We’re far enough along in the Republican primary process — though not a single vote has been cast — that the field has winnowed down to a small number, and we can begin to project how each of them might win the nomination.

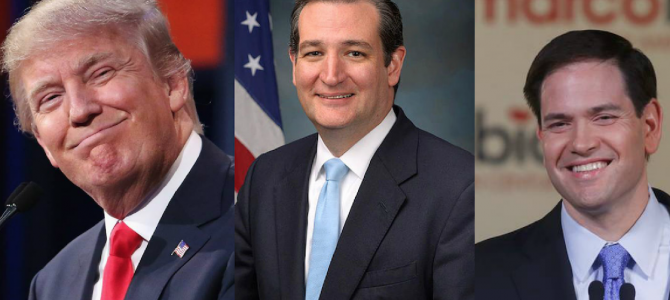

I see this is as three-man race right now: Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio.

Why? Because for everyone else, the path to the nomination begins with “and then a miracle occurs.” Well, maybe not a miracle. But they’re basically waiting for some spectacular and unexpected change of events that will break their way and suddenly everyone will discover, or rediscover, a candidate currently languishing at 5 percent or below in the polls. Maybe they’re hoping for something like the last Republican primary. In the 2012 cycle, it seemed like every candidate got his shot at being a front-runner. Just about everybody got to be the leading alternative to Mitt Romney for at least three weeks, even Rick Santorum, which might explain what he’s doing in the race this time around. (Yeah, he’s still officially running. I’ll understand if you didn’t notice.)

This is true even of poor Jeb Bush, who was supposed to be the “establishment” front-runner but just couldn’t get traction. Jeb’s only chance, and his actual strategy, is that somehow every other alternative to Trump will implode, leaving Jeb as the only sane choice. This, again, is hoping for a replay of 2012, because that’s basically how Mitt Romney won: by watching a series of challengers implode. But this time around, Jeb isn’t waiting for guys like Herman Cain to flame out. He needs two or three seasoned, successful, fairly well-tested national-level politicians to implode. And that’s really unlikely to happen.

So that leaves us with three candidates right now who have a plausible path to the nomination.

Donald Trump: This Time Is Different

The path to the nomination is not just about leading in the polls. It’s about winning primaries, winning delegates, and consolidating support.

Trump has the highest poll numbers, albeit in a very fragmented field, but it’s not as clear what his path is to the nomination. Specifically, it is currently looking like he won’t win the Iowa Caucus, where he is neck-and-neck with Cruz but has virtually no campaign organization, which is crucial in Iowa. He’s leading in New Hampshire and may win there, but he faces a tougher test in South Carolina.

His big advantage in the race all along has been the Trump Media Death Star — the use of his reality TV celebrity to suck away all the energy from everybody else’s campaign. His problem is that this is pretty much his entire campaign. Being on TV and getting attention for being on TV is what he’s good at, it’s what he’s been rewarded for over the decades, and he’s betting that the brute force of television celebrity will carry all before it.

But he doesn’t have the local campaign organization and “get out the vote” effort that a real campaign would have. And that matters a lot in the early primary states.

Some polls indicate that a lot of Trump supporters are independents or old-fashioned, disgruntled, blue-collar Democrats crossing over to the Republican Party to support him. But a lot of them are people who don’t normally vote, especially in the primaries. And when people don’t usually vote in the primaries, there’s an inertia you have to overcome. They may not know how the Iowa caucuses work, for example, or the date of the primary. So you need a really good “get out the vote” operation to mobilize them. You need lists of who your supporters are, a system for sending them reminders, and local organizers who can call them up and make sure they go to the polls.

Otherwise, you end up having what looks like really big support in the public opinion polls, but it melts away when the actual voting happens.

By the way, part of Trump’s problem is that he’s always citing polls where he’s doing really well. But he hasn’t splashed out the money for his own internal polling. What’s worse, he’s the kind of guy who touts every poll that shows him doing well while deriding as “junk” every poll that doesn’t show him doing well. The danger is that he’s only fooling himself. He has no basis for telling how he’s really doing or why.

