Contemporary wisdom suggests that being an extremist is prima facie evidence that you have bad viewpoints, and, very likely, are a bad person. The charge, of course, has had profound resonance in the protracted War on Terror, but has become an ideological bludgeon in domestic politics, as well.

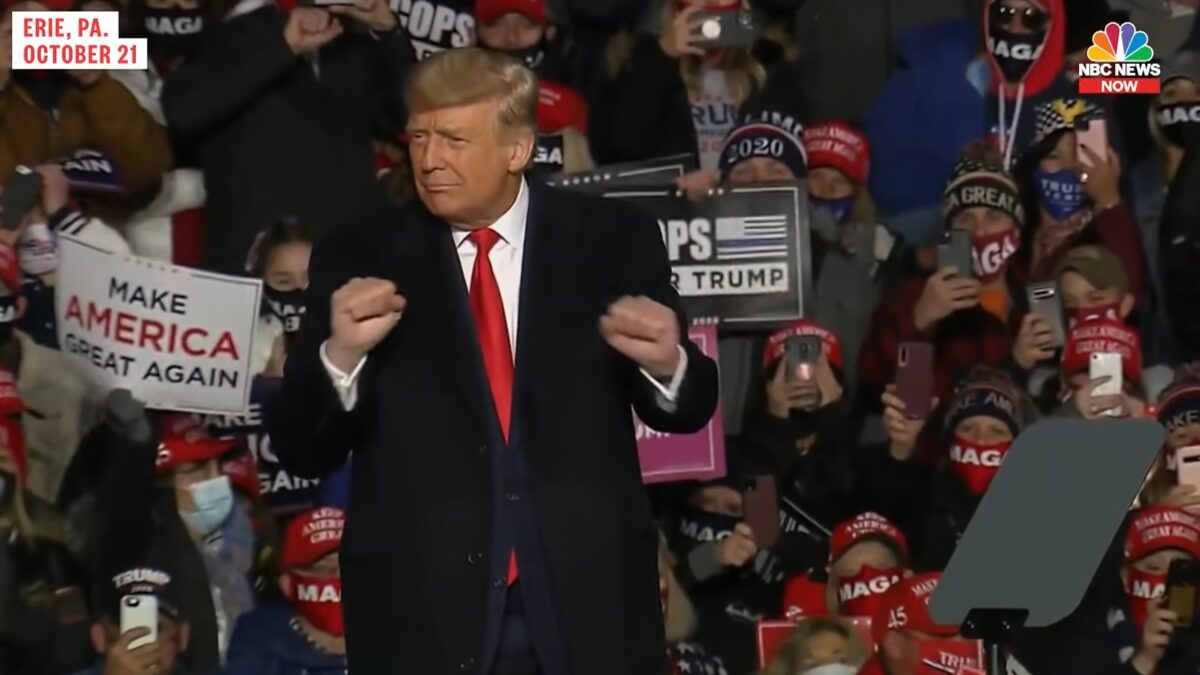

The attack comes primarily from the Left (the Republican Party has long been painted as “extremist”) but the Right often indulges, too. The result? House Speaker Paul Ryan (R) is an extremist, as are Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D), Sen. Mitch McConnell (R), and Democratic Party Chairman Tom Perez (D), who all pale in relation to the big-league master of extremism himself, President Donald Trump (R?).

But what does it mean to be an extremist? If it is accurate to call both conservative Ryan and progressive Warren extremists, does that mean the right thing to do is to average out their ideological differences?

It Sounds High-Minded

It is a noble-sounding proposition, and has motivated political advocacy groups like Third Way and No Labels to champion centrism as a solution to gridlock. Indeed, the idea of centrism in the form of the “Golden Mean” goes back at least as far as Aristotle. The idea is simple but powerful: take two extremes, find the middle point between them that best suits the circumstances, and you get the good and the just.

So, for example, Aristotle defines courage as the mean between cowardice (avoiding all conflict) and brashness (deliberately seeking conflict), or generosity as the mean between stinginess (not sharing any of one’s wealth) and liberality (carelessly giving away one’s wealth), or ambition as the mean between sloth (being lazy) and greed (showing an excessive desire to attain wealth, power, reputation, etc.). This also goes for Aristotle’s understanding of justice: being just requires constantly balancing one’s own good in relation to the common good.

