Two years ago I chased down a single dad whose son attended schools in the same district as the infamous Missourian Michael Brown. Sixty-six-year-old Paul Davis, a cab driver and son of Mississippi sharecroppers, decided to pay $1,500 in rent atop his mortgage just to get his son Robert out of some of the nation’s most violent schools by establishing residency in a better school district.

Davis told me about the time in fifth grade other black boys had held Robert down until he peed on himself; the time bullies stole his book bag; the many times they attacked Robert—in classrooms, in hallways, in the lunch room.

In middle school Robert, who has mild autism, became a favorite target for bullies because his mom is white and his dad is black, so “he was the lightest kid in the whole school.” Eight days into seventh grade, another boy shoved Robert’s arm between two desks. The teacher called an administrator, who took Robert to the nurse’s room. The nurse wasn’t there, so the administrator sent Robert back to class. And that was the end of it. Davis’s blood boiled.

“You do things wrong, you outta here, and you ain’t coming back,” he said. “That’s what they shoulda been doing in Normandy [School District].”

Robert’s former middle school sounds like a nightmare: “A boy got killed in the lunch room,” Davis told me. The kids were playing a “game” that involved taking turns punching each other as hard as they could. “One kid punched the other in the chest, and the other died. There were no criminal charges at all—they said they was playing…They got what they call in-school suspension, where they go in a room with the other bad kids, because the federal government—whatever way they allocate funds.”

Hide Your Kids, Hide Your Wife

Davis was about to file a federal complaint when a judge ruled that because Robert’s school district had lost its accreditation the children there could transfer to nearby school districts, nearly all of which performed better. The receiving school districts complained so mightily over the next year, however, that the state revoked that option, sending all the Normandy kids back to their still unaccredited schools.

That’s when Paul said “Aw, hell, no,” dipped into his meagre savings, and bought his youngest child a ticket outta Dodge—just in time to avoid the Ferguson riots that began that very summer.

As everyone knows, racial unrest has only increased since then, and is in fact linked with public campuses through gangs, personal relationships, and protest movements. The highly publicized race-related violence in city streets this summer erupted first inside public schools inside many of the same cities, including Baltimore, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and New York City.

Soon before school let out for a boiling hot summer of racial angst, local news reports depicted frightening levels of violence erupting inside the first school systems to implement new federally approved discipline policies. In Milwaukee, for example, teachers reported a spike in aggressive student behavior after the district began reducing its punishments for students to comply with federal guidelines. The stories are insane:

Gilbert Valdes was attacked by a third-grader who was transferred to his school after stabbing a girl in the face with a pencil.

And Jennifer was attacked by a middle schooler who had just pummeled a sub and had been transferred from another school after violent behavior there as well.

That girl had been placed in a special room for students with behavioral problems at Jennifer’s school, but the girl simply walked out, started roaming the hallways, and violently attacked Jennifer and another teacher.

Teachers in the Twin Cities threatened to strike over the levels of school violence they were enduring after their district began phasing in the new federal rules. The trigger incident, which came upon a wave of increased school violence:

a 55-year-old Central High School teacher was choked into unconsciousness after trying to break up a fight that started over an argument about football statistics. When the teacher intervened, a 16-year-old student allegedly picked up the teacher and slammed him into a table and chair, before slamming him to the floor. The teacher passed out for 10 to 20 seconds.

One Milwaukee teacher said a second grader slammed the teacher’s foot in a door and faced no consequences for it: “He was having some sort of emotional breakdown in the hallway and was kicking and slamming his body into the door, which was partially glass. I went out in the hall because the protocol is not to go after students, but I went out in the hall to make sure that, one, he wasn’t going to hurt himself and, two, that he wasn’t going to leave the building because that has happened as well.”

“He was in my classroom the next day,” she told Dan O’Donnell of Milwaukee’s News Talk 1130. “No repercussions. He sat in the office for an hour the day that it happened, but no, nothing happened.”

Thanks for the Ratchet, Feds

“Other teachers say that this is a common practice in their schools: Students will be issued a referral for misconduct and then ‘counseled’ before being returned to class without being formally disciplined,” O’Donnell reports. Why? Two levers the federal government is pulling, both related to school districts’ discipline numbers.

First, inside the Every Student Succeeds Act, which House Speaker Paul Ryan recently sped through Congress to replace No Child Left Behind, the federal government now includes measures besides test scores—such as annual suspension and expulsion rates—in ratings that influence funds and federal probes. Schools are technically supposed to report to the federal government every disciplinary action they take, and now they have more reasons to juice the numbers.

