As a little girl, I once asked the McDonald’s cashier for a Hot Wheels instead of a Barbie toy in my Happy Meal. The cashier responded with something like “But that is a boy’s toy.” My mother looked right at me and snapped: “Don’t you ever let someone tell you that you can’t have something because you are a girl.”

I believed her. I truly believed my “girlness” was not a disability or a limit. I grew up thankful for the feminists who came before me, for paving a way for me to vote, work, go to college, own property, run for office, etc.

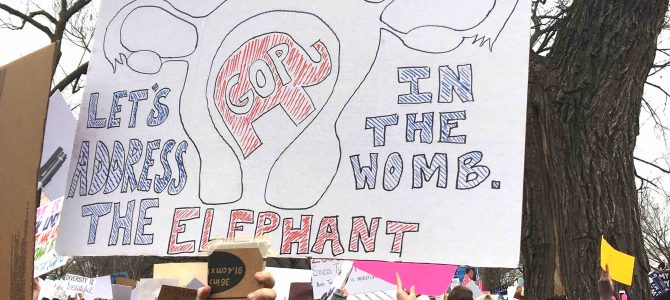

But now, here I am 25 years later, and I have spent most of my adult life deeply struggling with the idea of identifying with the feminist movement. This struggle has taken many forms, but with the recent Women’s March on Washington many feminists helped end my struggle as they told me where I belong in the movement.

A march of such a name suggests that it represents the perspective, desires, and good of all women. But after reading their Unity Principles, I felt completely excluded. These are not principles of womanliness, these are principles of progressive Democrats. With the added controversy surrounding pro-life feminist groups who wished to partner with the march, it was clear the leaders believe there isn’t room for disagreement.

The title of the march coupled with these principles suggests that each and every woman should come to the same political conclusions, otherwise they forsake their own womanhood and that of their sisters. But I just cannot believe this is necessarily true. I cannot understand how my sex is so determinative that it must cause me to conform on issues such as environmentalism. I am a woman, but that shouldn’t limit me to one dictated worldview.

Empowerment, Or Every Woman in Her Place?

Many women have raised their voices in disagreement with the march’s methods, ideology, or cause, only to be put “back in their place” by other “more feminist” women. This public dialogue brings to the forefront the toxicity of the feminist movement as it stands today. Many women writers have taken the opportunity to offer a strong, positive voice on the subject. For example, this article recently published on The Mirror reflects beautifully on women’s empowerment.

But other women, in the name of feminism, insist such empowerment is only the luck of one’s time and place at best, and likely completely a delusion. Even if you feel empowered, you are not—and you need the women at the Women’s March to protect you.

Dina Leygerman’s article, “You Are Not Equal. I’m Sorry,” epitomizes this idea. She is responding to another popular post expressing dissent to the Women’s March. Leygerman insists that even the confident, empowered woman is actually “wrapped up in [her] delusion of equality.”

After scolding other women for not being thankful enough for their equality, she explains how unequal such women really are. It’s mostly because society has yet to treat them like men. Using a smattering of unconnected feminist rally cries, she belittles women, their bodies, their reproductive systems, and their work.

Even when she does manage to identify a legitimate injustice (such as wives being beat by their husbands), she fails to identify the solution. Whatever the solution to domestic abuse and the legitimate objectification of women, it is not marching on Washington with pussy hats on our heads. This only reinforces our objectification.

Aside from the sloppy argument, the most offensive thing about Leygerman’s article is her tone. With a righteous shrillness she sanctimoniously puts confident women back in their place, all in the name of feminism: “Open your eyes. Open them wide. Because I’m here to tell you, along with millions of other women that you are not equal. Our equality is an illusion. A feel-good sleight of hand. A trick of the mind. I’m sorry to tell you, but you are not equal. And neither are your daughters.”

Leygerman’s tone and argument are a problem. Women should not be limited to just one ideology or identity, and women should not be made to feel less than human because of our sex. In an attempt to open the eyes of the oppressed to their oppression, Leygerman actually participates in the problem as an oppressor.

