The images and stories now being reported from the southern border—families torn apart, children crying for their parents, parents with no idea where their children are—are disturbing and heartbreaking

The Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration enforcement policy has obviously created chaos along the border, tasking already overburdened federal agencies with the seemingly impossible job of taking into custody everyone—men, women, and children—caught crossing the border illegally. The number of children taken from their parents and placed in federal custody climbed to about 2,000 from April 19 through May 31, according to figures from the Department of Homeland Security. With border facilities overwhelmed, some teenagers are now being housed in temporary shelters outside El Paso.

But the reporting from the border has also been incomplete, misleading, and at times biased and emotionally overwrought. It’s no secret the mainstream media disagrees with Trump’s push to crack down on illegal immigration and tighten border security, but that shouldn’t excuse the lack of nuance and granularity in much of the reporting we’ve seen over the past week or so.

Illegal immigration and its attendant problems along the U.S.-Mexico border are vastly complex and defy easy solutions. With that in mind, here are four key aspects of the border crisis that the media has failed to report or adequately explain.

1. Prior To ‘Zero Tolerance,’ Families Who Crossed The Border Illegally Were Often Released

For a long time, the vast majority of illegal border crossers were single men from Mexico looking for work. Dealing with them was a fairly straightforward matter: most would be immediately deported to Mexico. It’s not that there weren’t families and unaccompanied minors also illegally entering, but they made up a small subset of illegal immigration.

Beginning in 2014, the situation changed. Large numbers of families and unaccompanied minors began showing up on the border in unprecedented numbers, many seeking asylum from dangerous criminal gangs in their home countries. Most of these foreign citizens were from Central America, not Mexico, and under a 2008 federal law designed to protect victims of human trafficking, migrants from noncontiguous countries have a right to a deportation hearing.

That meant the Obama administration had to figure out what to do with tens of thousands of unaccompanied minors and families that could not be quickly deported. Some were placed in shelters run by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) along the border, but because shelter space was limited, many more were placed with family members while they awaited hearings. Thousands have waited more than three years for a hearing, and thousands more have been ordered to be removed from the country in absentia (they never showed up for their hearing).

During this time, Obama was attacked from the Left for operating family detention centers in Texas and Pennsylvania. A New York Times editorial from July 2016 criticized the administration’s detention policies, saying the “privately run, unlicensed lockups are no place for children. Or mothers.”

A year earlier, a federal judge had ordered the administration to close two centers in Texas, citing the 1997 court settlement Flores v. Reno, which requires the government to hold children in the “least-restrictive setting” in places that are “licensed to care for children,” and to release them without delay to their parents or other adult relatives whenever possible. The Obama administration unsuccessfully appealed that ruling to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which upheld the district court’s ruling that Flores applied to all children, accompanied or not. But the court also said the administration could detain parents who crossed illegally.

The Obama administration responded to these rulings with a combination of deportation raids targeting criminals and a “catch-and-release” policy for families apprehended at the border, who would usually be issued notices to appear at an immigration hearing at some later date. This “catch-and-release” policy is what the Trump administration is trying to end.

To that end, Trump has invoked Flores as the reason for separating parents and children, saying the settlement limits what federal agencies can do with children brought here illegally and apprehended at the border. He blames congressional Democrats for failing to negotiate on an immigration bill that would solve the problem—although saddling Democrats with all the blame is disingenuous. Republicans have also failed to act on immigration (although now they say they’re ready to pass a bill to keep families together).

The media have been nearly unanimous in contradicting Trump, arguing that Flores does not force the federal government to separate parents and children, and that the administration has discretion in how it treats these families.

Both sides have a point. Flores does indeed limit how long, and under what circumstances, federal immigration authorities can detain children. But it only “forces” the separation of families if the parents are detained and prosecuted for illegal entry. In that case, families are separated because children can’t stay with their parents if the parents are in criminal custody.

Before Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy, families caught crossing illegally were often released within a few days and the parents fitted with an electronic ankle monitor to reduce the likelihood of them absconding. Back in March, when I was reporting on the border in McAllen, Texas, I met a number of people from Central America who were wearing an ankle monitor. Most planned to cut it off and throw it away when they got to where they were going.

2. Illegal Immigrants Who Are Released Often Fail To Appear At Court Hearings

Indeed, failure to appear at court hearings is a major problem in our immigration system—one the media is glossing over in its coverage of the border crisis.

