Pasadena, California — While shopping along Raymond Avenue in Old Town Pasadena last week, my friend and I stopped into the Church of Scientology to take a free personality test that was advertised on an A-frame chalkboard sign just outside.

As a Christian, I wasn’t really searching for guidance or salvation, but I wanted to hear the Church of Scientology’s elevator pitch. I wanted to know what they said to make people fork over massive amounts of money, or even distance themselves from family members in an effort to work their way up the church’s ranks.

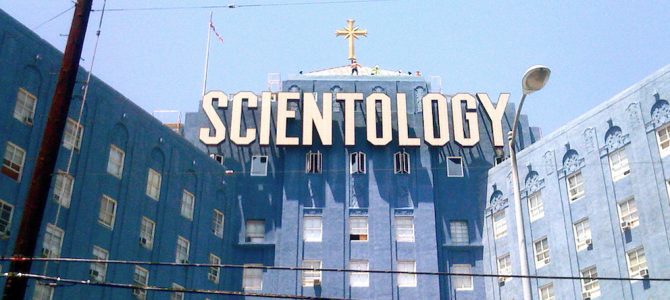

I couldn’t help but notice how luxurious the building was. The church’s visitors center looked like a museum. There were exhibits with many informational panels complete with interactive video screens and elaborate visual props. During our afternoon visit, I noticed there was an indoor fountain, several movie theatre rooms and a coffee shop just in the portions of the building I wandered into.

It’s estimated that about $1.5 billion of the church’s $1.75 billion worth is tied up in real estate holdings worldwide, and some former church members claim that Scientology is nothing more than “a fundraising ploy to buy real estate, to persuade people to give them money.”

Upon entering, my friend and I were greeted by a young man at the front desk named Andrew, who wore a grin that never seemed to escape his face. He explained to us that we should allow an hour to take the Oxford Capacity Analysis developed by the church’s founder, L. Ron. Hubbard. The test would reveal our biggest strengths and weaknesses.

We were given pencils and a scantron-like test as we were guided to an area just beyond the visitors center with rows of desks that were partitioned off.

I took the free personality test at the church of #Scientology. Many of the q’s were to assess if I could”take orders” and “obey” pic.twitter.com/k3iAecSbLB— Bre Payton (@Bre_payton) December 31, 2016

Many of the questions seemed to be aimed at assessing how confident and competent I was.

“Does the idea of talking in front of people make you nervous?”

“Can you ‘start the ball rolling’ at a social gathering?”

Another question further down in the test asked something along the lines of whether I thought my opinion was worth sharing out loud. As someone who is paid to speak my mind, I marked down that I strongly agreed with that statement.

After we finished taking 200-question test, we were told the tests would be graded and our results would be assessed individually. The time between taking the test and having them assessed stretched on longer than I anticipated. Whenever I asked a question, I was directed into another theatre room and presented with another short film. Instead of a direct answer, I was guided to another video presentation or elaborate information display in the visitors center.

Next, my friend and I were led to an E-meter machine, which passes a small amount of electricity through your body in an attempt to read how “strong” a particular thought, memory, or sensation is.

Our tour guide, named Kenny, handed me two can-like objects which were attached to the wires stemming from the E-meter. With my permission, he pinched me, and I watched as the needle on the machine ticked upwards on the screen. He explained this indicates this had a strong reaction in my reactive mind and that I needed to think about it a few more times to bring my experience out of the reactive mind and into the analytical mind.

I was asked to think about the pain again and again until the needle didn’t tick up as high on the reader. He told me that this was because I had rationalized the painful experience and all problems could be rationalized through auditing sessions. You can read a more complete explanation of all this here. When I asked how much these sessions cost, Kenny told me that the cost varied person to person, but that I could buy a package of 12 one-hour sessions for about $120 to start.

After about 45 minutes of videos and the E-meter demonstration, we were finally separated and given our results. Then things took a turn for the weird.

While my friend sat with the aforementioned Andrew, he told her to stop taking her anti-depressants, because she wouldn’t be able to complete the church’s “Dianetics” course unless she was off any prescribed medication for at least 24 hours before taking the initial assessment. Andrew bragged that he had convinced a schizophrenic man the week prior to stop taking medication and to rely on the church instead. He kept pushing Scientology as a cure for mental illness because, he said, it can solve everyone’s problems without “making it up” like therapy and medication.

After she resisted his efforts to sell her Hubbard’s “Dianetics” book, Andrew told my friend that people never come back to the church unless they buy a copy. When my friend responded that she could just buy the book online at a later time, he responded that he was scared of what the Google results would be.

Don’t trust what they say on the Internet, he warned.

He proceeded to ply her with questions about her job and about how much money she earns, before revealing that the church doesn’t pay him well, but that he continues to work for them anyway because he likes to be around people. It’s no secret the church has issues with paying its employees a decent living wage. Members of the church’s Sea Organization are reportedly forced to work for mere slave wages, and when they leave the Sea Org, most do so with little to no money in their pockets.

“I do this because I like to help people,” he said.

Meanwhile, Kenny tried to convince me that I had problem areas in my life. According to the church’s assessment, my thoughts are often dispersed, I’m frequently nervous, and I’m a critical person.

He asked me how I felt about my scores and about myself, and I responded that I felt pretty good. This answer baffled him. But what about these areas in which you scored low? he asked. I told him they didn’t bother me, and his demeanor quickly changed. He seemed to ease up after realizing that I was confident and didn’t see myself as a damaged individual who needed the church’s help.

The stories of the three church employees I met were remarkably similar. All said they had “problems” in their life and came to the church to help work them out. All were poor communicators, according to Hubbard’s test, and had social anxiety. One man told us he dropped out of high school at 17 when he was required to read something aloud in front of his history class. Andrew said he had a speech impediment and stuttered before joining the church, and Kenny told me he scored as low as possible in the communication category and was traumatized from a friendship that turned ugly.

None of the three church employees whom I spoke with at length had an education beyond high school. Our two tour guides both started working for the church at 17 years old and have no other professional experience outside of the church.

All came to the church with low self-esteem and a lack of necessary social skills. The church, its courses, and its auditing sessions gave them the confidence they so desperately lacked, they said. The church’s recruitment methods all seemed to be directed at finding a specific kind of person: someone who was vulnerable, overwhelmed by his or her shortcomings, someone who had poor communication skills, who lacked confidence, and was desperate for help.

The most alarming part of the visit was when I asked Kenny what happens if someone wants to leave the Church of Scientology. He responded that when individuals don’t follow the church’s rules, the church intervenes.

“We don’t force anyone to stay,” he said. “But I could see why people have that idea.”