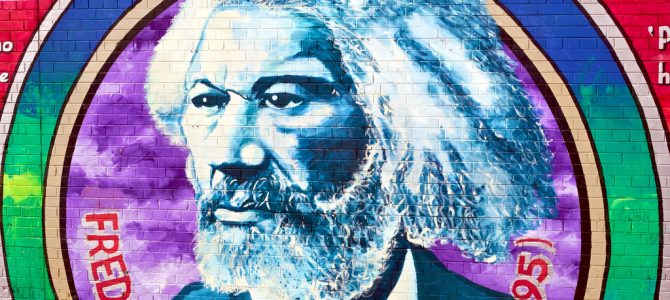

Besides February being Black History Month, on February 14 we commemorate the birthday of perhaps the greatest of all black Americans, Frederick Douglass, founding father of the long black freedom struggle in the United States. So President Trump noticed Douglass in a recent BHM event, and the Washington Post published a commemorative article authored by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and John Stauffer, two well-known and highly accomplished Harvard University professors.

Contributing to a Post series dedicated to challenging prevailing myths, the authors set out to dispel a few prevailing or emerging myths about the great agitator. Those purported myths are of uneven importance, but in at least two instances, the political stakes are high. In pressing their claims, the authors themselves are guilty of mythologizing.

The attempted exposure of “Myth No. 3: Douglass, a Republican, would fit in with today’s GOP,” seems a relatively transparent attempt to claim Douglass on behalf of today’s Democratic Party and the progressive left that dominates it. That claim begs for a rebuttal, but the rebuttal must await another occasion. More important than Douglass’s partisanship is the question of his patriotism.

Questioning Douglass’s Patriotism

“Myth No. 1” in the authors’ lineup is “Frederick Douglass was an American patriot.” Crafting their words carefully, Gates and Stauffer claim it is not so: “Douglass never defined himself as an American patriot.” They provide what might seem the conclusive evidence of Douglass’s own words: “I have no love for America … I have no patriotism. I have no country.”

That evidence is anything but conclusive. The story of Douglass’s American patriotism is complicated and inspiring, and it deserves a much fuller and fairer telling than it receives in the Post article.

Patriotism, Douglass believed, is not the highest of human virtues, but it is a normal component of a morally excellent life. As a general rule, he maintained, one “who cares nothing for the character and credit of his country, will care about as little for his own character and credit.” The sentiment of patriotism “is pure, natural, and noble.”

To say that patriotism is natural is not to say it is indestructible. Douglass worried that despite their generally exemplary record of loyalty and service amid the most trying circumstances, black Americans’ patriotism was gravely endangered by continued subjection to injustice, much of it publicly sanctioned. His confessions that he harbored no patriotism, as quoted by Gates and Stauffer, came of his own experience in slavery. His patriotism, he remarked, had been “whipt out of me long since by the lash of the American soul-drivers.”

Douglass said those things, however, in the late 1840s—still in the early phase of his career, when his thinking was influenced by the radical abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, whose antinomian zeal in some respects skirted anti-Americanism. Garrison rejected the Constitution as a pro-slavery “covenant with death,” publicly burned a copy of it at a July 4 gathering, and called for non-slaveholding states to sever their association with slaveholders by seceding from the federal union.

Given the circumstances of his youth, it is unremarkable that Douglass would first embrace a teaching such as Garrison’s. What is truly remarkable—and strikingly unremarked by our authors in the Post article—is that within a few years, by conscientious study and reflection, Douglass acquired a strong and proud American patriotism that he would retain for the rest of his life.

Frederick Douglass Loved America and Its Founders

Douglass loved America. He loved it for its principles and for its promise. In an 1852 speech on the meaning of July Fourth, a speech now widely regarded as the greatest of all abolitionist speeches, he extolled the American Founders for their courage and wisdom: “They were brave men. They were great men too…. They seized upon eternal principles, and set a glorious example in their defense. Mark them!”

Douglass loved America foremost for its founding principles. He told a New York audience on July 4, 1862, “No people ever entered upon the pathway of nations, with higher and grander ideas of justice, liberty and humanity than ourselves.” The Declaration was for Douglass “that glorious document which can never be referred to too often,” whose “sublime and glorious truths” represent nothing less than “the eternal laws of the moral universe.” Likewise, and in stark contrast to Garrison, he extolled the Constitution as “a glorious liberty document.”

It should go without saying that Douglass was always acutely mindful of the disparity between American principles and American practice in race relations. Even so, he embraced the country for its promise along with its principles. At one of the bleakest moments of what seemed to many the bleakest of all decades for the antislavery cause, the 1850s, Douglass declared that he knew of “no soil better adapted to the growth of reform than American soil.”

With the enactment of the Reconstruction Amendments, Douglass found still stronger grounds for allegiance and hopefulness. Where else in the world, he demanded of an audience of black New Englanders in 1872, “is there a citizenship so desirable, so exalted, endowed with more sublime attributes than the citizenship of the United States? Nowhere.”

Black and White Americans Share a ‘Common Destiny’

As evidence for their claim that Douglass lacked patriotism, Gates and Stauffer also note his expression of interest in emigration to Haiti in 1860. They fail to divulge that this interest appears as a singular and momentary expression of frustration, properly understood in the context of his career-long opposition to all proposals for the expatriation or emigration of black Americans.

Against white colonizationists and black emigrationists, Douglass insisted that blacks and whites in this country share a “common destiny” as Americans, and acceptance of that destiny on the part of blacks should be—and was—much more than a submission to inescapable necessity. In 1851, seeking to combat the alienating effect of the recently enacted Fugitive Slave Law, he declared, “we are anchored to the land of our birth, by the very strongest ties of affection and honor.”

In one of his last great speeches, “Lessons of the Hour” (1894), Douglass provided his deepest explanation of the moral importance of patriotism as he iterated once more his opposition to emigration. “Every man who thinks at all,” he observed, “must know that home is the fountain head, the inspiration, the foundation and main support, not only of all social virtue but of all motives to human progress, and that no people can prosper, or amount to much, unless they have a home, or the hope of a home.”

To have a home, in Douglass’s enlarged, Burkean understanding, is to have a relation to past and future, to causes larger than the self and its momentary gratifications. It is to have a heritage to honor and a legacy to build and bequeath. Home supplies the foundation and motivation upon which human beings improve themselves, their society, even their civilization. And “to have a home,” Douglass emphasized, one “must have a country.”

To cultivate the sentiment of American patriotism was for black Americans in particular a moral imperative, Douglass believed, not least because it was a dictate of interest. Patriotism would assist them both in gaining citizenship and in making the most advantageous use of it. It constituted for them a crucial condition of social and political advancement.

Profoundly patriotic himself, Douglass was no less profoundly committed to spreading and deepening an enlightened patriotism in the minds and hearts of all Americans. He stood in determined opposition to all who would corrode that sentiment, whether by government-sanctioned injustice or seductive and alienating appeals to sentiments of racial identity and racial nationalism.

It seems sadly telling of the present condition of the American academy, and perhaps also of our national politics, that two of the academy’s brightest stars—I say without a trace of irony about two scholars of genuinely outstanding ability and accomplishment—would think that they do honor to Frederick Douglass, on the occasion of his birthday, by cleansing him of the taint of American patriotism. To correct the record is a political no less than an intellectual imperative.