I found C.S. Lewis and The Narnian Chronicles at a pivotal time in my life: still too young to be cynical, but old enough to get the deeper symbolic meanings. I was 12, and ran through the books as fast as I could buy them with my babysitting money. I rejoiced at the coronation of Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy; I wept when Reepicheep sailed over the edge of the world; and I can still feel the pain and confusion of the bear in “The Last Battle” sucking his paws and repeating, “I don’t understand. I don’t understand!”

I feel like that bear quite often these days when I watch the insanity going on in the country around me. Always having been blessed with the grace of faith (although not always blessed with the grace of obedience), the Christian elements nestled within the Chronicles thrilled me.

As I got slightly older, I delved into Lewis’s nonfiction. Next came the Perelandra trilogy, which started my love of science fiction. Don’t turn up your nose—there is some great sci-fi hiding among “The Amazons of Samelon”-type trash.

Also around the age of 12, I found Madeleine L’Engle’s “A Wrinkle in Time.” As with Lewis, I did not stop at that first book, but went on to read “A Swiftly Tilting Planet” and “Meet the Austins,” following both the Murry and Austin families through each new novel. I was delighted when the characters from the two plots merged in later books.

Early On, A Model For My Own Life

L’Engle’s nonfiction grabbed me in my early twenties. I started with “Walking on Water: On Faith and Art,” followed by the Crosswicks journals. I was enchanted by the charmed life narrated in the journals. L’Engle was living my ideal life in both the Connecticut countryside and New York’s Upper Westside: sophisticated, intelligent, faithful, artistic; surrounded by friends and religious people: nuns, canons, and priests from many religious orders; hosting dinners that included talented artists, musicians, actors, doctors; and extended family, both biological and adopted in various forms. Hers was the model upon which I wanted to build my own life.

Lewis and L’Engle were the foundation of my early studies in Christian theology. I would eventually learn from more scholarly authors and the church fathers, the mystics and the saints, but the base that Lewis and L’Engle provided me was quintessential to my spiritual formation. Both also played a factor in my decision to become an English teacher and a writer. They taught me the power of the word.

Therefore, with great trepidation I picked up one of L’Engle’s journals in a secondhand book shop last week, “Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage” (Crosswicks Journal No. 4). When I read most of her nonfiction in the 1980s, I considered myself an enlightened compassionate liberal, although as I explain in my article “How I Realized I was Conservative,” I never really was. I was in my twenties, so forgive me. Now, would I still find her as enlightening as I once thought? Would I still want to model my life on hers?

Following Madeleine to New York City

I followed in L’Engle’s footsteps in 1985 when at the age of 24 I moved to New York City. I did not live on the Upper Westside, but in the then-trash-pit of Alphabet City, quite literally on the same block the film “Rent” depicts. There was nothing glamorous or romantic about it or the large cockroaches that fell from the ceiling with a thud or the cold shower water in January.

After that, I lived in the Bronx when it was still a war zone. Like L’Engle, I worked in theater, but behind the scenes as a scenic carpenter, lighting electrician, and stage hand, one of the few women in my position. It was a dark time for me. New York in the 1980s was terribly lonely, a deeply depressing and violent place, especially if you were a young woman who had little money and no family nearby.

At one point I was working on a theater production at St. John the Divine, the sublimely massive Episcopal cathedral on the Upper Westside by Columbia University. I was angry and melancholy. Appropriate to my mood, the production was in the dark, damp, unfinished crypt below the cathedral. The musty sand floor combined with New York summer humidity, the walls of enormous foundation stones that seem to make the very air itself heavy, and the sarcophagi of Episcopal bishops made it a dismal space in which to work.

The cathedral itself is an awe-inspiring monument full of sculptures and artwork, numerous chapels, and ceilings that disappear into the heights. There are multi-storied tapestries and a massive polished floor dotted with bronze medallions two to three feet wide, honoring pilgrimage sites and the miracles of Jesus. The school where my father taught had just such a medallion in the floor of the vestibule. He taught me to respect it, never to step on any such medallion. I intentionally stepped on every medallion on that vast floor on purpose. God had ticked me off, and I wanted him to know it.

The Day I Met Madeleine L’Engle

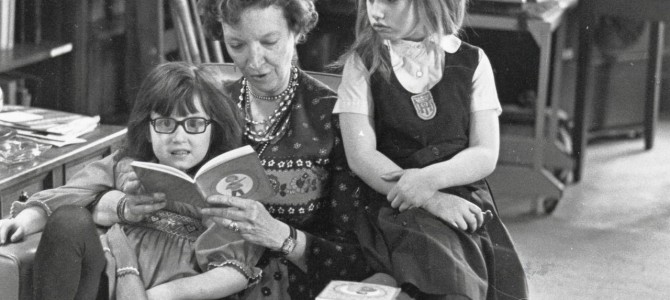

With much shame, I later read in one of L’Engle’s books her comments about the broken and disrespectful neighborhood children who did the same, although I doubt they did it on purpose as I had. L’Engle was working in the library at the Cathedral Close at the same time I was there. I did not know this then. She had been there for years. I wrote to her in spite of my shame, hoping that I might be able to take one of her writing workshops that she often talked about in her Crosswicks journals. She was hosting none on the East Coast that year, but she gave me her number at the library and invited me to visit her. This was apparently not unusual for her.