And that lead us to another big factor. Regular political candidates have advisors who tell them how to adjust their message to attract the largest number of different constituencies and bring them together into a stable majority coalition. This is an additive process; it’s about “both-and.” You get both the evangelicals and the libertarians, by saying just enough to the first group to get them to like you without repelling the second, and vice versa.

Trump’s strategy, by contrast, has a major subtractive element. He has pandered so hard to one particular kind of voter that they have given him their fanatical devotion. My ultimate theory on Trump’s appeal is that his core base of support is the unpandered-to voter, the kind of people who feel they have been slighted and ignored by every other politician because no one has ever come out before and told them they’re absolutely right about how Mexican rapists pouring across the border are the source of all our problems, or about how we have to shut down trade with China because they’re taking away our jobs. I suspect that’s why these people are unfazed when you tell them that Trump doesn’t have a consistent record and that he’s just pandering to them and telling them what they want to hear. For these voters, that misses the real point. The point is that he’s pandering to them and telling them what they want to hear. Nobody’s ever really done that before, so they’re ecstatic.

But there’s a reason nobody ever panders to these voters, or at least why nobody ever panders to them as hard as Trump has. The harder you appeal to this one group, the more you risk alienating other groups. Pander to the hard-core anti-immigrationists and you lose the Hispanic vote. Pander to the wild-eyed populists and you lose the sober moderates. Pander to the emotion-driven voters, and you lose the ideological voters. You get huge support within a particular group at the expense of high opposition everywhere else. It’s a subtractive strategy.

This is an enormous problem in the general election, where Trump is spectacularly unpopular. As the New York Post observes, both parties are about to nominate candidates that most Americans hate. But it’s also a problem in the primaries. Trump is the only major Republican candidate where there are a lot of people in the party who would rather drive a rail spike through their foreheads than vote for him.

The fact that Trump has no campaign strategists is what makes people think “he’s genuine,” but they’re wrong. He’s not genuine. He’s pandering on immigration and trade, and the only fun thing about seeing him get the nomination would be watching him start the general election by selling out the people who got him there. So all they’re really seeing is a guy with no campaign strategists, who has no plan for how to win over and unite a majority.

Despite his lead in the polls, what makes me skeptical about Trump’s path to the nomination is that he only wins if This Time Is Different. He wins if celebrity culture has completely rewritten the rules and overturned everything everybody knows about running a campaign. And over the years, a lot of people have come to grief thinking that This Time Is Different.

A very smart analysis at RealClearPolitics describes how we can already see in Iowa the way Trump’s campaign might fall apart. As actual voting approaches and people start being influenced by something other than Trump-addicted national news — by local news, television ads, direct mail, and so on — Trump’s dominance fades. If all he’s got is the Trump Media Death Star, he’s vulnerable when it fails.

The real question with Trump isn’t whether he has a path to the nomination. It’s whether he has a path away from the nomination. What I mean is: If Trump does find himself with few wins and few delegates a few months from now, is there a way for him to declare victory and go home? The most plausible path away from the nomination would be for him to announce that he has changed the party’s agenda and brought his issues to the forefront, so his work here is done. And to do that, he would have to point to the one candidate whose positions are most similar to his, Ted Cruz.

But that raises a whole other problem, and it leads us to the question of Ted Cruz’s path to the nomination.

Ted Cruz: Trump-Lite Without Trump

The reason why Trump won’t be able to point to Cruz as evidence that his work here is done is because he has been busy attacking Cruz and undermining him in a way that will be deeply influential with Trump’s supporters. And that’s a big problem for Cruz’s path to the nomination.

Cruz’s strategy up to now has been to sidle up to Trump, to echo some of his rhetoric and to seek an unofficial detente or even a “bromance” between the two candidates, in order to avoid having the Trump Media Death Star focus its destructive energy on him. In the meantime, Cruz would out-organize Trump in Iowa and South Carolina, take those victories out from under him, offer Trump a graceful exit — and scoop up his supporters.

Part of Cruz’s calculation has to be that, unlike Trump, he can still pursue a traditional additive approach. While Trump creates a rift between the emotional-populist wing of the base and the ideological Republicans, Cruz is betting that he can appeal to the first group now, then turn around and appeal to the second group later. He’s an articulate, Harvard-educated debate champion who first made a name for himself by memorizing the Constitution. So the ideological conservatives know he is one of their own, and he’s hoping they will forgive him for playing around with Trump-lite populism. And let’s face it, we will, if it’s a choice between him and Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders.

