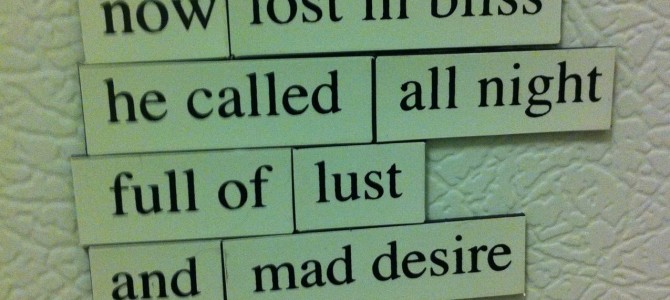

Think of poetry as a room for rent. The walls are bare, the lights don’t work, and there are scratches on the floor from the last owner’s dining room table. But as a blank canvas for the imagination, the space is wide open.

For Ben Lerner, poetry is prime real estate, and in The Hatred of Poetry, the poet and novelist acts as a personable salesman, taking readers on an evening tour through the poetics of potential, and opening a window to a realm beyond mere words.

Lerner’s slim, 80-page sales pitch is a defense for an art that is often dismissed in favor of more flashy, fully-furnished forms of entertainment. Though poetry often fails to live up to lofty expectations, flawed wordsmiths and architects cannot blame the empty room itself; words only create the “space for the genuine” that is the essence of poetry. Poetry is both possibility and impossibility, Lerner says, and readers are tempted to buy it.

“It’s not much,” says Lerner as readers peek around the door frame, echoing Marianne Moore’s famous poem-hating poem of the same name: “I, too, dislike it.”

The Fatal Problem With Poetry

Lerner’s style of salesmanship is unhurried, conciliatory, and discursive; he begins by telling the story of the first time he crossed the threshold of poetry in elementary school.

For young Lerner, as for many readers, poetry seemed like a locked door—exclusive, complicated, hard to understand. Lerner claims that much of people’s hatred of poetry is either fear or disappointment, stemming from an uneasy sense that poetry is a type of speech intended to be lofty and meaningful. But behind that tantalizing door is just another dusty apartment, abandoned by beauty. Readers turn from their early explorations with “perfect contempt” for the art (another quotable tidbit from Moore’s poem)—and rightfully so.

Or maybe, one could argue, poetry-haters just don’t like poetry.

Still, regardless of taste or experience, readers’ responses to poetry reveal that they hold it to a higher standard than other speech. Poetry is supposed to touch people and point to some larger meaning. More often, it leaves them shut out in the cold.

Lerner proves himself a masterful marketer by giving in to these arguments completely, acknowledging the flaws of “an art hated from without and within.” Then the subtle salesman shows readers around the room and unfolds his vision, transforming the space with a theory of poetry that is as simple as it is paradoxical: “The fatal problem with poetry: poems.”

He begins right where the haters left off: with the shabbiness of the room. The distance between readers’ expectations for poetry and their disappointing experience of it sets up a divide between the “virtual” and the “actual.” Readers (and poets) picture the ideal in their heads: Poetry should be majestic, unfathomably deep, universally powerful. Actual poems aren’t. But for Lerner, this divide between real poetry and ideal poetry is what this most elusive of arts is all about; poets are constantly pointing outside themselves to emotions and thoughts and experiences that are greater than they are. Dreams are always greater than reality, so the best poetry can do is point toward the dream.

Planetary Music

Lerner’s true strengths as a salesman appear when he discusses those who seized on poetry’s potential with their diverse imaginations.

John Keats, for instance, was the quintessential artiste, an interior designer of the mind, arranging and rearranging his words to create a shrine for a poetry that reached for the divine, but ultimately fell short: “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter.” Unfortunately, this disappointment comes with the territory; “I, too, can’t hear it,” shrugs Lerner in response to Philip Sidney’s lament that some people “cannot hear the planet-like music of poetry.”

Throughout his analyses, Lerner’s theory of poetry sounds essentially Romantic (and Keatsian) in its separation between real and ideal—but Lerner confesses to a flair for dramatic dissonance that led him to fond memories of Emily Dickinson. Dickinson challenged the poetics of potential head-on; she wanted to tear the roof off with verse that, written in eccentric shapes on envelopes and advertising flyers, blurred the boundaries of poetry. The central metaphor of the book is established in Dickinson’s “I Dwell In Possibility”:

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Though she could not transcend poetry to reach Poetry, Lerner’s almost-analysis of snippets of Dickinson show that if poetry is a room, she succeeded, at least, in putting in a skylight. For readers, the ceiling of poetic language suddenly seems taller. Rays of setting sun take on a suggestive cast.

From Personal to Universal

Lerner’s tone dips ominously as he calls up ghosts of the poetry-hating “avant-garde.” These revolutionaries who want to tear down the walls of poetry entirely with their reckless experiments with language. Despite their claims to be heroes whose work would change history and transcend time, these rabble-rousers were only poets whose works “might redefine the borders of art, but they don’t erase those borders; a bomb that never goes off, the poem remains a poem.”

Besides, with his “I contain multitudes,” Walt Whitman’s democratic rabble-rousing was more fun.

Lerner assures readers that they will fall for poetry’s frequent fumblings as he describes William Topaz McGonagall, possibly the clumsiest poet in history. In Lerner’s analysis of “The Tay Bridge Disaster,” he displays to great comedic effect just why McGonagall falls flat on his face. “And honestly,” Lerner says, “what better place to survey the grandeur of the place?” As readers laugh with—and at—McGonagall, even the skeptics must admit that they’re enjoying themselves immensely.

Lerner gets carried away in his rambling tour through poetic theory, but that’s part of his charm. Behind his self-effacing demeanor, Lerner’s subject is too dear for him to resist the odd foray into wordplay, just for the fun of it. He shows off in an irreverent defense of defenses of poetry, an approach that “allows you to make claims for and about Poetry while avoiding limitations of poems.”

And though it doesn’t make his own “hatred of poetry” overly convincing, it advances his claim that love of poetry must be personal before it can aspire to be universal.

Labor of Love

Lerner’s hatred of poetry may be more the “frustration” that comes with labors of love. But the poet’s humble bragging about his beloved art only recommends it more convincingly. By the time Lerner meanders amiably back through his suggestions about what could be done with the place, Lerner’s salesmanship—and his companionship—have done the trick.

Again, if poetry is a room for rent, Lerner makes it impossible not to stay awhile. Lerner’s words also linger, long after all practical reservations have gone to bed, urging that you open the window and listen for Sidney’s “planetary music of poetry.”

It’s not the room itself, but a place to host your dreams, that Lerner has sold you.