So what is the other option? Instead of using the public voice given to us by our foremothers to scream about “unmentionables,” why don’t we take the opportunity to open the dialogue to something bigger? As we examine womanhood within its context of civil society we should seek to understand the woman in the context of her humanity.

Our Diversity of Identity

Women can offer more to public discourse than pussy hats and pictures of sexual organs. We make up more than half the population. We offer diverse opinions, perspectives, life experiences, intellectual gifts, emotional gifts, and backgrounds. Yet modern feminism rejects many empowered women—and for what end? Ultimately, I fear that reducing us to one voter bloc with one homogeneous opinion will damage the beautiful diversity that is womanhood, and ultimately humanity.

Not only do I identify as a woman, but I also have a number of other titles that could be used to label my identity. These other identities, as much or more than my sex, guide what I want, desire, and work toward. These are identities developed by my education, religion, family, job, marital status, hometown, and community. Such identities inform my actions and beliefs. They even inform my “womanhood.” But I have been consistently told many of these beliefs and identities are incompatible with my responsibility as a woman to perpetuate feminism, even if these identities empower women.

This is where I fear modern feminism has gone awry. We have stopped gazing on the ends and are focusing our attention only on the means. The end is a virtuous civil society. The necessary means is supposedly feminism. This shifts the focus to identity of those associated with the issue instead of the humanity of the people the movement is trying to save.

This also forces an unnecessary perpetuation of the movement. If a well-ordered civil society has been established, women do not need feminism. This is dangerous, as such a movement may never be laid to rest, even when it has accomplished its end.

Now, to be charitable, feminism is rooted in some understanding of the virtues of justice and equality. At its core, I have been told, feminism is “the radical idea that women are people too” (although very little of this language seems to be circled on social media or protest signs from the walk). If this is true, then feminism must work to understand that entire sentence.

Feminism must work to not only understand women, but to understand people—and, subsequently, what it means to be “people too.” In other words, the conversation about feminism should be about what it means to be a human being.

If this is true, are conservatives really the enemy of feminism? While they might disagree about using government to “equalize” women, it is not inherently conservative to believe that women do not deserve the dignity of personhood. Just look around to know that this isn’t true. Even the most “vile” offenders such as Fox News and the new White House administration are studded with intelligent, strong, conservative women.

Let’s Have Unity through Virtue

So if women are people too, there is room for unity, right? Not necessarily unity in our political opinions or ideology, but unity in our personhood, or shared humanity. I am first a human being, and as a human being I believe I have a responsibility to pursue virtue. This is what we should coalesce around. It provides common ground to then discuss differences towards achieving a good end.

Over the last year, conservatives and liberals alike have forsaken the pursuit of virtue for the sake of political expediency. Public crassness will not protect private virtue. We need a dialogue seeking to know what is virtuous. A society that loves and seeks virtue will be less prone to allowing systematic and flagrant injustice to reign. Such a society will breed gentlemen and cultivate ladies. Such a society will develop humans.

Studying what is virtuous informs our humanity. A society that desires virtue will not be fraught with the plagues of injustice. A society that seeks truth will not undermine women, for such a thing is not true; a society that desires honor cannot allow sexual violence to run rampant, for such a thing is not honorable; and a society that loves what is good cannot deny natural rights to its members, as this is not good.

We cannot rid the world of injustice, because as long as there are humans there are the unjust desires of the heart. But we can, by looking outside of ourselves, live in communities that strive for something beautiful. A community that desires virtue will not stand for systematic injustice and oppression. Instead it will weed out its offenders, protecting its most vulnerable.

So with this, I also humbly ask more of the feminist movement—not just for the sake of womanhood, but for the sake of humanity. Refusing to be limited by my womanhood does not mean that we cannot be empowered by the things that make us distinctly woman. I want to see a full and beautiful understanding of womanliness and a full and beautiful understanding of what it means to be human.

Once we understand that, we can then consider what it means to empower women, and what we want to be empowered to do. To have a “women’s movement”—whatever that means—requires us to first identify as human, then seek virtue, and finally develop a civil society that through virtue supports the human. There we might be able to freely embrace womanliness as beautiful, powerful, and important.