“Deal from strength or get crushed every time” sang the Freedom Girls at a January 14 Donald Trump rally. Seeing young girls perform this may seem jarring, but it should not surprise: Trump’s campaign is all about strength.

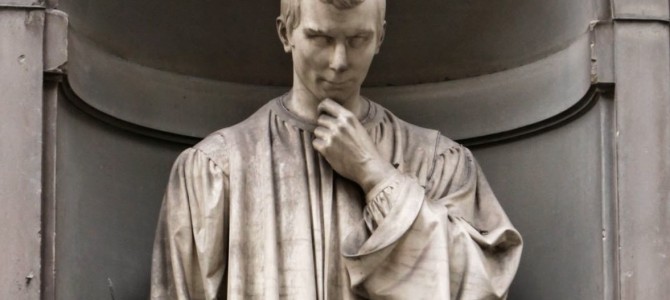

Strength does matter in leaders, as Niccolo Machiavelli recognized in “The Prince,” his sixteenth-century leadership guide. According to presidential historian Tevi Troy, Trump has read “The Prince.” Trump’s campaign so far has proven him Machiavelli’s student, albeit an imperfect one, as his statements concerning strength, military knowledge, advisers, and potential governing techniques reveal.

1. How You Use Strength Matters

Strength is key in understanding Trump. This month, he expressed admiration for North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, whose assumption of power in North Korea despite his relative youth impressed Trump. Last December, when Trump received a quasi-endorsement from Russian President Vladimir Putin, he quasi-accepted it, calling Putin a “strong leader.” And in a 1990 Playboy interview, Trump condemned the Chinese government’s response to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, not for excessive harshness but for an initial lack thereof.

In all this, Trump apes Machiavelli, who not only stressed that “it is much safer to be feared than to be loved” but also that apparent “cruelties” become sensible if undertaken swiftly to achieve desired goals. Machiavelli preferred strong initial action to accomplish desired ends to prolonged suffering from hesitation. Trump respects Kim Jong Un and Putin for their finesse in securing power, while faulting the Chinese government for insufficient initial strength in suppressing unrest.

This fits the amoral, ends-justify-means Machiavelli of popular stereotype. But Machiavelli is more than that. In addition to providing advice useful regardless of moral intent, he also stressed that leaders consider “the people,” i.e., the majority. The people have simple desires: “not to be oppressed,” and that their leader “abstains from the goods of his citizens and subjects…”

Kim Jong Un, the Chinese government, and Putin become less defensible in this light. The first two may have accomplished their goals, but not in service of their people, whom they oppress. Putin, while admittedly popular in Russia, is lethally hostile to criticism. Trump must remember that Machiavelli taught not that all displays of strength are equal, but that strength is best in service of a proper end, not as an end in itself.

2. Military Knowledge Is Key

Trump’s limited military knowledge is also worrisome. Although he has an admirably simple plan (according to a campaign ad: “Cut off the head of ISIS and take their oil”), he lacks specifics. Last August, when asked where he gets military advice, he said “the shows.” He also demonstrated a worrying ignorance of the nuclear triad, the threefold capacity of U.S. nuclear armaments, at the December 15 Republican debate, despite being tripped up by the same question previously.

A true Machiavellian would leave no doubt of his military prowess. For Machiavelli, “[a] prince…ought to have no other object nor any other thought, nor take anything else for his art, but war…” Without this knowledge, a leader can guarantee neither his own position nor his regime’s security, for “a prince who does not himself understand military things cannot be esteemed by his soldiers, nor can he have trust in them.” Trump’s lack of a strategic vision suggests he has not yet followed this advice of Machiavelli.

3. You Can’t Rely on Advisers

Nor could a President Trump rely on advisers. That he nonetheless insists he could makes this the area in which Trump most ignores Machiavelli. A standard Trump response to questions exposing his lack of specifics or knowledge about a topic is he will “find the right people” to advise him.

As Trump responded to skeptical questioning from Hugh Hewitt in the September 28 CNN Republican debate: “I will have the finest team that anybody has put together and we will solve a lot of problems.” But if a President Trump relied excessively on advisers, they would likely know more than he and dominate his policy. Yet if he relied on people less knowledgeable than he, they would only flatter and affirm whatever he does, even if wrong.

Anything other than Machiavelli’s approach of knowing enough initially about the pertinent issue, enlisting wise counselors, inquiring them only about the issue at hand, and making the ultimate decision oneself risks falling into the trap Machiavelli described of being “either overthrown by flatterers, or…so often changed by varying opinions that he falls into contempt.”

4. Upsetting the Status Quo Is Harder Than Trump Thinks

Finally, Trump’s strategy if voted president reveals further inattentiveness to Machiavelli. Implicit in much of Trump’s criticism of politics today—such as of the Iran deal, job losses, and the Republican budget deal—is that our leaders are bad negotiators. Meanwhile, he is the supreme negotiator, who by sheer volition could impose his will.

Trump’s outsized confidence in himself, however, seems to have made him forget, as Machiavelli wrote, that “nothing is more difficult to deal with nor more dubious of success nor more dangerous to manage than making oneself the head of new orders,” because the status quo’s beneficiaries care more about its preservation than most of its opponents care about its upset.

Our status quo would likely treat a President Trump as a hostile invader. To defeat the massive, increasingly independent bureaucracy controlling our government, Trump would have to conquer it. Unfortunately, in Machiavelli’s terms, Trump seems to think of our government as a foreign state with one ruler (a president), whose “defeat,” while difficult, guarantees control, while it in fact more resembles one with many smaller but still powerful rulers (bureaucrats) who will allow initial control but resist total conquest with collective stubbornness. This is not even to mention Congress, many of whose members already oppose Trump. Sheer volition would not suffice.

Donald Trump, then, is an imperfect student of Niccolo Machiavelli. But he’s at least trying, and could improve. Or he could continue to bluster and berate his way to the Republican nomination and the presidency. It’s his choice to make.