Most people wouldn’t take issue with the U.S. government inquiring about citizenship status in a population census, but in 2018 some Democrats consider it a radical act to ask the simple question, “Are you a U.S. citizen?”

Perhaps this doesn’t surprise you given the way liberals responded to Democrats’ loss in the government shutdown fight over the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and their outrage over the White House immigration plan that would grant 1.8 million of them amnesty (a framework ironically also panned by immigration hawks on the right).

Still, the brazenness of the liberals’ indignation over this census question is really something to behold. The outrage started with a December 2017 letter from the Department of Justice to the Census Bureau requesting that the Bureau reinstate a question on citizenship in the upcoming 2020 Census. This query had been included on the “long-form” census as recently as the year 2000, one census ago.

At last printing the question read: “Is this person a CITIZEN of the United States?” Respondents are not asked to detail their legal status, only to answer whether or not they are a citizen.

The DOJ says it wants to reinstate this question to get an accurate count of the citizen voting-age population within localities in order to enforce Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act that exists to protect citizens against discrimination, such as vote-dilution based on gerrymandering. The DOJ adds that federal appeals courts have repeatedly held that in vote-dilution cases hinging on citizenship rates, citizen voting-age population is the proper metric for determining the legality of district maps.

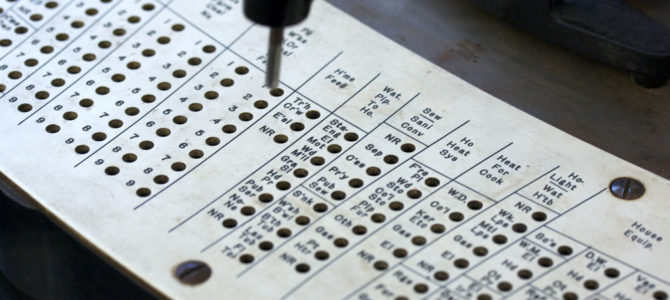

During the time the Census Bureau administered the citizenship question, one in six households received it. When the American Community Survey (ACS), which includes a similar question on citizenship, replaced the long-form census in 2010, only one in 38 households received it.

This creates a series of statistical issues for the relevant authorities when it comes to drawing up and confirming the legality of voting districts, involving apples-to-apples discrepancies between census and ACS data, timing mismatches and sampling issues forcing authorities to make imprecise estimates — all to the detriment of data integrity. The DOJ argues these problems would be mitigated by having one clean data set, which would be achieved by including the citizenship question in the census.

The DOJ presents a legally, politically and practically powerful argument. To ensure minority voters are not disenfranchised, DOJ needs accurate citizenship information. To protect minority voters would theoretically please Democratic foes of the Sessions-led DOJ, who claim to be the “true champions” of voting rights. Reinstating the citizenship question would solve a host of data-related problems impacting redistricting and related litigation.

The merits of the DOJ’s case notwithstanding, one would think it reasonable for the government and the public to have reliable figures on citizenship. But this is beyond the pale for Democrats.

Democrat Sen. Dianne Feinstein, she of the sanctuary city bastion of California, recently wrote to the Commerce Department expressing her “serious concern” over the DOJ’s “deeply troubling” request, pleading against the reinstatement of the question. What does Feinstein fear about the American people knowing who lives among them?

First, she raises the practical concern that as the census preparation process is already delayed, there is insufficient time to test the “impact and effectiveness” of the question. This is a weak argument, since again the Bureau included the question in each long-form census from 1970 until 2010.

Second, in spite of her argument that the Bureau lacks the time to evaluate the question, Feinstein speculates that including it “would likely depress participation in the 2020 census from immigrants who fear the government could use the information to target them.” But did this same risk not exist from 1970 to 2000? Since the question does not ask illegal aliens to identify themselves as such, what exactly should non-citizens or their cohabitants have to worry about? More fundamentally, why is it Feinstein’s concern whether such individuals choose not to participate, presumably out of fear law enforcement might justifiably pursue them? Is not Feinstein’s first responsibility to U.S. citizens?

