Many statists are worried that Republicans may install new leadership at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This is a big issue because these two score-keeping bureaucracies on Capitol Hill tilt to the left and have a lot of power over fiscal policy.

The JCT produces revenue estimates for tax bills, yet all their numbers are based on the naive assumption that tax policy generally has no impact on overall economic performance.  Meanwhile, CBO produces both estimates for spending bills and also fiscal commentary and analysis, much of itbased on the Keynesian assumption that government spending boosts economic growth.

Meanwhile, CBO produces both estimates for spending bills and also fiscal commentary and analysis, much of itbased on the Keynesian assumption that government spending boosts economic growth.

I personally have doubts whether GOPers are smart enough to make wise personnel choices, but I hope I’m wrong.

Matt Yglesias of Vox also seems pessimistic, but for the opposite reason.

He has a column criticizing Republicans for wanting to push their policies by using “magic math” and he specifically seeks to debunk the notion – sometimes referred to as dynamic scoring or the Laffer Curve – that changes in tax policy may lead to changes in economic performance that affect economic performance.

He asks nine questions and then provides his version of the right answers. Let’s analyze those answers and see which of his points have merit and which ones fall flat.

But even before we get to his first question, I can’t resist pointing out that he calls dynamic scoring “an accounting gimmick from the 1970s” in his introduction. That is somewhat odd since the JCT and CBO were both completely controlled by Democrats at the time and there was zero effort to do anything other than static scoring.

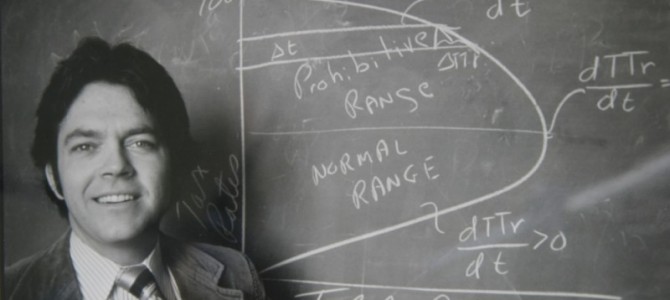

I suppose Yglesias actually means that dynamic scoring first became an issue in the 1970s as Ronald Reagan (along with Jack Kemp and a few other lawmakers) began to argue that lower marginal tax rates would generate some revenue feedback because of improved incentives to work, save, and invest.

Now let’s look at his nine questions and see if we can debunk his debunking.

1. The first question is “What is dynamic scoring?” and Yglesias responds to himself by stating it “is the idea that when estimating the budgetary impact of changes in tax policy, you ought to take into account changes to the economy induced by the policy change” and he further states that it “sounds like a reasonable idea.”

But then he says the real problem is that conservatives exaggerate and “say that large tax cuts will have a relatively small impact on the deficit — or even that they make the deficit smaller” and that they “cite an idea known as the Laffer Curve to argue that tax cuts increase growth so much that tax revenues actually rise.”

He’s sort of right. There are definitely examples of conservatives overstating the pro-growth impact of tax cuts, particularly when dealing with proposals – such as expanded child tax credits – that presumably will have no impact on economic performance since there is no change in marginal tax rates on productive behavior.

But notice that he doesn’t address the bigger issue, which is whether the current approach (static scoring) is accurate and appropriate even when dealing with major changes in marginal tax rates on work, saving, and investment. That’s what so-called supply-side economists care about, yet Yglesias instead prefers to knock down a straw man.

2. The second question is “What is the Laffer Curve?” and Yglesias answer his own question by asserting that the “basic idea of the curve is that sometimes lower tax rates lead to more tax revenue by boosting economic growth.” He then goes on to ridicule the notion that tax cuts are self-financing, even citing a column by National Review’s Kevin Williamson.

Once again, Yglesias is sort of right. Some Republicans have made silly claims, but he mischaracterizes what Williamson wrote.

More specifically, he’s wrong in asserting that the Laffer Curve is all about whether tax cuts produce more revenue. Instead, the notion of the curve is simply that you can’t calculate the revenue impact of changes in tax rates without also measuring the likely change in taxable income. The actual revenue impact of changes in tax rates will then depend on whether you’re on the upward-sloping part of the curve or downward-sloping part of the curve.

More specifically, he’s wrong in asserting that the Laffer Curve is all about whether tax cuts produce more revenue. Instead, the notion of the curve is simply that you can’t calculate the revenue impact of changes in tax rates without also measuring the likely change in taxable income. The actual revenue impact of changes in tax rates will then depend on whether you’re on the upward-sloping part of the curve or downward-sloping part of the curve.

The real debate is the shape of the curve, not whether a Laffer Curve exists. Indeed, I’m not aware of a single economist, no matter how far to the left (including John Maynard Keynes), who thinks a 100 percent tax rate maximizes revenue. Yet that’s the answer from the JCT. Moreover, the Laffer Curve also shows that tax increases can impose very high economic costs even if they do raise revenue, so the value of using such analysis is not driven by whether revenues go up or down.

3. The third question is “So do tax cuts boost economic growth?” and Yglesias responds by stating “the credible research on the matter is very very mixed.” But he follows that response by citing research which concluded that “a tax cut financed by reductions in wasteful spending or social assistance for the elderly would boost growth.”

But that leaves open the question as to whether the economy does better because of the lower tax burden, the lower spending burden, or some combination of the two effects. But I’ll take any of those three answers.

So is he “sort of right” again? Not so fast. Yglesias also cites the Congressional Research Service (which rubs me the wrong way) and a couple of academic economists who concluded that there is “no systematic correlation between the level of taxation and the level of economic growth.”