Second, back in 2011 former Education Secretary Arne Duncan and former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder told schools that consequences for bad behavior, not the behavior itself, was to blame for the “school to prison pipeline.” In 2014 the pair issued regulations telling schools they would be liable for federal investigation if they recorded data showing black or Latino students had committed more infractions than white or Asian students.

“Schools also violate Federal law when they evenhandedly implement facially neutral policies and practices that, although not adopted with the intent to discriminate, nonetheless have an unjustified effect of discriminating against students on the basis of race,” their subordinates wrote in a “Dear Colleague” letter (emphasis added).

Catch that? If schools have rules that apply equally to everyone, but it just so happens that more students of one race break those rules more than students of another race do, the federal government will consider that rule racist and could prosecute the school. This even though, as Jane Robbins summarizes, research shows “racial disparities in discipline result from differences in student conduct, not from racism.” This means these school discipline rules are likely to increase, not reduce, racism.

“Socioeconomic factors such as family income and childhood stress are some of the best predictors of student behavioral problems, and since variations in those influences are not evenly distributed by race, schools will have to engage in racial discrimination when meting out punishments,” wrote University of Colorado-Colorado Springs associate professor Joshua Dunn. “The victims will not be limited to unfairly punished students. All students who come to school to learn will have their education disrupted by troublemakers. In urban districts, those motivated learners will be primarily students of color.”

Now For Ineffective Kumbaya Circle Time

In response to these federal rules, states including Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Minnesota, California, and Washington have declared they will remove fewer violent students from classrooms through suspensions and expulsions.Children are not stupid. They have figured out that they can terrorize their peers and authority figures and get away with it now.

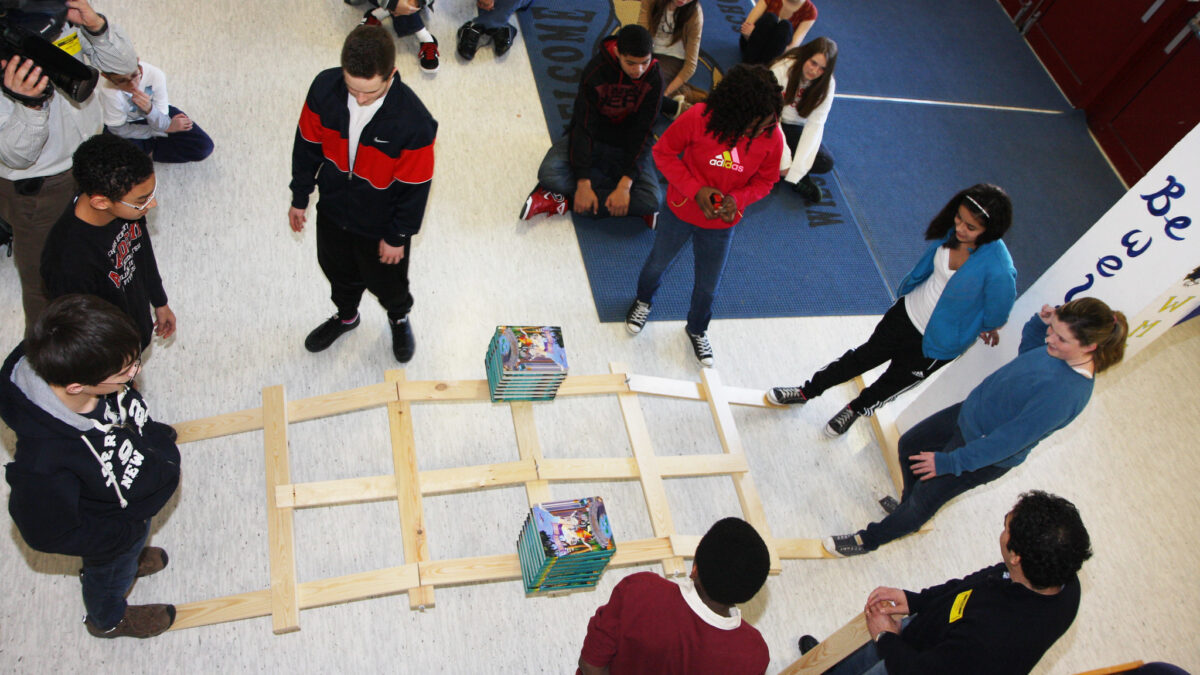

Schools are replacing stricter consequences with touchy-feely therapy sessions for troubled kids, which are less of a deterrent to bad behavior and often explicitly excuse it. The Wall Street Journal recently reported on one such program inside New York City schools:

One afternoon earlier this month, several students sat with three school safety agents. They spent three hours talking about prejudices based on hairstyle, neighborhood and background, and doing role-play exercises to understand each other’s views.

