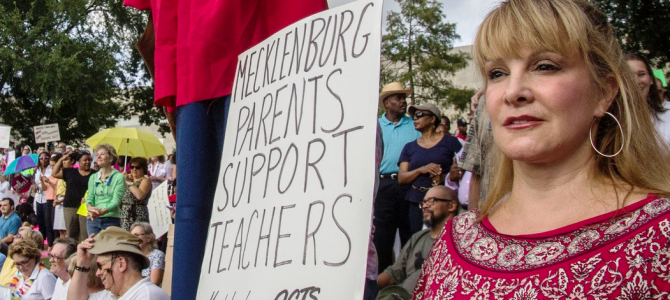

On and off for twenty weeks now, a diminishing troupe has gathered for “Moral Mondays” to protest the outcomes of North Carolina’s first Republican-led legislative session in 150 years. This spring, 2,000 or so people showed up for Moral Mondays protests at the state capitol, and more than 900 have been arrested for disrupting the legislature. On September 23, they numbered about 60.

Their grievances are many. A ThinkProgress blogger recorded protesters’ forecasts of ominous consequences for the poor, the environment, healthcare, education, the economy, students, women, and the disabled. (He seems to have left out puppies and sunshine.) Because of the protests, The Atlantic called North Carolina “the Wisconsin of 2013,” in reference to the circus of protests and recalls that accompanied mild restrictions on government employee unions in 2010. Even National Journal has taken up the cry, highlighting “conservative attacks on public education” within “the GOP’s plan to sabotage Raleigh’s successful growth.”

Are North Carolina Republicans decimating schools and the poor? Let’s take a look at the derided right-wing agenda, just in K-12.

Unusual Enrollment Spike

Raleigh, like the rest of North Carolina, is unusual for seeing more youngsters in recent years. In the past decade, school-age children increased 49 percent in Raleigh, the nation’s biggest jump. Most states are instead facing K-12 population declines, thanks to a declining birth rate nationwide. Census Bureau statistics indicate North Carolina has instead had an approximately 30 percent increase in school-age children since 2000. This puts the state in the enviable position of having to hire more teachers in an era when most states are cutting or will soon need to cut school employees because of declining enrollment. Not that you’ll hear that from school leaders. No, it’s moaning and groaning when so much as one dollar leaves their district, and moaning and groaning when their district has to expand.

School administrators in Raleigh blame a lack of money for their decisions to buy shopping centers and modular units to make classroom space. They’re asking voters to approve debt-fueled building projects this October to ease the strain. Taxpayers, then, might appreciate the state’s new voucher program, which lets kids leave public schools for empty spaces in private schools at approximately half the public expense. There’s an efficient use of resources, both tax dollars and school buildings. But public school administrators don’t seem to appreciate the help.

There are distressing anecdotes, like this from a North Carolina teacher who recently quit: “When I moved here and began teaching in 2007, $30,000 was a major drop from the $40,000 starting salaries being offered by districts all around me in metro Detroit, but it was fine for a young single woman sharing a house with roommates and paying off student loans. However, over six years later, $31,000 is wholly insufficient to support my family. So insufficient, in fact, that my children qualify for and use Medicaid as their medical insurance, and since there is simply no way to deduct $600 per month from my meager take-home pay in order to include my husband on my health plan, he has gone uninsured.” An excellent case for demanding that schools pay a living wage, right?

Piling On Administrators

The problem with education spending in North Carolina is not that there’s too little money to go around, however. The state spends approximately $9,000 per student, which is well below the national average of $13,000, but well above the lowest-spending state, Utah, at $6,000. Multiply that by the ratio of teachers to students in North Carolina, which is a teacher-pleasing one to just below fourteen, and you get $126,000 per teacher to spend. That’s more than enough for a nice salary and benefits package, especially in the school districts around Raleigh, which spend an extra thousand or two per pupil above the state average.

It’s also about four times more than a North Carolina teacher with up to five years of experience makes. The state teacher salary schedule, which local districts usually supplement and does not include benefits, puts a teacher with five or less years of experience at a $30,800 annual salary. Teacher pay maxes out in the schedule at $53,180 for someone with 36 years of experience or more. The average local salary supplement is approximately $3,500 per teacher.

So where does the rest of the money go? Well, there’s overhead. And boy, do North Carolina schools have overhead. For starters, North Carolina schools employ almost as many school administrators as they do teachers. The ratio of students to administrators is 1 to 15. While student enrollment increased 36 percent between 1992 and 2009, the number of non-teaching school staff increased almost twice as much: 61 percent, according to the Friedman Foundation. If administrative growth had just matched student enrollment over those years, every teacher could have received a $5,650 pay hike every year.

Some of this astonishing bureaucratic growth can be attributed, as in this Harvard University study, to a lack of market pressure on schools. Study coauthor Eric Hanushek says schools typically don’t make tough but necessary financial choices because they don’t lose money or market share for bad financial or educational management, unlike private enterprises.