I accepted the invitation, but I was a tongue-tied fool too full of sophomoric bitterness. She was kind, unpretentious, and gracious. It was an honor, a cherished memory that makes me blush to this day at my awkwardness and missed opportunity to engage in meaningful conversation. Compared to the people in her fiction and nonfiction books who were extraordinary doctors, brilliant scientists, accomplished classical musicians, artist of all kinds, canons and abbesses, saints and saviors, I was very ordinary. It was not that surprising that I was mute.

I returned to Baltimore when I realized that I wanted babies, backyards, and barbeques with at least a few dogs underfoot. I didn’t think I was going to find that in NYC. Now, almost 30 years later, I have all of that in Baltimore, although my “babies” are now taller than I am.

My apprehension about reading this journal after three decades away from her was that the Madeleine L’Engle I rediscovered might no longer be the gracious, faithful, and creative mentor I once saw, but a predictable, politically correct New York liberal. I never once thought that in rereading Lewis I would suddenly find a liberal, feel-good social justice warrior; just a warrior. He came from a time when men were allowed to be men: strong, courageous, and sure, but civilized enough to be guided by morality, integrity, reason, and compassion. L’Engle was from a later era, the beginning of a time when Christians too often became blind social justice warriors full of “compassion” and destruction.

Rediscovering Madeleine L’Engle

In returning to her work, I found both L’Engles. The journal is of her 40-year marriage to Hugh Franklin, an actor most notably known for his part as Dr. Charles Tyler on “All My Children.” L’Engle’s narrative moves between the past and her present, the summer when Hugh was diagnosed with cancer. The title “Two-Part Invention” gives homage to the role of classical music in her life. Bach’s term two-part invention means “a short composition with two-part counterpoint.” L’Engle examines the counterpoint of life and death, past and future, love and loss intertwining.

The book is divided into three parts: “Prelude,” “Interlude,” and “Two-Part Invention.” As I read “Prelude,” a reflection on L’Engle’s childhood, early adult life in New York, experiences in theater, courtship by Hugh, and the burgeoning professional careers of both contrasted with the discovery of Hugh’s cancer, I felt encouraged.

The young L’Engle lives a disciplined and moral life. Unlike other bohemians of the time and of the theater, she does not sleep around or indulge in the relaxed moral atmosphere of the times. Instead, she works hard and studies hard. She recognized real talent and skill, the skill that comes with practice and hard work. Of her first apartment she says, “One of our roommates came because of the piano. She was a budding musician and filled the apartment with Beethoven, Brahms, and Bach, although after she came I only played when she wasn’t around.” L’Engle recognized that not all talent is equal.

L’Engle also seemed to have had sense about some very basic American ideas. Invited to actor Morris Carnovsky’s party in the early post-war era, she was repulsed by her host expressing his communist sympathies in raising his glass to the Communist Red Army. She recalls, “I didn’t know what was wrong, but I knew things were skewed. I felt embarrassed, then unclean.” Ironically, the same man also professed this capitalist idea: “He charged budding actors and actresses twenty-five cents a lesson on the theory that it is not good for us [the students] to get something for nothing.” As is so often true, he was yet another professed communist who exhibited little knowledge of communism, yet another “armchair Marxist.”

Her courtship with Hugh seems rather wholesome, as Hugh rejects women who throw themselves at him to embrace the more modest Madeleine. They date, they break up, they date again, and then they marry. It was a fairly uninteresting courtship. “Prelude” ends shortly after the marriage begins.

L’Engle’s faith runs deep throughout the narrative. For her, God is a real presence with whom she could talk, question, entreat, and find solace, but he is an unfathomable mystery at the same time. She struggles with how to interact with God throughout Hugh’s treatment, as procedure after procedure fails to halt the spreading cancer. During this period, three times she finds herself praying the Lord’s lament, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” in her Evensong. “The cry of the word made flesh, the total mystery of the human being,” she reflects. Each time, the burden of that cry leaves her struggling with feelings of betrayal as Hugh moves yet another step closer to death.

“Interlude” is but a single chapter. Perhaps this chapter stands alone because it is as much about beginnings in the iconic house in Connecticut, dubbed Crosswicks, as it is about their marriage.

The Lies We Tell Ourselves and Others

The third section shares the title of the book and covers the rest of her marriage while continuing to follow the struggles of Hugh’s failing cancer treatments. Here L’Engle’s presentation of her life seems to move into descriptions of an idealized life rather than life as it most likely was. It just didn’t ring true. When I first read the Crosswicks journals, I was an inexperienced twenty-something. I believed every word she wrote. But as a fifty-something, I am not so easily beguiled.