The problem is that Trump isn’t playing along with this strategy. As Cruz has risen in the polls, Trump has begun to attack him — and he is deploying attacks that stick. They may not stick with the general public or even with most Republicans. But they’re exactly the kind of attacks that are going to stick with Trump’s supporters, the ones Cruz is counting on.

The danger for Trump and Cruz is mutually assured destruction. Unflappable and with a talent for dry, acerbic humor, Cruz may be the only candidate who can turn the weapon of ridicule back on Trump and make it work. We saw a bit of that in the last debate.

But Trump can poison his supporters against Cruz, particularly by reviving the “birther” attack which claims that Cruz, having been born in Canada to an American mother, is not constitutionally eligible to run for president. This claim might be refuted by multiple legal experts, but when did Trump’s supporters ever listen to experts?

Cruz still has the most likely path to the nomination, the best chance of posting strong results in early contests like Iowa and South Carolina, then building momentum and getting voters to rally around him.

But by going more populist in a bid to gain Trump supporters, Cruz has opened room in the race, not only for a more moderate candidate, but also for a more ideologically consistent candidate. And Cruz wasn’t supposed to be vulnerable to that kind of challenge. We can see that danger in the release of a new National Review symposium in which a wide range of ideological conservatives stand athwart history yelling, “Stop Trump!” This is Cruz’s opportunity to distance himself from Trump, but it presents him with a dilemma: risk losing his shot at Trump’s supporters, or risk alienating the ideological conservatives. And who are the alienated conservatives going to turn to?

That leads us to the last candidate who I think still has a path to the nomination.

Marco Rubio: The “Establishment” Underdog

What makes this year’s primaries so hard to figure out is that we entered the race with no “establishment” candidate whose turn it was for the nomination. (Donors who were talked into the idea that Jeb Bush was inevitable got fleeced to the tune of about $100 million.) This shifted the momentum to the most loud-mouthed and exciting candidates, particularly the ones who billed themselves as “outsiders,” and that meant the more traditional candidates — the kind who cultivated an image of being sober, thoughtful, and “presidential” — ended up splitting the vote among them and getting lost in the shuffle. This would have been the case in any election cycle, but the Trump Media Death Star made it all the more difficult for these candidates to get any of the voters’ attention. (So long, Rick Perry and Bobby Jindal.) So we end up with a strange year in which the more “establishment” candidates are the struggling underdogs.

I’m no great fan of “the establishment,” but this is not as desirable an outcome as you might think. The reason is that, six months from now, we’re going to be sending a Republican nominee into the general election, and that’s precisely when being sober, thoughtful, and presidential are big virtues. Cruz might be able to make that transition, though he has spent his entire national political career building an image as a radical firebrand who doesn’t work and play well with others. Trump is constitutionally incapable of it.

This is what I mean about an additive strategy. It doesn’t end with the primaries. Ideally, the person who wins the primaries is the person who is able to add together the ideologues, the populists, the libertarians, the hawks, the religious voters, and so on. He must then continue to add on the independents, the moderates, the conservative Democrats, and so on.

On paper, the person most capable of doing this is Rubio. He had just enough Tea Party credentials — having defeated a big-government Republican — to appeal to the radicals, but his earnest demeanor and interest in forging political compromises would make him acceptable to the moderates and establishment. As for the ideological wing of the right, here I must confess my own preference. I have found Rubio very appealing because when it comes to the big intellectual and policy issues, he is able to talk substantively and eloquently, in a way that indicates he understands the issues first-hand and in detail. If you’re from the ideological wing of the right, you’re used to having politicians throw out a bunch of well-worn slogans to indicate their loyalty to your cause — but what you really want is someone who is capable of going beyond slogans and understanding the issues. Rubio consistently does that. I don’t always agree with exactly where he stands, but his ability to deal with politics on a thoughtful, intellectual level makes me think he is reachable by rational argument, which is what we ideologues look for above all.