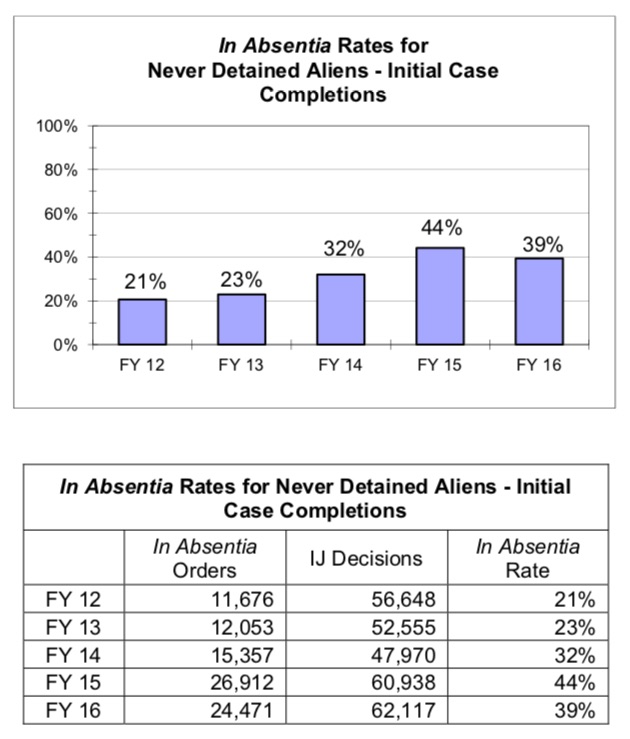

According to the DOJ’s Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR), the office that handles all immigration cases, a significant number of illegal immigrants who are released from custody never show up for their court hearings. Statistics from 2016 (PDF) show that “non-detained aliens,” which include those who were never detained and those who were released on bond or their own recognizance, failed to show up for court hearings in 39 percent of completed immigration cases—a 110 percent increase compared to 2012.

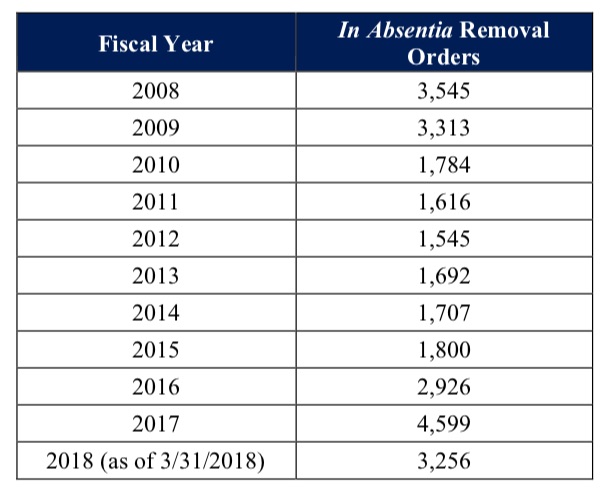

Since 2014, many of the families arriving from Central America have tried to claim asylum, saying they are fleeing violent gangs and dangerous conditions in their home countries. These asylum cases are a subset of the total number of cases ruled in absentia, and the most recent EOIR data available show a massive increase in the number of removal orders for asylum seekers issued in absentia—that is, cases where a migrant crossed the border illegally, applied for asylum, failed to show up at court, and was ordered removed in absentia. Note the sharp increase in 2017 compared to previous years, and the total for just the first three months of this year:

Of the nearly 100,000 parents and children who have sought asylum since 2014, court records show that immigration judges have issued rulings in 32,500 cases. About 70 percent of those were in absentia deportation orders.

The Trump administration has complained about the current asylum rules, especially the legal standard for “credible fear,” which supposedly allows foreign citizens to make meritless asylum claims. The White House recently said the number of those claiming credible fear has jumped to one out of every 10, up from one out of every 100 before 2011.

3. Our Immigration System Is Woefully Backlogged

By denouncing Trump’s policy of family separation and demanding that the administration keep families together, the media (along with a large number of lawmakers from both parties) are effectively arguing that families should be released while they await their court hearings or go through the asylum application process.

Whether they realize it or not—and no doubt many in the media and the Democratic Party fully realize it—this amounts to a de facto open borders policy given the state of our immigration system. According to EOIR data, there are more than 652,000 pending immigration cases for 2017 alone. That’s a nearly 100 percent increase from 2012, but not as many as just the first three months of 2018, with 697,777 pending cases.

