Donald Trump may well obliterate the GOP’s prospects for the coming decade or longer. Despite much wishful thinking among liberals, however, big Republican losses in Virginia yesterday do not prove this contention. There’s really nothing unprecedented about cyclical pushbacks in politics. And if every election were really imbued with the kind of game-changing importance that political pundits claim, it would mean Americans were going through massive ideological fluctuations every year, which seems unlikely.

A theory: Even if Virginia GOP gubernatorial candidate Ed Gillespie had mimicked Trump’s populism to complete perfection, he would have lost anyway. As it is, he outran Trump by 1 percent. The idea that Trumpism — however people define it — is especially popular in general or popular in a state with many Democrats is merely theoretical considering no one other than Hillary Clinton has been beaten by it in an open election.

There are two types who want us to think there was a sea change among the GOP over the past year: liberals who want to paint all Republicans as a bunch of white supremacists and Trump populists, and those who are trying to convince everyone that post-World War II conservatism is dead. Neither of these things are true.

What’s more plausible is that Trump’s victory was predicated on general distaste for Hillary Clinton, and after eight years of a progressive White House, people voted for a Republican. As it is, voters tend to embrace change after two-term presidencies. The majority of GOP candidates ran ahead of the president in their states in 2016, and most ran on traditional conservative issues.

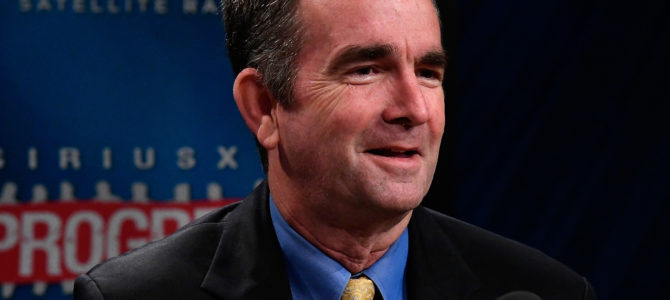

Another theory: Republicans would have lost Virginia even if Mitt Romney or Marco Rubio were president. They would have lost even if Congress had passed tax reform and overturned Obamacare. Virginia is a blue state. Clinton won Virginia, handily. So did Barack Obama, twice. Winning a blue state in what is by any historical standard a good environment for blue candidates is exceptionally normal. The majority of the seats Republicans lost yesterday leaned Democrat or were competitive to begin with, and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Ralph Northam ran a milquetoast, moderate campaign, even promising to work with the president. Hardly resistance-level stuff.

“We learned the resistance to Trump is energized, active, engaged, which we’ve seen around the country,” claimed Sen. Richard Blumenthal. “The cruel and heartless proposals from this administration have touched a nerve of opposition. People are energized like never before.”

Actually, voters are always this energized. They just happen to be a different set of voters. In 2009, the first year of the Obama presidency, when conservatism was forever buried and the president boasted high favorability numbers and legislative accomplishments, there were gubernatorial elections in both New Jersey and Virginia, as well. In both cases the governorship changed hands from Democrats to Republicans. (I don’t recall much talk about these results being a rejection of all liberalism and Obama’s policies, but perhaps that was the takeaway.) In 2001, a year into George W. Bush’s first term, Democrats took back the governorships in New Jersey and Virginia from Republicans.

It’s conceivable that the GOP will be trounced in the 2018 midterms. It’s likely, in fact. Since 1862, the president’s party has averaged 32-seat losses in the House in the first midterm after his election. In 2010, Republicans gained 63 seats in House only two years after a resounding Obama victory. The only difference would be that Democrats used their two-year window of power to pass a massive entitlement program. Republicans don’t seem to have the courage to pass even piddling reform.

Republicans deserve to be admonished for their poor organization and bad candidates. They may be able to mitigate their losses by scoring some legislative successes. Republicans are impotent and in disarray. This is obvious.

Was the Virginia loss also a backlash against the president? I’m sure that’s part of it, too. Trump is historically unpopular, and his presidency has become the all-consuming topic in Washington. But Virginia was not unique. Arguing that these conventional political losses denote colossal shifts in American politics is disingenuous unless you can explain why these results are different from what’s happened in the past.

The more likely explanation for what’s going on is that our votes aren’t as well-thought-out as pollsters imagine. Maybe elections — both presidential and local — tell us less than we think. Maybe voters are instinctively averse to those in charge because those in charge always let them down. And maybe once a president is elected, the other half intuitively begins working to strip him of power. Maybe politics is a tribal endeavor rather than a policy-driven decision.