A would-be summer blockbuster, the Ben-Hur remake disappointed at the box office. CGI chariots and temple facades cost enough that the earnings differential qualifies the film for epic bomb status, as you may have read.

We could presume a dwindling population of devout moviegoers is to blame, but the success of “Passion of the Christ,” for instance, not quite 12 years ago would stand against us. We also can’t claim our culture’s lost its taste for grand spectacle or histories with supernatural underpinnings. The problem might be that “Ben-Hur” didn’t need to be remade, as reviewers suggested. The 1959 adaptation—although dated by its “overture” and “intermission,” and makeup-darkened Levantines—by and large stands the test of time. It’s still thrilling: a chariot race immortalized as a pop-culture reference point; imperial abuse avenged; and, chiefly, salvation witnessed.

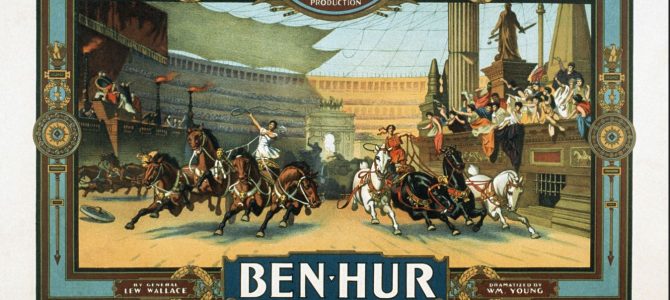

The problem, I’ll venture, wasn’t that the story of “Ben-Hur” is ill-suited for modern audiences or too well-known to be worth re-adapting. Yes, it’s hard to be kept in thrall by a story one already knows, but how many among the target viewership for summer blockbusters (viz., nerdy young men who’ll go to the movies multiple times) actually know the tale of Judah Ben-Hur? Trailers and posters banked on name recognition and chariot imagery to trigger a collective sense of cinematic greatness. Yet the book, “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ” does not, it would seem, ring so many bells these days.

The original novel was a hit on par with “Pilgrim’s Progress”. Published in 1880, it became the bestselling novel of the century, surpassing the mid-century favorite “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” But by 2016—not so surprisingly—it’s been downgraded to “Ben-Huh?” or, at best, “No, but I’ve seen the [1959] movie.” It’s been lost in the enormous and growing library of incredibly famous books no one reads anymore, and edging into that even larger dustier basement library of books everyone read a century ago that now no one’s even heard of.

Being the source material for this summer’s floppiest stink bomb of a movie needn’t seal the novel’s fate, however. Movie remakes may be distressingly common these days, but it’s not nearly as often that books with storied reputations get rewritten for modern audiences, and when they do, it’s usually cause for consternation. Fortunately, author Lew Wallace’s heir Carol Wallace, a top-shelf author in her own right, has seen to its rightful resurrection in a new retelling of “Ben Hur.”

An Immortal Story

Carol Wallace co-authored “The Official Preppy Handbook” and wrote “To Marry An English Lord,” which helped inspire the “Downton Abbey” phenomenon. Most recently she penned a well-received historical novel about Vincent van Gogh. Taken together, her oeuvre holds a strong sense of one’s place in history and a kind and cunning humor. But absent the autobiographical ancestral aspect, an epic such as “Ben-Hur” would fall somewhere beyond this Wallace’s wheelhouse.

Judah Ben-Hur is a Jewish prince captured and enslaved by Roman conquerors in Jerusalem. His sister and mother are taken at the same time. He comes to manhood as a galley slave, a career that for most of his cohort ends in an early death. But our hero survives, and like Moses before him he’s adopted and raised as the son of noble house in an otherwise oppressive culture.