As a result of substituting these techniques for removing problem students from classrooms, citywide suspensions fell to 44,626 in 2014-15 from 69,643 in 2011-12, the Journal reports: “The past year’s citywide drop is largely due to the disciplinary code that took effect in April 2015, requiring principals to get approval from the education department before suspending students for defiance or insubordination.”

While these numbers will help keep the feds off administrators’ backs, it’s not clear they’re improving classroom safety. A report from an independent parents’ group using state data concludes New York City schools saw more violent incidents in 2014-15 than in 2011-12; even the city’s data shows that 2014-15 in-school violence roughly equaled that of the year previous.

Since Indianapolis began a similar program in an effort to reduce suspensions for unruly students, classrooms and hallways have gotten more violent, a teacher told Chalkbeat Indiana this spring: “Without that threat [of suspension], he said, there were five fights in the hall outside his classroom during the first half of this year.” The same happened when Los Angeles schools implemented “restorative justice” programs in an attempt to get their suspension numbers down to keep the feds off their backs: “Where is the justice for the students who want to learn?,” asked eighth grade math teacher Michael Lam in a public meeting.

A Baltimore Public Schools teacher who asked me not to use her name for fear of losing her job has sent me several videos of students backtalking, ignoring her instructions, and acting aggressively in class. School discipline tactics are just a management tool, she noted; the root problem is students’ parents and homes, which nobody will discuss for fear of being called racists.

She and her colleagues hardly know what to do because: “There’s nothing the administration can do about it because you can’t suspend anybody, you can’t give detentions to anybody, and parents don’t care so you can’t call them…If you call a home parents are very likely to tell you [that] you are a racist. It used to hurt me, but now I say ‘98 percent of my kids are black, and I’m just being racist against your kid?’”

Let’s Aim Tanks At Misbehaving Kids?

While school staff are often victims of student violence, school officials aren’t innocent of contributing to these problems, typically with cowardice. School officials are afraid of federal sanction, career-ending accusations of racism (however spurious), and out-of-control students. Sometimes they also respond by gearing up. Like local police and also thanks to federal programs, school safety patrols are militarizing themselves.

This is again directly related to bad federal policy: a recent Huffington Post investigation found that a Bill Clinton-era federal program has pumped $867 million into increasing the presence of police in schools. “In 1997, the Department of Education reported that law enforcement officers were present in 10 percent of public schools at least once per week. By 2014, 30 percent of public schools had school resource officers, or SROs, the most common type of law enforcement on campuses.”

This is a classic cycle of violence: Initial bad behavior leads to overreaction which prompts a corresponding overreaction, and so on. It’s less important here who started it than it is that we stop the cycle. Besides, there’s plenty of blame to go around. Yes, far too many families have enabled and even encouraged dangerous behavior. Yet the proper response is not running away from those angry little children in fear nor running toward them only with handcuffs. Neither is it preventing schools from enforcing basic rules of conduct that allow every willing child to actually learn in peace.

Seven in ten Americans oppose the Obama administration’s racial quotas for school discipline. Majorities of Republicans, Democrats, blacks, and Hispanics oppose that policy (and black support switched between 2015 and 2016, from 65 percent support to 48 percent support). This should be low-hanging fruit to chop off and consign to the dustbin.

After that, there is a big debate about what to do with violent kids besides treating them like either criminals or misunderstood victims. Kids who act badly are neither. They are people just like the rest of us, who need to learn to own up to their bad choices and practice making better ones. While various schools attempt to figure this out, however, the rest of us can do two things. First, refuse to engage in the bigotry of low expectations by saying kids of certain races can’t be expected to treat their fellow humans well. Second, the most effective way to provide an immediate escape hatch for desperate families like the Davises is the thing that saved Robert Davis in the first place: taxpayer-funded school choice.

“I thank God for those Supreme Court judges who made that ruling” that allowed Robert to transfer to better schools, Paul Davis told me. “It not only changed me and Robert’s life, it changed other kids’ lives. Two thousand kids transferred at the same time—1,100 from our school district alone. That’s a lot of people.”

“I tell [Robert], ‘My happiness counts on you being happy.’ And it’s all of our responsibility. We all God’s children,” he said later in our conversation. “I’ve been a taxi driver for 22 years, and in those 22 years I’ve seen a lot of life. The one thing I see with the world today is children are not being kept safe. It’s hard to do better if you don’t know better. It creates a cycle. Until something happens to break the cycle, it continues.”