Hers third major concern answers this last question. She writes: “This chilling effect [of reinstating the question] could lead to broad inaccuracies across the board, from how congressional districts are drawn to how government funds are distributed. Rather than preserve civil rights, as the Justice Department claims, a question on citizenship in the decennial census would very likely hinder a full and accurate accounting of this nation’s population.”

On the latter point, the DOJ’s rationale for reinstating the question is specifically about preserving the civil rights of American citizens, something Feinstein just shrugs off. On the former point, she is right. Census figures are indeed not only critical to drawing congressional districts, but also, as Feinstein notes earlier in her letter, to determining congressional apportionment — how many representatives each state sends to the House. Consequently, the census numbers dictate how many electors represent each state in the electoral college. The census thus determines to a large degree the political power of each state.

Here is the rub: Since apportionment is determined by population size — citizens plus non-citizens — legislators primarily (though not exclusively) from blue states with substantial illegal alien populations have a vested interest in high census participation rates among illegal aliens. Democrats in particular also fear that as state and local governments may be permitted to draw electoral districts based upon eligible voters, i.e. citizens, and census citizenship data would enable them to draw such districts, the end result could be a reduction in urban blue districts that exist now because population figures are enlarged by ineligible illegal aliens.

The power of the census does not end there. Feinstein writes that census data “are used for allocating billions of dollars in federal funding.” According to a September 2017 Census Bureau report, in 2015 132 programs doled out $675 billion in federal funds on the basis of Bureau data, including the census. That the census has such a disproportionate influence on where tax dollars go — funds allocated in part by population figures artificially inflated by non-citizens — is precisely why voters deserve to know the citizenship status of those living among them.

Again, politicians like Feinstein from blue states with large illegal alien populations have an incentive for non-citizen participation rates to be as high as possible, because it means they can bring home more bacon for their constituents. As the power to tax is the power to destroy, the power to redistribute is the power to build … a loyal voter base.

Last but not least, by failing to compile citizenship data, politicians can prevent their constituents from having an accurate picture as to the extent to which they are subsidizing non-citizens broadly, and illegal aliens in particular. While California’s populace may be so radical on immigration that Feinstein might not find her seat threatened under the disinfectant of sunlight on citizenship, congressmen and women from other states might.

In sum, Feinstein’s argument on the importance of census data proves exactly why it is imperative to reinstate the citizenship question.

The unwillingness of our representatives to support the disclosure of citizenship data also explains the paucity of uniform and comprehensive non-citizen crime data. Leaving aside that criminals generally do not self-identify as illegal aliens, it is apparent that our government resists transparency because what numbers we do have tend to indicate the disturbing extent to which illegal aliens — including DACA-eligible ones — commit crimes.

The facts are detrimental to the political class’s prevailing narrative. Democrats believe going soft on illegal aliens will bear fruit in the form of millions of future Democrats, ensuring national political dominance. Corporatist Republicans view illegal aliens as cheap labor. The “forgotten man” bears the costs.

Feinstein did not always sing such a radical tune on immigration. Nor did Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, who in 2009 stated something that would get him banished from the party he leads in 2018: “People who enter the United States without permission are illegal aliens and illegal aliens should not be treated the same as people who entered the U.S. legally.”

What has changed are the political incentives for holding such positions. With the weaponization of identity politics, immigration is wielded as a cudgel such that supporters of national sovereignty and the rule of law are cast as bigots. Meanwhile, the cudgel-wielder is heralded as the virtuous hero, standing with the downtrodden and oppressed, victims of illegal immigration be damned.

And so we face a situation today in which non-citizens are treated as a protected class whom our elites seems to prefer over deplorable Americans. This was perhaps the seminal meta-narrative of the 2016 presidential election that resulted in Donald Trump. But have our betters learned anything?