Let’s be clear about one thing here: Rand Paul thinks he’s going to win in 2016. He has a vision for the party, but he is not running as an idea candidate. He is trying to win the election. He’s not running for Vice President. He’s not running to grow a movement. He thinks he can run, beat everyone, and be president.

In order to get there, he is deploying a unique approach to outreach – one that is designed to promote a certain type of cross-pollinating political appeal, one that is largely unfamiliar on the right, in order to broaden a coalition not around limited government ideas so much as around his uniquely libertarian positions on key hot button issues. In this, Paul’s Berkeley event – as much as his events in other supposedly unfriendly venues – is an example of how he’s making a pitch for people to identify him with specific issues (typically based in distrust of government) that cut across traditional coalition lines. It’s also an example of how he’s trying to do something very different than traditional Republican candidacies in the modern era.

Serious, politically engaged people on the right have a fairly well developed idea of what libertarianism looks like – and many of the smart ones don’t believe Americans actually know what libertarianism is, or what it stands for. The eloquent and savvy Kevin Williamson has a piece which distills this problem to its essence: that while people who voted for Barack Obama may cheer for Paul now, once they become more familiar with his message, they’ll reject him as an extremist.

It may be true that most Americans don’t really know what libertarian ideas look like. The media certainly doesn’t – for their narrow frame, libertarians behave more like modern socially liberal Republicans than classical liberals. To the media, libertarianism is only worth promoting if it primarily has to do with abortion and gay marriage (just watch: if as we expect Paul’s 2016 libertarianism isn’t that, they’ll probably dispute he’s even a libertarian).

Of course, Paul’s rise has relatively little to do with his positions on social issues at all. In truth, it’s in large part due to the rising distrust of government and big institutions, Paul’s message has the ability to puncture typical biases against any politician with an R after their name with constituencies who Republicans have traditionally ignored. This is why what Paul is attempting is actually far more interesting than just the promotion of a prospective 2016 candidate. What he’s attempting is an approach to politics adopted with great success by Barack Obama and Bill Clinton – one that targets particular issues to broaden his appeal and build his own personal brand.

As Jonah Goldberg and others have noted, since Ronald Reagan, the right has formed into an ideological coalition while the left has formed a coalitional ideology. Where the right has its three legs of the stool, the left has formed a coalition which gloms together the disparate interests of the middle aged school teacher, the wealthy Silicon Valley liberal, the Ivy League hipster, the environmental non-profit, and the third-generation blue collar union dad… even when their interests really don’t really align.

What Paul represents is a post-three-legged-stool reality for the Republican Party – a politician who recognizes that the party’s brand has been markedly harmed, the old ideological coalition is dying, and that the path to success may instead lie in creating a patchwork majority based on the varying faces, and unique appeal, of libertarianism.

Of course, there are pitfalls to this strategy. Putting forward the most palatable aspects of your ideology to the groups that care about each is smart politics. But is it objectively possible to sustain such a majority? The media wanted Obama to succeed with all the unbiased, even-handed coverage of screaming Beliebers. Is it plausible Paul will get the same treatment?

The fear for the right is that they won’t – and that Paul’s inchoate coalition will crumble under media pressure on other issues, or Paul will have to fudge on specifics to keep it intact. His views on marriage and life are traditional. As Williamson notes, the many faces of libertarianism include ones unpleasant for seniors (Medicare and Social Security), minorities (civil rights law), young people (student loans), poor people (Medicaid and welfare), and business elites (Fed policy, the gold standard, ending corporate welfare, and more).

The secondary problem is that this coalition Paul is forming is one built around himself, and his own unique brand of politics, as opposed to an attempt to make a broader case for the right over the left. You can understand why this is, but it’s a basic distinction: Jack Kemp spent a significant portion of his career making the case that Republicans could be good representatives of inner city minorities, not that only Jack Kemp could do that. What Paul is doing will not help another nominee in 2016, only himself. We can talk of “expanding the party,” but the more accurate reality is that he is trying to create a list of voter preferences that goes: Paul, Warren, Clinton, and so on.

Right now, Paul enjoys the luxury of every Senator – the prerogative to weigh in on issues of his choosing and avoid thornier questions. Executives have no such problem – they have to respond to the issues that come to their desk. In election years, front runners have the same challenge. Will Paul be able to withstand it? Or will he have to make peace with the New Deal, the Great Society, the federal Department of Education, fiat money, Civil Rights law, and the foreign policy establishment to get there?

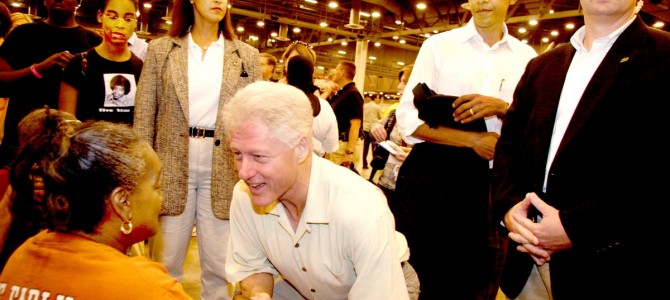

Yet the Clinton “all things to all people” model contains some hope for Paul’s approach. It was an appeal to the middle class in tax and regulatory policy. For Wall Street, it offered a lighter regulatory touch paired with an emphasis on free trade. To the hard hats, it offered Sister Souljah and welfare reform. To the feminists, it was Hillary at the policy forefront. It managed to build a coalition of middle class and elites and EITC.

What held this odd grouping together was Clinton’s particular gift of reptilian political skill, and a knack for shooting the moon. Can Paul replicate that? It’s a challenging strategy. It also just might be that Paul has the personal gifts to make it work.

Follow Ben on Twitter. Subscribe to The Transom, his daily newsletter.