The Trump administration has tried to tackle the backlog by hiring dozens of immigration judges and sending some to the border. But it’s not clear this has made much difference, or that it has reduced the backlog, as the administration has claimed. Julia Preston, an immigration correspondent with The Marshall Project, said this about the surge in immigration judges on an episode of This American Life back in January:

The Trump administration has said they’re pleased with the results of this surge of immigration judges, that it’s been a success. The director of the Justice Department agency that oversees the immigration courts said, and I quote, ‘mobilized immigration judges had completed approximately 2,700 more cases than expected if they had not been detailed.’ Essentially, he argued that judges who were sent to the border, about 100 of them in all, they completed 2,700 more cases than they would have if they’d stayed in their home courts. But that doesn’t take into account that sending judges to the border meant that at least 22,000 cases around the country had to be rescheduled in the first three months alone—perhaps for a year, as in Judge Pettinato’s Charlotte cases, or perhaps three years, like in Judge Burman’s courtroom.

We reached out to the Justice Department for comment. They didn’t respond to our request for an interview, but they did answer some questions over email. An official stressed that the backlog in immigration court is getting better. To be clear, they haven’t actually reduced the backlog. It’s still increasing. But they point out that it’s increasing at a slower rate. It was growing at over 3% per month when President Trump took office, and it’s less than 0.5% now. But it’s unclear if this change was because the Justice Department sent judges to the border or because of other efforts they’ve made to reduce the backlog, like hiring dozens of immigration judges.

Seen in this light, announcing a zero-tolerance policy when the system is so obviously overburdened was bound to create chaos. If the Trump administration wants to detain and prosecute everyone who crosses the border, fine, we can debate the relative merits of that policy. But to enact such a policy with an immigration bureaucracy that’s woefully backlogged and overburdened is simply reckless—an own goal.

By failing to build up the immigration courts and border facilities necessary to competently enforce a zero-tolerance policy, Trump has opened himself up to charges that his policy amounts to holding migrant children hostage in tent encampments, with all the emotional media coverage that goes with it.

4. Cartels And Human Traffickers Are Exploiting The Border Crisis

Perhaps the least-covered aspect of the border crisis is the role that Mexican drug cartels and human traffickers are playing. It’s hard to overstate the extent to which Mexico has become a failed society. As my colleague Ben Domenech noted earlier this week, 113 political candidates have been murdered in Mexico in less than a year. Just last week, a mayor running for Congress across the Rio Grande in Piedras Negras was gunned down while taking a selfie with supporters after a campaign debate. Fifty relatives of politicians and candidates have been killed, and 132 officeholders, mostly at the local level, have been threatened.

The cartels are massive business enterprises, and in recent years they have turned to human trafficking as a way to diversify their income streams as marijuana legalization has become more widespread in the Unites States. It used to be that migrant workers crossed the Rio Grande twice every day, once in the morning on the way to work and once again at evening on the way home. Not anymore. Border Patrol agents and law enforcement experts have told me that no one crosses the river anymore without paying. The going price is about $3,000 a head, even for small children.

So when the media report that migrant families are “rafting” over the Rio Grande, understand that they are being ferried across by human traffickers who are in it for the money. Often, these groups are sent across as part of coordinated effort to tie up Border Patrol resources so drug mules can ferry product across in another location, maybe just a few miles up or downstream. Border Patrol agents are aware that sometimes large groups are sent across to divert attention from drug smugglers, but there’s not much they can do about it.

One last thing to consider: it’s not just Mexican society that’s collapsing. There’s a reason we’ve seen a surge in illegal immigration from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala over the past four years: those societies are also collapsing, riven apart by organized crime and pervasive violence.

Whether or not the claims for asylum meet the legal definition, many of those showing up on our southern border are fleeing perilous conditions in their home countries. Whether we detain them, release them, or deport them, the flow of people from Central America is not going to stop as long as those countries continue to fall apart.

The Trump administration appears to be pursuing a needlessly cruel strategy to deter illegal immigration by separating families at the border. But the larger question of what’s driving illegal immigration is one that neither Trump nor the media nor Congress nor the American people are ready to confront. Until we are, we should expect the chaos on the border to continue, no matter who occupies the White House.