One of the ongoing debates about policy formation in Washington which has become far more prominent since the passage of Obamacare is the role of the Congressional Budget Office, and the weight given its estimates and predictions for the ramifications of legislation. CBO has always been at the center of a debate about how much we should trust these estimates and how much legislators should rely on them in crafting policy. The larger the legislation, the more moving parts it has, the more difficult it is to calculate the fiscal and economy-wide impacts.

In the case of Obamacare, the sheer largeness of the measure and its many factors contributed to a higher degree of distrust for the CBO’s assumptions about what would come of Obamacare’s passage. In certain key areas, such as the impact of the long-term care provision known as the CLASS Act, the CBO’s position was laughable – and scores of other steps since then have also attracted pushback. The level of distrust for the validity of CBO’s estimates is growing, and their latest step to game the accounting on Obamacare’s ramifications, which has attracted little notice thus far but represents another step to make the law harder to repeal, is likely to only increase calls for changes and reforms of the office.

In its final cost estimate of Obamacare (released on March 20, 2010), under a section labeled “Key Considerations,” the CBO cautioned that the legislation would “maintain and put into effect a number of policies that might be difficult to sustain over a long period of time.” Thus, CBO asserted: “the long-term budgetary impact could be quite different if key provisions… were ultimately changed or not fully implemented” (emphasis added). Specifically, CBO mentioned the sustainable growth rate formula for paying doctors in Medicare that was not addressed in the bill, but—more importantly—here’s what CBO said about Medicare payment rates for other health care providers:

“….the legislation includes a number of provisions that would constrain payment rates for other providers of Medicare services. In particular, increases in payment rates for many providers would be held below the rate of inflation (in expectation of ongoing productivity improvements in the delivery of health care). The projected longer-term savings for the legislation also reflect an assumption that the Independent Payment Advisory Board…would be fairly effective in reducing costs beyond the reductions that would be achieved by other aspects of the legislation.”

“Under the legislation, CBO expects that Medicare spending would increase significantly more slowly during the next two decades than it has increased during the past two decades (per beneficiary, after adjusting for inflation). It is unclear whether such a reduction in the growth rate of spending could be achieved, and if so, whether it would be accomplished through greater efficiencies in the delivery of health care or through reductions in access to care or the quality of care. The long-term budgetary impact could be quite different if key provisions of the legislation were ultimately changed or not fully implemented.”

Just the day before, CBO had released a sensitivity analysis (at Paul Ryan’s request) that illustrated a similar point. Ryan asked what the budget impact of Obamacare would be in its second decade if several provisions were altered. Two of the four provisions he inquired about were IPAB and the additional indexing for exchange subsidies. In that analysis, CBO found that (emphasis added):

“If the changes described above were made to the legislation, CBO would expect that federal budget deficits during the decade beyond 2019 would increase relative to those projected under current law—with a total effect during that decade in a broad range around one-quarter percent of GDP.”

After Obamacare passed, starting with its first long term budget outlook report (released in June 2010), CBO included an important section titled “Questions about Sustainability.” In it CBO again stated that “the recent legislation either left in place or put into effect a number of procedures that may be difficult to sustain over a long period.” See page 37 here, where CBO openly questioned whether the Medicare cuts in Obamacare and the cap on the new exchange subsidies, in particular, could be sustained over time.

“…the legislation includes provisions that will constrain payment rates for other providers of Medicare’s services. In particular, increases in payment rates for many providers will be held below the rate of increase in the average cost of providers’ inputs.”

“Another provision that may be difficult to sustain will slow the growth of federal subsidies for health insurance purchased through the insurance exchanges. For enrollees who receive subsidies, the amount they will have to pay depends primarily on a formula that determines what share of their income they have to contribute to enroll in a relatively low-cost plan (with the subsidy covering the difference between that contribution and the total premium for that plan). Initially, the percentages of income that enrollees must pay are indexed so that the subsidies will cover roughly the same share of the total premium over time. After 2018, however, an additional indexing factor will probably apply; if so, the shares of income that enrollees have to pay will increase more rapidly, and the shares of the premium that the subsidies cover will decline.”

As most observers of the budget process know, CBO produces long-term budget projections under two scenarios: there’s the extended-baseline scenario (current law) and one or more alternative fiscal scenarios (often viewed as a more realistic fiscal trajectory, since they take other factors into account). As a result of questions about their sustainability, CBO assumed that these policies were not effective after the 10-year budget window for purposes of their alternative scenario projections. The 2010 long term outlook report notes:

“Under the extended-baseline scenario, projected federal spending is assumed to be constrained by a number of policies specified in the recent health care legislation—the continuing reductions in updates for Medicare’s payment rates, the constraints on Medicare imposed by the IPAB, and the additional indexing provision that will slow the growth of exchange subsidies after 2018. Because those policies may be difficult to maintain over the long term, in the alternative fiscal scenario it is assumed that they will not continue after 2020.”

Here’s where it gets interesting: every CBO long-term outlook report since Obamacare was enacted included these same assumptions in the alternative scenario—until this year.

