjects “that are interesting on their own terms, not merely as illustrations to accompany a treatise.” That’s the risk Del Rey runs as she turns from filtering her experiences through the lens of her stage persona and toward writing anthems about the state of the world.

By turning her gaze to culture at large, it seems Del Rey is losing the countercultural streak that endeared her to so many. As a vulnerable character, Del Rey is approachable because she clearly is in no position to judge others. Her songs show that she, too, made mistakes in her youth (“This Is What Makes Us Girls”), fears abandonment (“Dark Paradise”), and wonders about death (“Summertime Sadness”). The current question is whether her songwriting continues to stand out or blends in with the other musicians caught between what’s trendy and what’s transcendant.