This week, Americans will gather around kitchen and dining room tables from sea to shining sea for one of our most distinctly American celebrations. For generations, we’ve marked the fourth Thursday in November as a national day of thanksgiving.

At the end of this fractious year, coming together in gratitude may feel difficult. In a nation that seems to be fraying at the seams—battered by racial tensions, political turmoil, bloodshed, and scandal—exactly what do we have for which to corporately give thanks?

It’s not as if our national discord is contained to the halls of Congress or the editorial pages; it invades our daily lives. When we can’t even watch the Lions game or get a second-rate cup of coffee from grandma’s Keurig without political implications, has Thanksgiving become a meaningless exercise in whistling past the graveyard?

Thankfully, the roots of our Thanksgiving celebration—like the discipline of thanksgiving itself—go deeper than happy feelings over food and football. Most of us know the story of the first Thanksgiving, celebrated by that tiny band of Separatists at Plymouth in 1621. However, we may not realize that our modern Thanksgiving celebration originated in our nation’s worst period of turmoil and bloodshed: the Civil War. In that story, there are lessons that can help us today.

How the Civil War Led to Thanksgiving

It’s a fairly simple tale. In America’s early days, thanksgiving celebrations were sporadic and mostly regional affairs. The popularity of the holiday began to grow in the 1840s and ‘50s, thanks primarily to the dogged efforts of author and poet Sarah Josepha Hale. As literary editor of the widely read Godey’s Lady’s Book, Hale used her platform to advocate a national, unified Thanksgiving Day. Besides writing multiple Thanksgiving editorials, she lobbied state governors and wrote to one U.S. president after another, finding more success with the former.

In the meantime, affairs in the United States were growing increasingly rancorous. In the bitter years immediately preceding the outbreak of war, Hale promoted her national Thanksgiving Day as a way to find unity. In 1860, she wrote: “Everything that contributes to bind us in one vast empire together, to quicken the sympathy that makes us feel from the icy North to the sunny South that we are one family, each a member of a great and free Nation, not merely the unit of a remote locality, is worthy of being cherished… We believe our Thanksgiving Day, if fixed and perpetuated, will be a great and sanctifying promoter of this national spirit.”

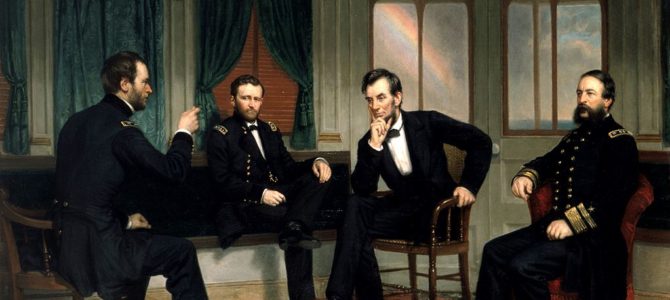

It was not to be, of course. By the autumn of 1863, Americans had already seen more than two years of war’s devastation in their towns, farmland, and families. The nation was freshly reeling from the Battle of Gettysburg, which had claimed the lives of 51,000 men that July. While terrible in its toll, Gettysburg marked a turning point in the war—a decisive Union victory that ended Confederates’ hopes of invading the North. At the same time, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was making a name for himself in the West, showing badly needed military leadership on the Union side. The tide was turning.

At this time, perhaps due to these victories, Hale’s cause suddenly broke through at the White House. Shortly after receiving a letter from Hale, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for a national day of thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday that November. November 26, 1863, marked the first in a now-unbroken line of American Thanksgiving holidays.

Lincoln’s wartime Thanksgiving proclamations of 1863 and 1864 are well worth reading. Besides providing a window into our history, they can also teach us what it means—and how it helps—to give thanks in the midst of national strife.

