Today marks the national day of mourning for President George H.W. Bush. For the past week, I’ve been catching up on the A&E documentary about his successor, “The Clinton Affair” – which features new interviews with Monica Lewinsky, Paula Jones, Ken Starr, and an assortment of journalists and former Clinton associates spread over six hours of television. For anyone young enough to have forgotten details about the Clinton scandal, it is an eye-opening documentary which reminds you just how scummy and unserious the Clintons were, and just how foul their media-devotees were in assisting in their partisan duplicity and craven use of power to further their agenda at all costs (The NYT’s Jill Abramson in particular comes off badly).

The documentary’s depiction of the crazy Clinton White House stands in stark contrast to the remembrances of the George H.W. Bush presidency that have been flowing since the weekend, and particularly the aspect of deep respect he had both toward the office and toward the responsibilities of being commander in chief. Yesterday I linked one of the few critiques of H.W.’s presidency that struck me as having any validity, from former CQ editor in chief and National Interest editor Robert Merry. Unlike the critiques lodged by the libertarians at Reason, the leftists at Slate, or the meandering mediocrities at The Atlantic – in an unconscionable piece that accused the former president of being “racially revanchist” – Merry at least sounds to me like the conservative critics of 41 in the early 90s. But it’s notable how weak that case sounds at a remove, when H.W.’s gifts for leadership are all the more apparent, and his weaknesses as a leader are clearly confined to surface-level decisions that ultimately proved his undoing.

Part of the complicated factor of assessing his tenure as president, capping an epic career of service to the country, is that the great legacy of George H.W. Bush, like his son, is the thing that didn’t happen. In the wake of 9/11, everyone in America assumed we would be attacked again, and with even more fury. George W. Bush’s policies prevented that. In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, everyone in America assumed that there would be wars to follow – wars over the reunification of Germany, over the nations within the sphere of Soviet influence, and more.

There weren’t, because George H.W. Bush’s policies and diplomacy prevented that. His use of American military might was confined and had clear goals. His diplomacy offered a peaceful respect on the one hand for our former foes, but clear lines of delineation between what we expected and would accept and what could not be done, popularity be damned. His demand that a reunified Germany continue as a member of NATO is a particularly clear example of this – unpopular as it was in Germany, but of the utmost necessity to global stability.

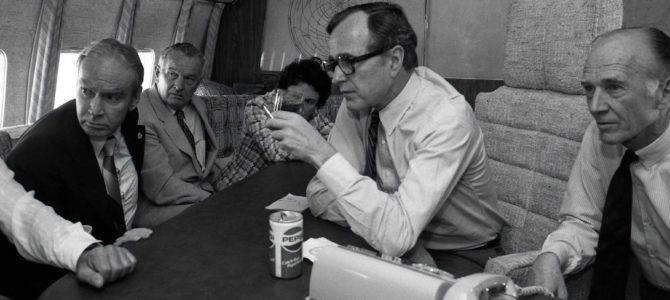

The late Peter Rodman, Henry Kissinger’s former assistant, wrote in Presidential Command that Bush’s administration “was the most collegial and smoothest run” of any modern presidency. “It had its share of policy quarrels and bursts of ego, but nothing resembling the high drama or low melodrama of its predecessors. This is because it was led by a president who was consistently the master of his brief, and whose personal engagement preempted bureaucratic warfare.”

“Awkward as he was in some circumstances, Bush had the natural gregariousness of the politician – even more so than the aloof Reagan,” Rodman wrote. “Coupled with his substantive knowledge, this gregariousness guaranteed that he would engage enthusiastically in personal diplomacy, picking up the telephone and taking charge of policy implementation himself to an unusual degree… ‘The mad dialer’ was the name he acquired among State Department officials who had to scramble to find out what he was up to. He wanted to be a hands-on president, and he was.”

The problem, as many within the administration came to believe, was that the president was operating within a cocoon maintained both by those looking out for his own interest and others with less admirable desires. As Bob Gates put it: “His weaknesses in foreign policy were reflections of his strengths. He was at times too patient and too forgiving of the ambitions and game-playing of both foreign leaders and some of his own people. He was at times loyal to some who did not deserve it or return it.”

In Hell of a Ride, John Podhoretz’s account of his time in the Bush White House, he lays the blame squarely on Richard Darman – who had denounced the “no new taxes” line as an act of “grossest demagoguery” – and the rest of the Three Ring Binder Guys who remained in key positions despite their steadily increasing disloyalty to the president and dismissal of conservative frustrations:

Like the ever-flattering, sweet-tongued eunuch, the Three Ring Binder Guy is there to ease the uneasy spirit of his superior. If a cabinet secretary suddenly wakes up in the middle of the night and thinks, ‘What the hell am I doing here? I don’t know what the hell I’m doing!’ he can call his Three Ring Binder Guy. And his Three Ring Binder Guy will assure him that he’s done a lot and is doing a lot more. Why, just look at this tab, and this one, and this. The binder itself is incredibly thick and unreadable, which is by design. Its purpose is to intimidate anyone who picks it up, to impress the boss with its sheer bulk and allow him to conflate the physical weight of the binder with the weightiness of his actions and policies. Three Ring Binder Guys use the three ring binder because every day it just gets bulkier and bulkier, more and more intimidating. It’s an egalitarian binder, too, because everything from the most serious matters to the most trivial literally weighs the same.

Much of the analysis of George H.W. Bush’s tenure this week has spoken to his obvious class, his much-respected character, and his seriousness in contrast to an unserious age. These personal aspects will in time return to the presidency. It is inevitable that they will, because the American people will demand it. They are so clearly deep human virtues unattached to ideological fealty that Americans have returned to them again and again in the candidates they seek to nominate.

What can be said of George H.W. Bush beyond the personal accolades is that as president, he was a man who did nothing by half measures. He was hands-on, engaged, and thought deeply and seriously about the purpose of the nation. He was on occasion given bad advice by those Three Ring Binder Guys around him and their ephemeral projects – like 43, he had a tendency to offer too much loyalty to those who did not necessarily have the knowledge or the character to serve him well. But this is no great sin, and hardly unique in politics.

And when reflecting on the presidencies that have followed, what emerges is a perspective on George H.W. Bush that ought to appreciate his deep and abiding manly qualities: devotion, service, and resolve. The media dogged Bush with the “wimp factor” moniker in an astounding example of their own self-loathing preference for the false bravado of Bill Clinton, with his sad lothario performance constantly seeking Peter Lawford’s beach house. They judged the World War II hero for looking at his watch, for trying to answer a woman honestly who didn’t understand the difference between the deficit and the recession, and fell for a president whose greatest skill was catching hold of an economic updraft and convincing the media he made it fly.

The era of Baby Boomer control that has followed in the decades since has shown how little quarrel one can have with George H.W. Bush’s old school approach to leadership – offering the nation what it has needed most at key moments in our history, the command of serious people brought forward for a serious time. In an era that has embraced unseriousness as a virtue, America needs it all the more. As they have done before, they will demand it again. Let us pray there are leaders like this to heed that call.