The bottom line is that there’s no consensus on the economic impact of taxation (in part because it is difficult to disentangle the impact of taxes from the impact on spending, and that’s not even including all the other policies that determine economic performance). But I still think Yglesias is being a bit misleading because there is far more consensus on the economic impact of marginal tax rates and debates about the Laffer Curve and dynamic scoringvery often revolve around those types of tax policies.

4. The fourth question is “How does tax scoring work now?” and Yglesias respond to himself by noting that the various score-keeping bureaucracies measure “demand-side effects” and “behavioral effects.”

He’s right, but CBO uses so-called demand-side effects to justify Keynesian spending, so that’s not exactly reassuring news for people who focus more onreal-world evidence.

And he’s also right that JCT measures changes in behavior (such as smokers buying fewer cigarettes if the tax goes up), and this type of analysis (sometimes called microeconomic dynamic scoring) certainly is a good thing.

But the real controversy is about macroeconomic dynamic scoring, which we’ll address below.

5. The fifth question is “Can we take a break from all this macroeconomic modeling?” and is simply an excuse for Yglesias to make a joke, though I can’t tell whether he is accusing Reagan supporters of being racists or mocking some leftists for accusing Reagan supporters of being racist.

So I’m not sure how to react, other than to recommend the fourth video at this link if you want some real Reagan humor.

6. The sixth question is “What do current scoring methods leave out?” and Yglesias accurately notes that what “dynamic-scoring proponents want is a model of macroeconomic consequences. They think that a country with lower tax rates will see more investment in physical and human capital, leading to more productivity, and more economic growth.”

He even cites my blog post from last month and correctly describes me as believing that it is “self-evidently ridiculous that the current CBO model says higher tax rates would lead to faster economic growth via lower deficits.”

I also think he is fair in pointing out that “people sharply disagree about how much tax rates actually influence economic growth” and that “the whole terrain is enormously contested.”

But this is why I think my view is the reasonable middle ground. At one extreme you find (at least in theory) some over-enthusiastic Republican types who argue that all tax cuts are self-financing. At the other extreme you find the JCT saying tax policy has no impact on the economy and actually arguing that you maximize tax revenue with 100 percent tax rates. I suspect that Yglesias, if pressed, will agree the JCT approach is nonsensical.

So why not have the JCT – in a fully transparent manner – begin to incorporate macroeconomic analysis?

7. The seventh question is “Has dynamic scoring ever been tried?” and Yglesias self-responds by pointing out that a Treasury Department dynamic analysis of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts come to the conclusion that “the resulting budget impact would be 7 percent smaller than what was suggested by conventional scoring methods.” and “ended with the conclusion that the Bush tax cuts substantially decreased revenue.”

In other words, dynamic analysis was not used to imply that tax cuts are self-financing. Indeed, the dynamic score in the example of what would happen if the Bush tax cuts were made permanent turned out to be very modest.

So why, then, are folks on the left so determined to block reforms that – in practice – don’t yield dramatic changes in numbers? My own guess, for what it’s worth, is that they don’t want any admission or acknowledgement that lower tax rates are better for growth than higher tax rates.

8. The eight question is “Why are we talking about dynamic scoring now?” and Yglesias answers his own question by accurately stating that “the Republican takeover of Congress starting in 2015 gives the GOP an opportunity to either change the scoring rules, change the personnel in charge of the scoring, or both.”

He’s not just sort of right. He’s completely right. I have no disagreements.

9. The ninth question is “Why does the score matter?” and his self-response is “the scores matter because perceptions matter in politics.” In other words, politicians don’t want to be accused of enacting legislation that is predicted to increase red ink.

Yglesias is also right when he writes that this “effect shouldn’t be exaggerated. In the past, Republicans haven’t hesitated to vote for tax measures that the CBO says will increase the deficit. That’s because they have a strong preference for low tax rates.”

At the risk of being boring, I also think he’s right about the degree to which scores matter.

The bottom line is that questions #1, #2, #3, and #6 are the ones that matter. Yglesias makes plenty of reasonable points, but I think his argument ultimately falls flat because he spends too much time attacking the all-tax-cuts-pay-for-themselves straw man and not enough time addressing whether it is reasonable for the JCT to use a methodology that assumes taxes have no effect on the overall economy.

But I expect to hear similar arguments, expressed in a more strident fashion, if Republicans take prudent steps – starting with personnel changes – to modernize the JCT and CBO apparatus.

P.S. While tax cuts usually do lead to revenue losses, there is at least one very prominent case of lower tax rates leading to more revenue.

P.P.S. If the JCT approach is reasonable, why do theoverwhelming majority of CPAs disagree? Is it possible that they have more real-world understanding of how taxpayers (particularly upper-income taxpayers) respond when tax rates change?

P.P.S. If the JCT approach is reasonable, why do theoverwhelming majority of CPAs disagree? Is it possible that they have more real-world understanding of how taxpayers (particularly upper-income taxpayers) respond when tax rates change?

P.P.P.S. If the JCT approach is reasonable, why do international bureaucracies so often produce analysis showing a Laffer Curve?

- Such as this study from the OECD acknowledging that lower tax rates can lead to more taxable income.

- Or this study by the IMF, which not only acknowledges the Laffer Curve, but even suggests that the turbo-charged version exists.

- Or this European Central Bank study showing substantial Laffer-Curve effects.

- Or the United Nations admitting that the Laffer Curve limits the feasible amount of taxes that can be imposed.

There’s also some nice evidence from Denmark, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom.

This article is reprinted from the author’s blog.