Here’s a link to all of CBO’s long term outlook reports. The 2014 long-term outlook included a little-noticed section labeled “Changes in Assumptions Incorporated in the Extended Alternative Fiscal Scenario” on page 117-8 of Appendix B of its report. It reads (emphasis added):

“Under its extended alternative fiscal scenario last year, CBO assumed that lawmakers would not allow various restraints on the growth of Medicare costs and health insurance subsidies to exert their full effect after the first 10 years of the projection period. However, this year, after reassessing the uncertainties involved, CBO no longer projects whether or when those restraints might wane. Instead, for those elements of the alternative fiscal scenario, there are now no differences from the extended baseline. For both, CBO projects that growth rates for Medicare costs will move linearly over 15 years (from 2024 to 2039) to the underlying rate that the agency has projected and that the exchange subsidies will do the same. (One exception to that new approach, though, concerns Medicare’s payment rates for physicians’ services. This year, as in previous years, projected spending under the alternative fiscal scenario reflects the assumption that those payment rates would be held constant at current levels rather than being cut by about a quarter at the beginning of 2015, as scheduled under current law.)”

Beyond that brief mention of the change in its assumptions, there is no other discussion of the rationale behind the exchange subsidy provision. How significant was this unnoticed change in CBO’s assumptions? According to a health care aide on Capitol Hill who has closely followed the scorekeeping of the law, analysis of the CBO data suggests that over the 75-year period, this change in assumptions lowers projected spending by about $6.2 trillion.

This is a pretty big change, to say the least, particularly one for which the CBO hasn’t given any justification at all. Their latest update on health care spending doesn’t even mention it. The only other discussion of the Medicare provider cuts in Obamacare appears on pages 37-8 of the report, where it notes that:

“An important source of uncertainty in projecting health care spending in the long term under current law is how providers would respond to the scheduled restraint in annual updates to Medicare’s payment rates—and whether those responses would lead to offsetting increases or further reductions in spending for Medicare and other health care programs. The scheduled updates in the payment rates for providers other than physicians would generally fall below increases in the prices of inputs (namely, labor and supplies) used to deliver care. The difference between the changes in payment rates and in input prices reflects an adjustment for economywide increases in productivity. For example, CBO projects that Medicare’s payment rates for most hospitals will grow by 2.2 percent per year over the 2019–2024 period but that prices for hospitals’ inputs will grow by 3.3 percent per year. Overall price inflation as measured by the rate of increase in the GDP price index is projected to be 2.0 percent over that same period…

“Over the long term, how Medicare providers other than physicians will respond to the payment updates specified in current law is unclear; in particular, it is unclear whether their responses will generate offsetting increases in spending or will further reduce spending. Reflecting that uncertainty, CBO has not adjusted its projections of spending in the long term to take such possible responses into account.”

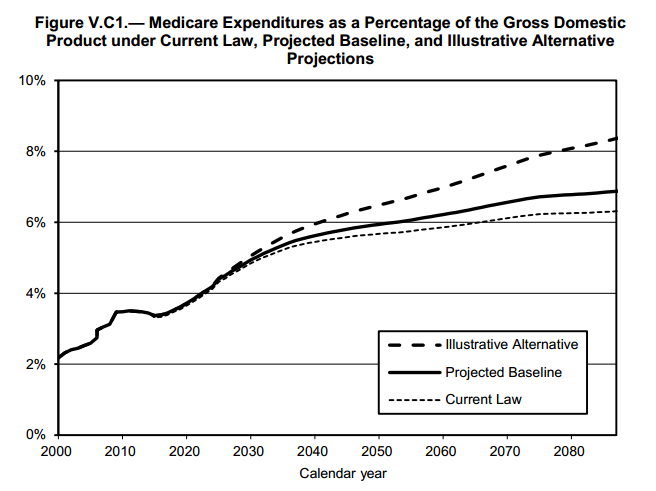

So the question is: are they outside the mainstream on their new assumptions? Well, in every Medicare Trustees’ reports since the President’s health care law was enacted, the administration’s own non-partisan Chief Actuary of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) used his statement of actuarial opinion at end of the report to warn that these cuts aren’t sustainable:

“…the financial projections shown in this report for Medicare do not represent a reasonable expectation for actual program operations in either the short range (as a result of the unsustainable reductions in physician payment rates) or in the long range (because of the strong likelihood that the statutory reductions in price updates for most categories of Medicare provider services will not be viable).”

The Chief Actuary encourages readers to view his “illustrative alternative” based on “more sustainable assumptions” than the Trustees’ official current law estimates. The actuary’s alternative scenario assumes the Medicare provider cuts are phased out after the 10-year window:

“it assumes that the productivity adjustments would be applied fully through 2019 but then phased out over the 15 years beginning in 2020. In 2034 and later, Medicare Part A and Part B per capita cost growth rates are assumed to equal the pre-ACA “baseline” growth rates, as determined by the CGE growth model.”

The most recent Trustees’ report notes that “the actual future costs for Medicare may exceed those shown by the projected baseline projections in this report, possibly by substantial amounts.” Therefore, “To help illustrate and quantify the potential magnitude of the cost understatement, the Trustees have asked the Office of the Actuary to prepare an illustrative Medicare trust fund projection under a hypothetical alternative that assumes that, starting in 2020, the economy-wide productivity adjustments gradually phase down to 0.4 percent.” Here’s what that looks like:

So here’s where we are now: the Congressional Budget Office is making sweeping assumptions about the future costs of Obamacare and Medicare, assumptions which are at odds with the projections of the administration’s own Chief Actuary at Medicare and which have no explained basis. The CBO doesn’t show its work, but you should probably just trust them: what’s a difference of about six trillion dollars between friends?