As if to reinforce Hanushek’s point, Raleigh-area Durham County schools spent $3.5 million in federal Race to the Top (RTT) funds not on teacher salaries, but on iPads. You know, the same tool Los Angeles schools will spend $1 billion on but can’t figure why? Technology may be cool, but its record of improving K-12 education so far is, at best, spotty.

Regulations Strip Resources

But some pressure to hire administrators also comes from an explosion in government regulation in the past decade. For one, North Carolina was “lucky” enough to win $400 million from taxpayers in all the other states through RTT’s federal grant competition. This four-year grant amounts to 5 percent of the $7.5 billion North Carolina spends on K-12 education each year. Even so, the grant “created its own superstructure within the Department of Instruction,” says Bob Luebke, a senior policy analyst at the Raleigh-based Civitas Institute. RTT follows the federal pattern exploded by 2001’s No Child Left Behind (NCLB) of saddling schools with time-consuming mandates in exchange for a relative pittance. Among other things, RTT means every school district must develop new teacher evaluation systems, and the state must implement new plans for saving failing schools, although the recent evidence from such efforts nationwide shows they have essentially no effect. Even so, states have spent time and millions of dollars that could have gone to classrooms instead on contracts for consultants, largely ineffective professional development, and more bureaucrats to file more paperwork. Ohio also got $400 million from RTT, and several districts dropped the program because compliance costs are far above the stack of other people’s money they would get in return.

The same is true for NCLB, another source of administrative bloat that doesn’t benefit kids. This largest federal education law means 7 million hours of paperwork for U.S. schools every year, at an estimated annual cost of $141 million, according to the Office of Management and Budget. Small schools and districts have the same paperwork demands as large schools and districts, noted Loudon County, Virginia, superintendent Edgar Hatrick III in congressional testimony.

Just one regulation from the Office of Civil Rights caused his district to spend time “aggregating and disaggregating more than twelve categories of data, with more than 144 fields for each of our 50 elementary schools and 263 fields of data for each of our 24 secondary schools, for a total of 13,944 data elements. And this was just for one school district out of the 13,924 school districts in America.” This required 532 hours from Loudon County staff at an estimated cost of $25,370, or “82 instructional days away from students.” Even worse, most federal reporting requirements demand re-compiling data that schools already send the state, he said.

Proving they spent RTT funds according to their agreement with the feds will mean similar reporting requirements of all North Carolina schools. Each dollar that goes into paperwork is a dollar that is not reaching students. The teachers joining Moral Mondays protests might better direct their anger to Congress and the U.S. Department of Education.

Competing for Money

Along the same lines, K-12 spending necessarily competes for priority among other government spending. North Carolina spends between 32 and 40 percent of its budget on K-12. While the recession has meant tough times and therefore no money for teacher raises in the past several years, this budget year a $500 million cost overrun in Medicare spending wiped out lawmakers’ hopes of restoring teachers’ typical annual raises, Luebke said. As the population ages and more people receive government benefits from other taxpayers, K-12 spending will face even fiercer competition. Don’t forget: Old people vote.

Another structural problem with how North Carolina pays teachers is its antiquated salary schedule. Each teacher is paid like a 1950s factory worker, according to two main categories: Credentials and years on the job. Young teachers can’t earn more through excellent work, and teachers who move mid-career or from out of state often have to start over at the bottom of the pay schedule.

“Under the current schedule we pay great teachers and good teachers and mediocre teachers often times the same salary, and how is that fair?” Luebke said.

Studies have repeatedly shown that North Carolina’s salary schedule preferences older, more credentialed teachers over younger, less credentialed teachers, although being older and more credentialed has almost no relation to teacher quality. This spring, lawmakers took a first swipe towards addressing this by eliminating pay bumps for teachers with master’s degrees and phasing out tenure by 2018. Tenure typically prevents schools from replacing low-quality teachers with better ones. Eliminating it gives teachers the same job protections every worker enjoys under state and federal law. And research has long shown that teachers who earn master’s degrees are a cash cow for universities but don’t improve professionally. Ending the salary schedule gives teachers the individual bargaining power other professionals have, and treats them like people, not widgets.

North Carolina’s future looks brighter than many states, largely because of its bumper crop of kids. The more kids, the more future taxpayers to pay off the load of local, state, and federal debt Baby Boomers have handed them. But those Boomers aren’t gone yet, and their demand for government subsidies right as they get old and sick is directly at odds with taxpayers’ ability to send money to classrooms and tax relief for younger, working families. Given that face-off, expect future budget negotiations in North Carolina and around the country to embody rising social tension.

“In the first two years of this recession, ‘9 and’ 10, you have the same things going on where there all are these expected cuts, [but] Democrats were in control of all branches and the howling is nowhere near what it is now,” Luebke said. “They just feel compelled to rally their base on this. I understand what they’re doing, but it’s this selective indignation that gets you.”