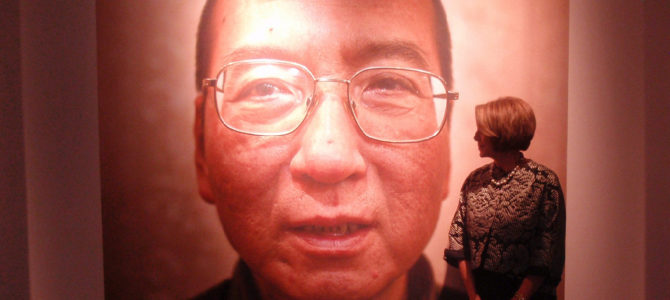

Chinese authorities accuse dying Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo of being one of the most dangerous enemies of the state. Yet Liu’s recently leaked picture shows him staring back, very thin and fragile, with a gentle smile. His glasses gave him a bookish look. You probably can’t help wondering: what could make this seemingly harmless man public enemy number one in China? His “crime”: believing in exercising his human right to free speech. That’s a dangerous thing in China.

Before he became a political dissident, Liu was a scholar and a teacher. He was among the first generation of Chinese youth to take the national college entrance exam and attend universities following the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). After he received a PhD in literature from Beijing Normal University, he became a teacher at the same university.

Besides teaching, he was known to offer sharp opinions that challenged government-sanctioned doctrines and ideology through his many published literature critique pieces. Thus he was nicknamed a “dark horse.” Liu didn’t considered himself a radical, though. In his words, he determined instead merely that, “whether as a person or as a writer, I would lead a life of honesty, responsibility, and dignity.”

He Sacrificed Himself for His Country

The decade from 1980 to 1989 was probably the most liberal period in China’s history since the founding of communist China in 1949. China implemented a series of economic and political reforms under pragmatic political leaders, from Deng Xiaoping and Hu Yaobang to Zhao Zhiyang. A group of Chinese intellectuals encouraged by the relatively relaxed political atmosphere, including Liu, explicitly advocated that China learn from Western civilization: rule of law, free and open markets, and more personal freedom. Liu was a rising star among them, but he wasn’t the most famous.

The year 1989 began as a relatively uneventful year until Hu Yaobang’s unexpected passing in April. Coincidentally, he died right around the Qingming holiday, a traditional Chinese holiday when people pay tribute to their deceased loved ones. Hu was regarded as a liberal hero in China. Many ordinary Chinese people took to the streets to pay tribute for Hu’s death. Gradually, mourning for Hu turned into a movement calling on the Chinese government to grant people more freedom and to apply meaningful anticorruption measures. Peaceful demonstrators, mostly students, started occupying Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

At this time, Liu was a visiting scholar in the United States. He could have stayed here, advocating for freedom and democracy in safety and comfort. Yet he chose to return to China and join the movement, knowingly putting himself in life-threatening danger. By doing so, he followed a long line of intellectuals throughout China’s 2,000-year history who aspired to become “Junzi”—virtuous men who are driven by responsibility to their country and to “Tianxia” (the world). They believed that it’s their responsibility as well as a symbol of their virtue to sacrifice themselves to make their country better.

The rest was history. On June 4, 1989, China’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping ordered the Chinese military to forcefully take back Tiananmen Square and “remove” protestors. The crackdown resulted in an unknown number of deaths of the innocent. June 4 was a turning point for China as well as for Liu. He lost his teaching position and “was thrown into prison for ‘the crime of counter‑revolutionary propaganda and incitement.’”

In Liu’s own words, “Merely for publishing different political views and taking part in a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his lectern, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual lost the opportunity to give talks publicly. This is a tragedy, both for me personally and for a China that has already seen thirty years of ‘Reform and Opening Up.’”

Repression Led to International Acclaim

Since 1989, Chinese authorities have punished Liu for his various pro-democracy activities by putting him in prison several times. In 2008, modeled after Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, Liu co-authored Charter 08, a manifesto calling for Chinese government to implement things Americans have taken for granted, such as freedom of expression, an independent judiciary, and freedom of association. Liu was promptly arrested and later sentenced to 11 years in prison. He has been in prison ever since.

What China didn’t expect was that its repression probably helped turn Liu into an internationally renowned political activist. In 2010, Norway’s Nobel committee awarded Liu the Nobel Peace Prize. Beijing was so furious, it froze diplomatic ties with Norway and heavily censored any Nobel-related news that year.

Liu was the first Chinese citizen to win a Nobel Prize, but he wasn’t allowed to claim it and his wife has since been put under house arrest. The picture of an empty chair representing him at the Nobel Prize ceremony is as iconic an image as the photo of the “tank man.” Both symbolize the Chinese people’s struggle for freedom.

The Nobel Peace Prize vindicated Liu’s moral and mortal bravery. Unfortunately it probably also sealed his fate, because Chinese authorities will never let Liu leave China after he gained such international fame. Recently Liu is reported to suffer from late-stage liver cancer but Chinese authorities are refusing to let Liu seek treatment abroad.

‘Hatred Can Rot a Nation’

China has made great strides in economic development. Internationally, China has used its newfound wealth and power to buy the silence of human rights critics. Many countries who are eager to profit from the world’s second-largest economy have complied by looking the other way. Within China, partly due to Chinese government’s censorship and partly by choice, Liu disappeared from many Chinese people’s collective memory. Most young people who were born after 1989 don’t even know who he is.

The news of Liu’s illness has renewed people’s interest in him and brought back discussions of his work, his struggle, and the part of China’s history that the government still eagerly suppresses. Liu’s ailing picture has cast a long shadow on China’s painstakingly crafted image of a benevolent and progressive global leader. Liu said before that he hoped he “will be the last victim of China’s endless literary inquisitions and that from now on no one will be incriminated because of speech.” Unfortunately, Liu won’t be China’s last sacrificial lamb. China today is less free than back in the 1980s, and the fight for freedom goes on, only becoming more difficult.

Confucius said “Wisdom, compassion, and courage are the three universally recognized moral qualities of a Junzi (virtuous man).” Liu certainly lives up to that high standard. He paid a high price for what he believes in, but he is never bitter. When he last had a chance to communicate to the outside world, he titled his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, read by Liv Ullmann, “I have no enemies.”

While maintaining his innocence and that the charges against him are unconstitutional, Liu gave sincere praise to almost everyone he encountered: policemen, prosecutors, and jailers. He did so not as a grandstanding gesture, but because he believes “Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. That is why I hope to be able to transcend my personal experiences as I look upon our nation’s development and social change, to counter the regime’s hostility with utmost goodwill, and to dispel hatred with love.”

Since the Chinese authorities won’t let the 61-year-old Liu leave China for medical help, he probably won’t have much time left on this earth. But his effort to dispel hatred with love and to never give up speaking the truth has been and will continue to inspire generations to come. “History never really says goodbye. History says, ‘See you later.’” Chinese people probably have a long way to go before they can speak their minds freely without worrying about government persecution. When that day finally arrives, they will remember the name Liu Xiaobo.