This is ethics 101, but it may sound like a radically fresh idea in these times. What if all our politicians (and the rest of us) really did employ the Golden Mean—instead of individual, party, or group interests—to determine policy positions? It sounds like a good recipe to avoid extremism in everything from immigration, to guns, taxes, abortion, education, and health care.

Stuck in the Middle Without a Clue

Yes, it can be helpful idea. But it’s also a misleading one, and the problem lies in the idea of the “mean” or “center” itself. Embracing centrism as one’s ideological foundation is, in reality, to embrace a moral position that is a case study in circular reasoning. It comes down to making the following argument: “We should embrace centrism because it avoids extremism, and we should avoid extremism because it is not centrist.”

The problem is that this set of claims tells us nothing about why either avoiding extremism or embracing centrism is good; it only tells us about the relationship between centrism and extremism, which we can see more clearly if we express the argument in a non-circular way:

Extremism is bad.

Centrism prevents extremism.

We all should do what prevents the bad.

Therefore, we should all be centrists.

Again, this argument is completely meaningless without knowing why extremism violates the good in the first place. And to know what the good is we cannot just say “it’s the center”; that not only makes the argument circular again, it also overlooks the fact that “the center” is a relational term by definition. The question is: in relation to what?

The Most Important Values Don’t Exist on a Sliding Scale

This point was not lost on Aristotle. The reason he develops the concept of the Golden Mean in the first place is because he believes it is the right way for human beings to pursue and attain the ultimate good, which he defines as a life of contemplation of the Unmoved Mover. In other words, the Golden Mean, or centrism, is a tool for pursuing and obtaining the good—not the definition of the good itself. You cannot know whether to tack left or right unless you have a fixed point towards which you are navigating.

The whole notion of “extremism,” therefore, points to a broader question of what defines the good itself. This question unavoidably implies answers that fit into “either/or” categories, not categories of degrees. Think, for example, of these foundational philosophical questions that have profound political implications:

- Is there a universal morality?

- Is there a fixed human nature?

- Does human life have inherent value?

- Are humans free at all to pursue the good life, no matter how it is defined?

- Is there a reality that transcends the material universe that makes a claim on human beings?

The defining feature of these and related questions is that they can only be answered by a yes or a no. Claiming that morality is pretty much universal, or that human nature is both completely socially constructed and a feature of natural law, or that there is sometimes inherent value in human life depending on the circumstances, or that humans are sometimes always free to pursue the good, or that a transcendent reality does exist from time to time conditional on gross domestic product and employment forecasts, may sound like a beautiful centrist compromise. But it is also nonsense.

Self-identified skeptics don’t get off, either. To say “We can’t know the answers to these questions and so therefore I don’t have to respond to them” is to admit two things: a) you do know that you don’t know, and, presumably, b) you do know why you don’t know, which means, in turn, that you do believe in something universal after all, if only the methodology you’ve used to arrive at the conclusion “I don’t know”—a methodology that has implications for your understanding of the nature of morality, human nature, human life, and the transcendent.

We Are All Extremists! Now Please Resume the Debate

This is all a roundabout way of recognizing that every last one of us cannot avoid living according to some kind of fixed truth. There are some questions we cannot not answer, and the answers we give must come in the form of either a firm yes or a firm no. Thus, if being an extremist means adhering inflexibly to some basic belief or set of beliefs independently of circumstances, then we are all extremists.

To be sure, we can change our answers over time, moving from a no to a yes or a yes to a no and maybe back again; but at any given point we cannot help but be uncompromising about what we believe. No amount of centrism, difference-splitting, averaging out, or triangulation can alter that existential fact.

There is, in the end, a silver lining to putting the Golden Mean in its proper place: if we are all, in fact, extremists with regards to our fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality and the nature of the good, then perhaps we can all agree to drop the term “extremism” from our political vocabulary, or at least use it much more selectively. We should all recognize there is something awry when the same word to denounce ISIS is used to describe a senator’s views on investment tax rates.

Since we still need language to express our disagreement with each other, let me suggest an alternative. Instead of calling our ideological opponents “extreme,” why don’t we just say they are “wrong”—that is, why don’t we say they are making claims about the good of the country, state, community, or individual, that are untrue, or not as true as they should be, then seek to demonstrate what the true truth is?

That might not mend our fractured populace. But at least we’d have clarity on what we are actually arguing about, which itself would mark enormous progress.