Lessons from Lincoln: First, Seek God

Perhaps most noteworthy is the clear religious tone of the Thanksgiving proclamations. Lincoln did not call for vague, general gratitude of the sort we find in modern Hallmark cards. Rather, he called for “thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens,” and even more strongly in 1864, “thanksgiving and praise to Almighty God, the beneficent Creator and Ruler of the Universe.” Lincoln couldn’t have been clearer in his belief that thanksgiving must have an object, and that the proper object—the Giver to whom thanks is due—is Almighty God.

This is important especially when times are troubling and uncertain. As Lincoln’s audience knew all too well, our earthly blessings—home, friends, family, and life itself—can be lost in a moment. As I wrote at Thanksgiving a few years ago: “While gratitude based on temporal things will eventually fail us, thanksgiving is an act of communion with the eternal God. As such, it anchors us to something that will last forever.” For precisely this reason, the Bible speaks of thanksgiving as part of the antidote to anxiety.

Is there anything more characteristic of our culture in 2017 than anxiety and fear? It is what drives so much of the violence and vitriol we see: mutual distrust between Left and Right, and fear of a future in the other’s hands. We would be well-served to remember that both Left and Right are under the care and authority not of Congress or President Trump, but of “the beneficent Creator and Ruler of the Universe.” Through thanksgiving and praise to him, we can take our eyes off our uncertain circumstances and place them instead on the unchangeable God.

Rediscover Repentance

While proclaiming a day of thanksgiving, Lincoln also calls for repentance. In his 1863 proclamation, he calls on Americans to pray “with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience.” The following year he sounds even wearier, asking citizens to “reverently humble themselves in the dust and from thence offer up penitent and fervent prayers.”

Notice what isn’t said. There is no finger-pointing, no claiming of the moral high ground, no shaming of the evildoers. Lincoln speaks not of “their” but of “our” perverseness and disobedience. In the same sentence, he acknowledges the human toll of the conflict, asking for prayers on behalf of “widows, orphans, mourners, [and] sufferers.” It’s a passage that speaks not of anger or blame, but of deep sorrow and self-examination.

We could all learn a lesson here. In our outrage culture, we often start pointing fingers before the casualties of the latest horror have even been laid to rest. There is little reflection, little grieving, little repentance. Having done away with the notion of God as judge of all mankind, we’ve appointed ourselves in his place, which doesn’t allow us to acknowledge our own failings.

This is not to suggest that society should never render judgment on moral questions, but that it should do so with the humility of looking first for the logs in our own eyes. Our end goal should be not wholesale condemnation, but restoration—just as each of us has at times needed to be restored.

Look for Blessings, and See Them as Mercies

Finally, Lincoln points out that even in the midst of unimaginable trial, there are daily mercies for which we can give thanks. His proclamations list many of them: fruitful fields and healthful skies; peace with foreign nations; a flourishing industrial economy; health on battlefield and home front; growth of the free population “by emancipation and by immigration”; and the fortitude to withstand the trial at hand.

“No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things,” Lincoln hastens to add. “They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.”

This is the opposite of the way we tend to view the world. We see provision, order, and prosperity as the norm—no more than we deserve. It’s the hardships, the difficulties, the times of want and suffering that are aberrations to the natural order. If we took an honest look at the whole of history, however, we would see that the peace, order, and prosperity we currently enjoy are remarkable anomalies of the human experience. Further, they are not only blessings but mercies—far beyond what we deserve.

Thanksgiving and repentance share a common premise: that both mankind and the world we inhabit are fallen. We are bent toward evil, and life is bent toward suffering. While this may seem a depressing perspective, in truth it is a freeing one. It frees us to rejoice in daily blessings, even in the midst of hard times. It frees us to see our fellow humans with mercy, just as we often require mercy. It frees us from the worrisome burden of being our own sovereigns and moral authorities, allowing us to worship and trust the God who is.

With all respect and gratitude to Sarah Josepha Hale, it’s clear that her vision of a Thanksgiving holiday as the miracle cure for a fractured nation was naïve. The act of humble thanksgiving itself, however, could serve us very well—today as always.