This is the advantage that Rubio has over Cruz right now. I know that Cruz understands all of the ideological issues perfectly well. But the comfort with which he has courted Trump and his non-ideological populists makes me wonder about the sincerity of his commitment—whether he will sacrifice his ideological loyalties to his personal ambition. Of course, I wonder the same thing about any politician, and I assume that ultimately the answer will be “yes.” But I have been reassured by Rubio’s refusal to pander to wild-eyed Trumpism.

Yet this year hasn’t worked out as planned. With Trump out-bidding for the emotional-populist wing of the right by offering them everything they ever wanted, he has taken those voters away from every other candidate, and they may never come back. But Rubio still has a path to the nomination by becoming the leading non-Trump.

And if he wins, Rubio has the clearest path to winning in the general election, because he is by far the best equipped to continue an additive strategy, appealing to independents, moderates, and conservative Democrats, and by generally appearing idealistic, thoughtful, and sincere. Judging from the lame attempts so far at personal attacks on him, he will be impossible for the mainstream media to demonize. (By contrast, the combative radicalism that makes Cruz appealing also makes it very easy to demonize him, and Trump — who is famous for hosting a show in which he fires people on live TV — is already demonized.)

But how does Rubio get there? It’s easy to see how he does well in the general election, but he has to get through the primaries first.

It’s actually not so difficult to see his route. He doesn’t have to win the early primaries. All he has to do is to emerge as the third man after Trump and Cruz. It’s like the old adage about how you don’t have to outrun the lion, you just have to outrun the guy next to you. All Rubio has to do is to outrun his closest competitors: Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and Ben Carson. At that point, it is likely that these other candidates will drop out, and Rubio will pick up their voters. A constituency that is now scattered among three to six candidates will coalesce around him.

Here is the calculation. If you add to Rubio’s RCP poll average the share currently going to the candidates who are most similar to him (Bush, Christie, and Carly Fiorina), he would be at a little over 22 percent in the polls, about four points higher than Cruz. I’m assuming he won’t get many of Rand Paul’s libertarians, and God only knows what John Kasich’s people will do. But it’s reasonable to speculate that Rubio would catch a significant percentage of the votes now going to the mild-mannered Carson, plus some undecideds and voters now supporting other minor candidates. That would put him between 25 percent and 30 percent, right up there between the two leading candidates.

It is easy to lose sight of this possibility and to dismiss Rubio because he hasn’t been able to break out against the Trump Media Death Star. But this might be falling into a basic media bias. Even John Podhoretz, whom we can certainly count as a leader of the ideological wing of the right, praised Rubio’s performance in the last Republican debate as showing that he was a contender — but only because of the “fireworks” of Rubio’s attack on Cruz over inconsistencies in his record. Yet this assumes “theatrics” are the only way to get the voters’ attention. What if that isn’t true?

The problem with professional political commentators is that they are easily distracted by the things that make for “fireworks” when you’re trying to write or report on a subject — people fighting, making gaffes, saying outrageous things. A candidate simply stating his platform and message to voters seems unbelievably boring, because we have already heard it a hundred times on the campaign trail. Nothing new to us, nothing exciting, so therefore: nothing. From this perspective, Trump looks like he’s at the center of everything that’s happening. But it’s likely that our perspective differs from that of the average voter.

My own suspicion is that the “fireworks” tend to dominate before actual primary voting begins, because voters are paying so little attention that these are the only stories they see. But as voters begin to pay more attention, they are more reachable by the actual substance of a candidate’s ideas and character. It’s a factor that will work against Trump and in favor of Rubio.

You may reply that this means Rubio is relying on a miracle. On the other hand, it would be very unusual if several wings of the Republican Party — the more ideological, the establishment, and the moderates — were to have nobody to represent them in the final matchup. If you posit a two-man race between Cruz and Trump, you’re assuming that at least one quarter of the party is just going to be sitting this out. I think it’s much more likely that they will find a candidate to rally around, and Rubio is by far in the best position to be that candidate.

I could be wrong, but I see three leading candidates with three paths to the nomination. Each has elements that are plausible and elements that are implausible, and we’ll get our first solid evidence about which ones are actually realistic in a little more than a week.

Follow Robert on Twitter.