There are people who want their lives to be what they envision, not what they actually are, even if they are living good lives. I am not talking about those working towards change, but about those unable or unwilling to see their life as it exists. They create a different life in their minds or, as in L’Engle’s case, in public personae. I have come across more people like this than I care to admit, but I spent the first 16 years of my professional life in theater and the arts, so I suppose it is an occupational hazard. It pushed me away from the arts into a more practical life as a teacher.

I had a friend from college whom I adored. I was just a girl from Baltimore; she was from Tehran. Beautiful and cosmopolitan, she spoke Farsi, French, and English fluently. She could shift from one to another in the same sentence without skipping a beat. Half French and half Persian, she lived in Tehran until her mother and step-father fled to Paris before the revolution, then to Baltimore. Her father, who was related to the Shah, stayed in Iran to fight the Islamic Revolutionaries.

She had friends all over the Middle East, Europe, and America. They were the children of ambassadors and diplomats. She introduced me to people in the arts, theater, and film. We spent weekends in New York and DC among the young, beautiful, and international. It should have been enough for her to feel confident in herself, but it wasn’t.

After some time together, the threads of her stories started to unravel. Plans to travel to France fell apart at the last minute when our place to stay where everyone loved her evaporated. Friends often did not seem quite as remarkable as she described. She would introduce me in ways that were factually true, but were painted much brighter and shinier than the reality. I began to realize that her whole world was this way. I learned not to trust her so much. Sometimes I sensed her disappointment because life didn’t match what she had created in her mind. She exaggerated so often that she didn’t actually know what was real or fantasy, making all reality a disappointment.

I began to recognize this trait in L’Engle’s journal, as I had already noticed it in her fictional characters. Her life seemed too fabulous: full of the famous, of sunshine, children, dogs, and gardens, full of loyal, highly intelligent, extremely talented people from all over the world who just loved her so much.

I had been disappointed that my life had not matched L’Engle’s. I wanted to live a good life. I did not strive for fame and riches, but for integrity, family, friends, and faith. Things don’t always work out: divorce happens, friends betray you, and jobs don’t always lead to offers of better jobs and the undying respect of your peers. In other words, my life has been mostly normal. I suspected that L’Engle’s life was less charmed than her journals present.

Meandering Between Reality and Fantasy

The New Yorker article “The Storyteller: Fact, fiction, and the books of Madeleine L’Engle,” by Cynthia Zarin, confirms this. Zarin, a poet in residence at St. John the Divine, got to know L’Engle. Zarin writes, “Indeed, L’Engle’s family habitually refer to all her journals as ‘pure fiction,’ and, conversely, consider her novels to be the most autobiographical …” L’Engle’s daughter Josephine Jones’s reaction to “Two-Part Invention” was “Who the hell is she talking about?” Maria Rooney, L’Engle’s adopted daughter, calls the journal “a lovely fairy tale.”

Even more disturbing than feeling that I was perhaps duped all these years was reading what L’Engle said about her children versus her fictional characters: “We didn’t have a large family, and that was perhaps just as well; my characters are more alive to me than the people they are based on.” I cannot imagine ever feeling that fictional characters are more alive to me than my own children or husband. Her marriage, rather than being a 40-year love story, was instead at times a struggle: Hugh’s heavy drinking and infidelity took its toll. None of this is evident in this journal that supposedly explores their 40-year marriage.

Her lines between fiction and reality are so blurred that not only do real people become fictional characters, but fictional characters become “real” people. I first encountered the character Canon Tallis in L’Engle’s novel “The Arm of the Starfish,” then encountered him again in “Two-Part Invention.” I thought she had put a real person into the fiction, when she had in fact put a fictional character into a “real” narrative.

Additionally, L’Engle manages to hit on many of the burgeoning PC topics of the time: the environment, global citizenship, beauty in all cultures no matter how brutal, and so on and so on. Did she know she was an early adopter of politically correct liberal thinking, or was she just trying to look so very compassionate and enlightened to her readers, or perhaps just to herself?

Overall, the book was a disappointment, and I am unlikely to reread any of her other nonfiction titles. Her daughter, Maria, had this to say about her mother’s novels and journals, which often did not portray Maria and her siblings in a favorable light: “No, I’m not filled with bitterness now. She’s such a storyteller that she gets confused about what really happened.”

Neither am I bitter. L’Engle was an important part of my life’s journey. I may have outgrown her, as we are wont to outgrow our teachers; nonetheless, she provided me an invaluable element in my faith journey. She approached God with joy, with trust, sometimes with doubt and challenge, but she taught me to approach God with my whole imperfect self. Yes, we outgrow our teachers, but that does not negate what they taught.

I seem never to outgrow Lewis, however. Each rereading of his work leads me to new understandings and insights. I suspect I will never feel that I have gotten all I could from Lewis. But I needed both L’Engle and Lewis to become who I am today. It doesn’t matter that L’Engle has become fully and imperfectly human to me. I love her in spite of her flaws, as God loves each of us.