I hope to take at least a few weeks off from work when I give birth to my first baby in October (Lord willing). And I don’t expect a minute of that “time off” to be about me. But Meghann Foye, explaining her “meternity” advocacy to Anna Davies at the New York Post, seems to think maternity leave is just that:

As I watched my friends take their real maternity leaves, I saw that spending three months detached from their desks made them much more sure of themselves. One friend made the decision to leave her corporate career to create her own business; another decided to switch industries. From the outside, it seemed like those few weeks of them shifting their focus to something other than their jobs gave them a whole new lens through which to see their lives.

She says childless women should get “meternity” leave, to discover themselves, find relief from nine-to-five “burnout,” and figure out how to “advocate for me.” Except that “something other than their jobs” they shifted their focus to was not themselves (except in the sense that, physically, most women can’t just hop straight from hospital bed to office chair), it was a tiny, totally helpless new life that needed nurturing. To compare maternity leave to the sort of mid-career “gap year” (or month, or quarter) millennials have popularized is nothing short of an ignorant insult to mothers.

Babies Are Hard, Valuable Work

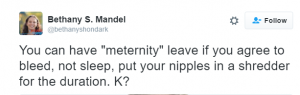

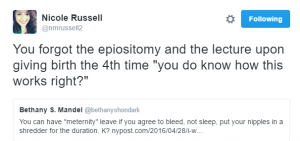

Yes, most of these working women choose to have babies, so to the childless coworker three months out of the workplace simply because you chose to become a parent may seem unfair. But maternity leave is no self-reflective picnic by the lake. As other Federalist women have tweeted:

And:

“Time off” is a misnomer for maternity leave. It may be time away from your professional occupation, but isn’t a vacation. For new moms, it’s learning a whole new job, a critical one you can’t ever quit, in a matter of weeks. Not to mention, most pregnant women must suffer through two to three months of morning sickness, random intervals of cramping as your ligaments stretch to accommodate your growing uterus, and four to six months (give or take) of feeling like a bloated whale, just to get to the birth.

Where is my maternity leave for that? Then there’s the delivery, which could last for several hours and might involve surgery. And then you’re a full-time parent, even before your body has recovered from generating an entirely new human life.

Mothering Is About Serving Others, Not Me

Foye argues women need time off from work more than men: “recent research suggests that women may experience [burnout syndrome] at greater rates; researchers postulate that it’s because women (moms and non-moms alike) feel overloaded by the roles they have to take on at work and at home.”

She does not cite any particular study, so the argument that childless women feel as overloaded by “the roles they have to take on at work and home” as mothers do is questionable at best (see this 2010 meta-analysis, which finds gender differences in burnout are exaggerated). While we’re comparing the sexes, it’s worth noting that Foye, who ostensibly sees “meternity” as a tool for female empowerment, is basically admitting that women need more time off for doing the same job as a man, without the extra responsibility of being a mother.

Perhaps this inequality is based in the idea that “Women are bad at putting ourselves first.” That may well be true. She goes on to say, “When you have a child, you learn how to self-advocate to put the needs of your family first.”

Except Foye is misusing the term “self-advocate” for something that really means advocating for the benefit of your family, whether directly or indirectly. You may see it as “self-advocating” if a mother leaves at 6 p.m. instead of 7 p.m., like her childless coworkers, to spend some time with her family before the children go to bed, or to pick a child up from daycare. That may directly benefit the mother, or she may be pushing something off until the next day she’d hoped to accomplish today. Either way, she’s making that decision based on family dynamics, not purely her own needs and desires.

To learn how to say, “no” to extra tasks and responsibilities when you feel you can’t handle it is an excellent skill. To learn to take breaks to refresh your mind is a good habit. Even occasionally punching out a little early when a friend is in distress shouldn’t need additional justification (Foye claims a friend needing a margarita after being stood up for a date and picking up a kid are equally valid excuses for leaving before the usual time). But Foye is hoping the “self-advocation” she sees in new mothers paves the way to equivalence between “maternity” and “meternity.”

It doesn’t work. As long as “meternity” is about me and me alone, what is learned will stand in contrast, not comparison, to the advocacy she’s observed in new mothers.

Personal Growth Comes from Self-Sacrifice, Not Self-Indulgence

Regardless, if you want a “gap period” to “find yourself,” petition your employer on the basis of how your time off will enhance your work. If you have such high value with your organization that your boss green lights a “meternity” leave, perhaps you’ve earned it.

But don’t insult mothers by pushing the self-centeredness so typical of millennials into the maternal framework, into a word that indicates self-sacrifice, a profound commitment to another life, and caring beyond yourself for the next generation.

“Meternity” is an asinine attempt at squeezing extended me-time out of employers by downplaying the real work involved in mothering a new child. Motherhood is at once a choice and a sacrifice, chaotic but proper, grueling work but bearing immense joy. This blessing, with all its burdens, comes not through time spent in self discovery, but in stepping outside yourself, in the willingness to break your body to create new life, in caring for a new, tiny, helpless baby who knows nothing of your insecurities, big plans, or fatigue.

None of this is meant to shame childless women. History has produced many great women who weren’t mothers. It doesn’t make a woman’s life any less valuable. But Foye shouldn’t wonder at the new confidence and security of mothers returning from maternity leave. Such confidence should be expected from those who have spent an intense period learning to put another life first, in “advocating for family,” as Foye put it.

This doesn’t only come through parenthood—I have seen the same effect in friends who returned from mission trips. I’m glad Foye felt her gap period was fulfilling, and that it made her a better person. However, to expect or demand extended time off paid employment focused on “living on my own terms and advocating what works for me” to have the same effect on one’s character, confidence, and outlook as giving birth and caring for a newborn is to profoundly misunderstand maternity leave. That’s because maternity is not about me.