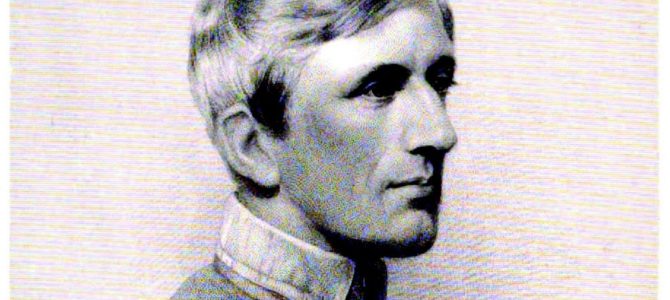

In our quest to improve our reading and discourse in 2018, we began with a consideration of Dante and his “Divine Comedy,” finding many nuggets of wisdom lodged within a single canto of the “Paradiso.” We now move forward half a millennia to our next sage: Cardinal John Henry Newman, an Englishman famous for converting from Anglicanism to Catholicism in the nineteenth century.

In particular, we will consider some of Newman’s opening remarks in his “Apologia Pro Vita Sua,” which recounts his religious journey into the Catholic Church.

Backstory to the ‘Apologia’

Newman’s conversion to Catholicism sent shockwaves through England. He had been a prominent Anglican cleric, and a leader of the Oxford Movement, a controversial clique within the English Church that sought to restore many Catholic beliefs and practices to Anglicanism.

When Newman wrote the “Apologia Pro Vita Sua” in 1864, he had been a Catholic for a number of years. Others followed his lead in swimming the Tiber. Many had questioned, if not openly attacked, his decision. None were more vocal or polemical than the Anglican priest Charles Kingsley, whose extensive writings against Newman demanded a response.

Newman took up the challenge, and the “Apologia” is the result, considered by many to be one of the great religious autobiographies in Christian history, ranked among St. Augustine’s “Confessions” and John Bunyan’s “Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners.” We will examine a number of prefatory comments Newman made before his narrative.

Charity Even When the Heat Is On

Early in his preface, Newman observes: “But I really feel sad for what I am obliged now to say. I am in warfare with him [Charles Kingsley], but I wish him no ill;… though I am writing with all my heart against what he has said of me, I am not conscious of personal unkindness towards himself.”

Newman’s perspective should be our own whenever we read or debate those with whom we disagree. He, unlike so many of us (myself included), who are puffed up with pride in the certainty of our own greatness and eager to put others in their place, evinces a sadness at having to be engaged in a war of words with another. We, in contrast, often cherish the fight, especially if a clever, strategic put-down is part of the fun.

Newman, by his acknowledgment, is indeed engaged in a battle, but he maintains a detachment that allows him to preserve a true charity towards his opponent. We need that same self-discipline and perspective when debating — the goal isn’t primarily to win, but to get to the truth, regardless of the victor.

Rein In Those Emotions

Newman continues by considering the factor most influential in influencing our opinion: raw emotion. He writes: “The habitual prejudice, the humour of the moment, is the turning-point which leads us to read a defence in a good sense or a bad. We interpret it by our antecedent impressions. The very same sentiments, according as our jealousy is or is not awake, or our aversion stimulated, are tokens of truth or of dissimulation and pretence.”

If ever there were an arrow shot directly into the center of our fickle, feckless hearts, Newman has let it loose from his proverbial bowstrings. How often do we judge an argument by anything other than the actual substance of the words and ideas?

We may, for example, see the author’s credentials and immediately dismiss his or her writings out of hand. I have witnessed many disregard my writing solely because my author bio says I’m a graduate student in theology at a Catholic university. Alternatively, we may encounter an article advocating gun control and presume whatever the author says is wrong simply because we oppose gun control. Then we see a link to an article on pro-life issues, and speculate that it is of no merit, because we are pro-choice.

Just as bad, we may begin reading something, determining the article’s worth solely because of some turn of phrase or sub-premise, rather than the piece’s main thrust. Whatever the circumstances, such sentiments should have little place in the considerations of anyone seeking to present themselves as “logical” or “rational.”

Drop The Self-Serving Rhetoric

Another problematic component of controversial discourse, closely related to emotion, is that of rhetoric. By this I mean not rhetoric in the classical sense, but using self-serving rhetorical devices that amount to little more than ad hominem garbage. Newman explains:

Controversies should be decided by the reason; is it legitimate warfare to appeal to the misgivings of the public mind and to its dislikings? Any how, if my accuser is able thus to practise upon my readers, the more I succeed, the less will be my success. If I am natural, he will tell them “Ars est celare artem [It is art to conceal art];’ if I am convincing, he will suggest that I am an able logician; if I show warmth, I am acting the indignant innocent; if I am calm, I am thereby detected as a smooth hypocrite; if I clear up difficulties, I am too plausible and perfect to be true. The more triumphant are my statements, the more certain will be defeat.

The literary force of Newman’s comments should bring a smile even to the most cynical of us. In describing how Newman’s opponent has characterized his own writings, the English Catholic cleric has offered a poetically English take on that tried and true Americanism: “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

No matter what Newman does — be it carefully articulate his arguments, express civility, or clarify his earlier statements — his opponent casts it all as just another Jesuitical flourish. This, in effect, applies “guilty until proven innocent.”

How often have we done the same in evaluating the arguments or writings of others? “Oh, that’s just typical leftist [fill in the blank].” “Talk about conservative equivocation and deception!” Whichever side of the aisle we’re on, if we employ such tactics, we’ve abandoned charity and reason for hand-waving rhetoric. Entertaining, maybe. Useful for truth? Hardly.

An American Identity Worth Achieving

Newman has far more words of his wisdom worth exploring in his preface and elsewhere. More than anything else, however, is his emphasis on truth free of prejudicial thinking. Above all, he seeks, as we should, that others might say of us, “he loved honesty better than name, and Truth better than dear friends…”

This is especially important when we are the ones vilified, misinterpreted, and slandered. As Newman declares, “He may cast upon me as many other imputations as he pleases, and they may stick on me, as long as they can, in the course of nature. They will fall to the ground in their season.” Rather than allowing ourselves to be provoked by every accusation, we need the self-restraint and self-confidence to take the higher ground.

We are capable of this, though it will require more effort and intentionality. Newman believed his fellow Englishmen capable of rising above their emotions for the sake of reason. He writes, “I think them [the English] unreasonable, and unjust in their seasons of excitement; but I had rather be an Englishmen, (as in fact I am,) than belong to any other race under heaven. They are as generous, as they are hasty and burly; and their repentance for their injustice is greater than their sin.”

Let’s let the same be true of us Americans — often excitable to the point of irrationality, but ultimately driven by a conscientious desire for what is true, a passion that will not relent until realized. Next time we will take up the third and last of our mentors, one such American who attained the heights of intellectual rigor and reason: Mortimer J. Adler.