In Carol Wallace’s update, as in Lew Wallace’s original, Ben-Hur is more a man of action than one with a rich internal life. We do understand he frequently worries about his mother and sister, and he burns to avenge their capture against his childhood friend turned Roman tribune Messala. As a grown man five years later, and a keen charioteer it so happens, he returns to Jerusalem where Messala still resides, hardened of heart, and holding down the imperial fort. That’s where the action really kicks off. Meanwhile, a challenge has arisen to Roman authority in the person of Jesus Christ, King of the Jews.

Re-inheriting the cultural legacy of Ben-Hur becomes an intimately personal mission for every Christian, not just for the great-great granddaughter of Lew Wallace. Like translating the Bible, be it the Vulgate, vernacular, or NRSV, the hope is that there’s more to be gained than lost in delivering the content to a broader audience. As the films of 1925, 1959, and 2016 attest, the delivery is but a vessel for an immortal story. In the late fifties, Jewish captives rowing in the underbelly of the Roman vessel brought to mind not-too-distant Nazi death camps.

Those Universal Christian Themes

Carol Wallace writes in an afterword that General Wallace was a Union commander during the Civil War. A controversy over him apparently flubbing orders from General Grant at the Battle of Shiloh, biographers believe, inspired Judah Ben-Hur’s tale of revenge and redemption. Only after decades of dishonor was it found to have been a wrongful accusation.

But more broadly, in his “Ben-Hur,” the path of righteousness and salvation is one we walk with Christ, and Romans’ enslavement of their conquered peoples represents the ultimate in evil. While realism rather than historical epic was the fashion in fiction writing, slavery and redemption were nevertheless hot-button topics of the Reconstruction era, when Lew Wallace was writing.

Circumstantially in the novel, tension and union between a broken humanity and its salvation do suggest memories of the Civil War. But they also hold up those universal Christian themes—forgiveness, redemption, loving thy neighbor to walk with God—that always and everywhere bear remembering. Carol Wallace’s afterword (a wonderful essay, practically worth the price of admission, or the $9.99 on Amazon, as it were) also reveals that while “Lew’s evident faith” may have compelled millions of readers, it was really a lack of evidence that first compelled his writing. He met agnostic orator Robert Ingersoll on a train and had his unexamined faith challenged:

Basically, Ingersoll took Lew apart. Did Lew believe in Christ? Yes. Why? He didn’t know. Had he read the Gospels? Um . . . some of them. Did he really believe in those miracles? Um . . . maybe. Why? Did Lew really believe Jesus had risen from the dead? All that nonsense about Lazarus, three days dead and half-decomposed—how could an educated man believe such a thing?

Lew didn’t know. He didn’t know much, he realized. And his talk with Ingersoll embarrassed him. Faith was a vital issue in those days., and though Lew was no churchgoer, he recognized Christianity was fundamentally important. How could he, an educated, inquiring man, have reached his age without ever giving serious thought to his faith?And then, being Lew Wallace, he decided to look into the issue, which meant writing a book about it.

Perhaps one great virtue of the famous story, then, is that its hero’s conversion is also its author’s. Through writing his christological novel, Lew Wallace found truth in the life of Christ. Whether a reading reveals it, you can be the judge.

‘Ben Hur’ Anew

But thankfully, “Ben-Hur” endures. Here we have it anew, recast for a modern reader. Perfect for a twenty-first-century classroom (although best a parochial one, probably), certainly a Sunday school or confirmation class. Thees and thous redacted, thrills intact.

Read it to revisit a story you already know, or as an introduction to one once wildly popular for good reason. Virginia Woolf wrote at the dawn of the cinema that films would corrupt fiction. Failing to create graceful spaces for interior action, film seals off the imagination, or so Woolf contended.

Whether or not you buy a word of that, and I’d say countless highlights from the last century of cinema prove her wrong, this re-novelization is a wonderful countermeasure. The 1959 Charlton Heston film has overshadowed the original novel in our collective cultural imaginations for the intervening decades. It may be for the best, then—in the best interest of a grateful modern readership’s cultural re-inheritance of a worthy classic—that this summer’s casts a considerably shorter shadow.