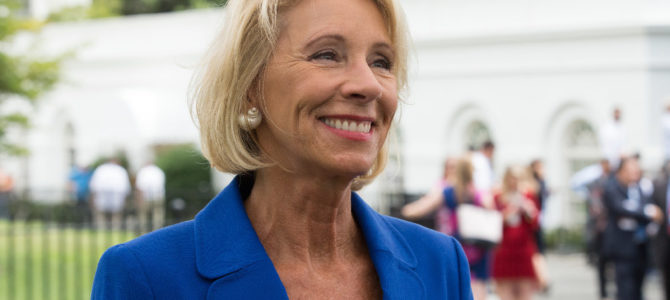

“The era of ‘rule by letter’ is over,” Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said Thursday afternoon, in reference to an Obama-era practice of issuing guidance documents that acted as laws. DeVos’ speech signals yet again her agency’s willingness to end the injustices that spread under the Obama administration, which made women into unquestioned victims and treated men as perpetrators without giving them a chance to defend themselves.

“Through intimidation and coercion, the failed system has clearly pushed schools to overreach,” DeVos told an audience at George Mason University’s Arlington campus. She also accused the former administration of “weaponized” federal guidance documents that “work against schools and against students.”

This was the first time a federal official spoke publicly about the need for due process and the presumption of innocence while highlighting instances where students had been falsely accused. It was also a welcome change from the guidance the Obama administration issued in 2011. At the time, the “Dear Colleague” letter issued by the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) greatly changed how schools would be required to adjudicate accusations of sexual assault to retain access to federal funds and prevent federal investigations.

We Don’t Need Law to Compel You

Although federal guidance doesn’t carry the weight of law, the 2011 Dear Colleague letter was treated as legally binding, and schools were threatened with a loss of funding if they did not adhere to the administration’s demands. Former assistant secretary for civil rights at the Education Department Catharine Lhamon said as much at a summit in 2014, insisting the guidance wasn’t “an empty threat” and that she had already threatened schools with a loss of funding for non-compliance.

The creation of the guidance did not follow the Administrative Procedures Act, which requires substantive new regulations to go through a notice-and-comment period before being enacted. Threatening funding would qualify as substantive.

The 2011 letter also forced schools to adopt the low “preponderance of the evidence” standard when adjudicating sexual assault, which meant administrators just had to be 51 percent sure a sexual assault took place (meaning they could be almost just as sure the assault did not take place). The justification for this, which came after Oklahoma Sen. James Lankford asked, was that most schools were already using the standard. This, obviously, is not a legal justification for anything.

Our Solution: More Meetings

To fix the current system, which DeVos insisted “isn’t working” and kept referring to as “failed,” the education secretary vowed to send the current guidance through the notice-and-comment period to “seek public feedback and combine institutional knowledge, professional expertise and the experiences of students to replace the current approach with a workable, effective and fair system.”

She cited proposals and critiques from the American Bar Association, the American College of Trial Lawyers, and Harvard Law professors as sources for re-shaping the way colleges handle sexual assault going forward. She also mentioned the guidance of two female prosecutors who have handled sex crimes.

DeVos also said part of the new guidance would include a better definition of sexual assault for schools. This is important, because the current definition can brand someone a rapist for misreading courtship signals and attempting to kiss a fellow student. This could also stop the current trend of creating victims out of students who aren’t actually victims, but are told they are as part of a political agenda.

“If everything is harassment, then nothing is,” DeVos said. DeVos explained how the current system doesn’t benefit assault survivors, the falsely accused, or schools. Survivors are still mistreated at some schools, and can’t receive justice when a school’s decision to expel an accused student isn’t trusted.

Falsely accused students receive almost no ability to defend themselves, and are treated as rapists by schools, activists, and the media no matter what the evidence shows. And school administrators are terrified of lawsuits and federal investigations. DeVos said one administrator told her he was afraid to even ask for simple advice from OCR for fear of being investigated and maligned in the media.

We Can Also Set Up More Bureaucracies

DeVos suggested schools try something different when adjudicating sexual assault, and gave the example of a regional center that would handle such claims. The center would work with schools who opted in to the program and would be staffed by experts and professionals who knew how to investigate properly and collect evidence.

DeVos will receive much criticism for her speech today. Most of it will be hysterical claims from activists who appear to believe the Dear Colleague letter was an actual law and think due process is an impediment to justice (a frightening belief). Rather than react with more hysteria, one should really consider what it would mean to continue with mob rule on college campuses, and the effects such a removal of due process would have on the actual criminal justice system.

Here’s why: if today’s activists think due process is so terrible, what would stop them from working to remove it from our courts?