Ross Douthat has written on the revival of Marxism as a seductive theory in the wake of burgeoning economic inequality and the withering away of the middle class. He might have said that the futurist most attuned to both those trends is the savvy libertarian economist Tyler Cowen in his Average Is Over.

Cowen says, in effect, that capitalism has won in the form of genius machines and those who are skilled and smart enough to work comfortably with them. That cognitive elite that will be—and deserve to be—richer than rich will make up maybe twenty percent of the population. The rest of us will sink into a kind of marginal productivity and something like an idiocracy. Our less-than-average producers will be diverted from their misery by all the enjoyments—such as games and Internet porn—available to them on screens.

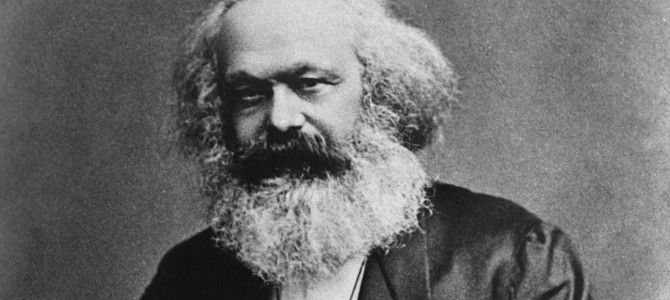

Surely Cowen exaggerates! Well, if he does, it is in the way a Marxist would in describing the outcome of the development of the division of labor in our time. What Marx failed to predict, of course, is the screen.

Cowen, as an unabashed and unbounded fan of both technology and individual liberty, has no problem putting a positive spin on the facts that Marx thought would produce the hateful misery that is the prelude to inevitable revolution. Marx, we shouldn’t forget, was himself quite the enthusiast when describing capitalism’s wonderful conquest of scarcity and global urbanization—the latter, of course, saving so many from rural idiocy.

The libertarian economist and Marx (also quite an economist) agree that what Cowen calls “the light at the end of the tunnel” is the prospect of a time to come when we can all unobsessively revel in whatever hobby pleases us the most at the moment. Their utopian fantasies are pretty darn similar. Neither Cowen nor Marx think of “the realm of freedom” as an idiocracy, but in some ways were stuck with wondering why.

Douthat finishes up by reminding us that the genuinely negative view of the observation that “capitalism has won” can be found these days among non-libertarian conservatives:

The taproot of agitation in 21st-century politics, this trend suggests, may indeed be a Marxian sense of everything solid melting into air. But what’s felt to be evaporating could turn out to be cultural identity — family and faith, sovereignty and community — much more than economic security.

And somewhere in this pattern, perhaps, lies the beginnings of a more ideologically complicated critique of modern capitalism — one that draws on cultural critics like Daniel Bell and Christopher Lasch rather than just looking to material concerns, and considers the possibility that our system’s greatest problem might not be the fact that it lets the rich claim more money than everyone else. Rather, it might be that both capitalism and the welfare state tend to weaken forms of solidarity that give meaning to life for many people, while offering nothing but money in their place.

Which is to say that while the Marxist revival is interesting enough, to become more relevant it needs to become a little more … reactionary.

It is actually true that, in John Locke’s bourgeois account of the development of the idea of property, God is replaced by money. After he gives the account of the human invention of value for little pieces of yellow metal—an ingenious overcoming of the natural and Biblical limits to personal acquisition, he never mentions God or his authority again. (He couldn’t shut up about God and Biblical revelation up until that point.)

There does seem to an emerging consensus among sophisticates today that non-libertarian conservatism—and authoritative religion in general—are “reactionary.” They have been discredited by “capitalism”—or economic and technological progress—and so are destined to have no place in the emerging future. A reactionary is nostalgic for a world that’s been surpassed by history and so can’t and, in truth, shouldn’t be restored. Unlike crabs, we dialectically materialistic beings can’t crawl backwards.

This anti-reactionary impulse is also why “liberal education” seems to be withering away. It has no place, our “disruptive” critics say, in meeting the challenges of the twenty-first century global competitive marketplace. On that point, most of our Marxist and libertarian economists seem to agree.

There are some so-called conservatives who do seem to be genuinely reactionary. They too readily accept Marx’s description of capitalism as a realistic account of the world in which we live. They think of themselves as living in a techno-wasteland and of freedom as having become another word, these days, for nothing left to lose. Identifying capitalism with America, they become anti-American and anti-modern and almost as revolutionary in their intentions as members of Marx’s proletariat.

To give these reactionaries the credit they deserve, they long and work for a world where it’s possible to be at home with the full truth about who we are as free, dignified, and relational persons. They’re repulsed, with admirably good reasons, with the utopian fantasies of the Marxists and the libertarians, even if they are more scared than is reasonable that they might actually become true. They might not be completely wrong, however, to see intimations of the possible idiocracy to come in the ways we already relate to the screen and to each other.

We true conservatives put the word “reactionary” in ironic quotes, because we deny the premises about history and the comprehensive explanatory power of economic analysis that it implies. We’re not about restoring some past world. But we think God, country, families, friendship, philosophy, theology, and love haven’t been and can’t be taken out by techno-progress.

So we don’t think liberal education and authoritative religion have become irrelevant; we still need them to live well as beings born to know, love, and die.

That’s why we even put “capitalism” in ironic quotes, because it doesn’t really correspond all that well, thank God, to the world we now inhabit. That’s not to say we’re not for a basically free economy and appreciate the benefits of technological progress. It is to say we think of free persons as much more than producers and consumers.

Peter Lawler is Dana Professor of Government at Berry College. He teaches courses in political philosophy and American politics.