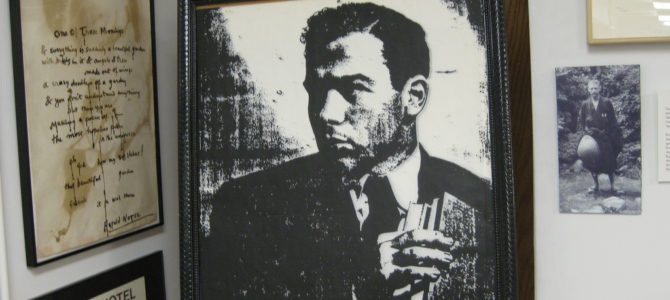

I read Jack Kerouac’s “On The Road” when I was 16. I made sure it was on top of my pile of books in the library during seventh hour. I wanted all of my classmates to see it because it wasn’t just a book, it was a totem of my sweetness, of the transient hermetic knowledge I was hip to.

As embarrassing as it can be to reflect on those days, I get it. I was imitating what I thought was a generation of innocents who simply sought pleasure at every turn. Identifying with the Beats and hippies was an excuse, a method for surmounting any responsibility that didn’t hold my full attention, a license to drop out.

Emulating the Beats allowed me to consider myself religious without ever setting foot in a church or reading anything. It allowed me to see virtue in selfishness and honor in failure. When I failed a class, I simply told myself that it didn’t matter because I was bored with all that. Y’know, I was too busy sitting alone in a cafe contemplating death.

I didn’t mind if I got fired from a job because I had come to value hardship over responsibility, because poor was cool. Being down and out was provocative, and I liked that. It’d all turn out fine in the end. I mean, Bob Dylan once said, “I read ‘On The Road’ maybe in 1957. It changed my life like it changed everyone else’s,” and things worked out pretty well for him.

Jack Kerouac Would Have Hated Me

So I rode the Greyhound bus. I quit jobs because, hey, it was sunny outside and I felt like going to the park where I could sit in the grass and pretend to understand James Joyce. But I was a kid. As I grew older, the effect of this worldview became more and more damaging. As my friends began climbing the economic ladder, I was still sleeping on their couches.

I talked a good game about the beauty of the world and the impossibility of growing up in America. I thought I was transcending something, but I was just being left behind. Kerouac’s work has been having this effect on people for 60 years, ever since “On The Road” was first published in the summer of 1957. And he hated that.

He spent the last 12 years of his life trying to escape from the people who saw his books as blueprints for living. Old paperback copies of his books advertise the “fighting, drinking, scorning convention, making wild love—zany antics of America’s young Beats in their mad search for kicks that adds up to one hell of a philosophy of life,” but that philosophy of life wasn’t his. Kerouac’s books are cautionary tales about the consequence of a life lived on the road. In an article for Esquire in 1958 Kerouac writes that the original Beat characters “vanished into jails and madhouses” and laments that while he is being asked to “explain the Beat Generation, there is no actual Beat Generation left.”

If Only We’d Really Read Jack Kerouac

In “Big Sur” Kerouac writes about meeting one of his beatnik groupies: “The poor kid actually believes that there’s something noble and idealistic and kind about all this beat stuff, and I’m supposed to be the King of the Beatniks according to the newspapers, so but at the same time I’m sick and tired of all the endless enthusiasms of new young kids trying to know me and pour out all their lives into me so that I’ll jump up and down and say yes yes that’s right, which I can’t do anymore – my reason for coming to Big Sur for the summer being precisely to get away from that sort of thing – like those pathetic five high school kids who all came to my door in Long Island one night wearing jackets that said ‘Dharma Bums’ on them, all expecting me to be 25 years old and here I am old enough to be their father…”

I must’ve read that passage a dozen times before I realized he’s talking about me, because I didn’t want to believe it. Although I genuinely adored his writing, I knew what Kerouac represented, and to be completely honest, I think I wasn’t so much reading his work as seeking passages to bolster my regard for him.

As embarrassing as it was for me to realize this, I respect his lack of hubris. He was a deeply religious, lifelong Republican, and he loathed the counterculture that arose in response to his writing. But he was also a broken and remorseful alcoholic undeserving of his role as a moralist, and he freely admitted it: “I like too many things and get all confused and hung-up running from one falling star to another ‘til I drop. This is the night, what it does to you. I have nothing to offer anybody except my own confusion.”

It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that lines like “the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time. The ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars” actually begin with “They rushed down the street together, digging everything in the early way they had, which later became so much sadder and perceptive and blank. I shambled after as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones…”

Madness Is Not Pleasant Nor a Virtue

The mad ones he so loved in youth were nothing like the “Castro-jacketed New Left” who “don’t believe in Western-style capitalism, private property, simple privacy even of individuals or families, for instance, or in Jesus or any cluster of reasons for honesty.” These had emerged from a commoditized misrepresentation of his work.

At least the mad ones Kerouac followed around early in his life realized, as he did, that “If it hadn’t been for Western-style capitalism, free economic byplay, movement north south east and west, haggling, pricing, and the political balance of power carved into the U.S. Constitution, I wouldn’t have been able or allowed to hitchhike half broke through 47 states of this union and see the scene with my own eyes, unmolested.”

To Kerouac the beatniks were irritating, but tolerable. It was the politicized hippie movement, the bohemians that succeeded the beatniks in which Kerouac saw something truly sinister. A few months before his death in 1969, Kerouac appeared on William F. Buckley’s “Firing Line” to discuss the hippie movement. There he said to icon Ed Sanders: “You make yourself famous by protest. I made myself famous by writing songs, and lyrics about the beauty of the things that I did, and the ugliness, too. You make yourself famous by saying down with this down with that, throw eggs at this, throw eggs at that. Take it with you. I cannot use your refuse, you may have it back.”

The Temptation to Impose My Truth on the Real Truth

For 60 years Kerouac has inspired college-aged kids dissatisfied with the so-called pressures to conform to a conventional lifestyle when most of his writing is a repudiation of liberalism. Kerouac offers us an honest look at the result of a worldview built on convenience, on my truth over absolute truth.

His books are filled with passages like “I am not ashamed to wear the crucifix of my Lord. It is because I am Beat, that is, I believe in beatitude and that God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son to it… So you people don’t believe in God. So you’re all big smart know-it-all Marxists and Freudians, hey? Why don’t you come back in a million years and tell me all about it, angels.” Yet to the campus Left he was a hero because they saw what they wanted—their truth. When Kerouac said “life is holy, and every moment is precious,” he meant it. It wasn’t fashion.

If he were alive today, Kerouac would almost certainly be shunned by the secular progressive culture his writing helped to create. By today’s liberal standards the “dropout who started it all” was a monster. He has been derided for not writing enough female characters. His love of black culture and jazz is now thought to be reductionist and even racist, even though he referred to African-Americans as “the essential American.” In modern progressive epicenters like New York and Berkeley—both cities Kerouac once called home—what was once the counterculture of the 1960s has become the conventional lifestyle that men like Kerouac are pressured to conform to.

Kerouac described his writing as “a tale told for companionship and to teach something religious, of religious reverence, about real life,” and he left us a trove of material that can do just that. We should take his stories for what they truly are: tragic love stories about a time in America when multitudes were imperfect, wondrous, and free to find meaning in their own way. They are love songs about the nobility of work, and cherishing even unrewarded effort over grievance. They are cautionary tales written by a flawed man who, as it says on his tombstone, simply “honored life.”