“You know of course that we could never really be friends… Men and women can’t be friends, because the sex part always gets in the way.”

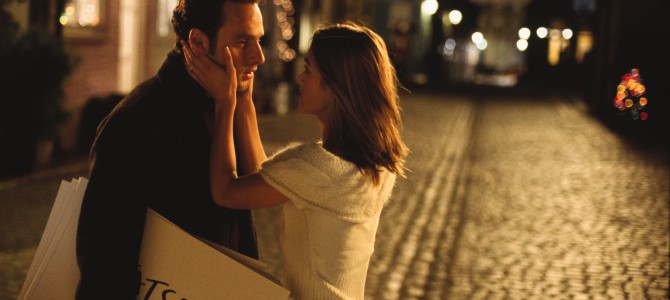

That’s from the 1989 romantic comedy, “When Harry Met Sally.” But you already knew that. It’s a famous movie and a famous line, and in the 25 years since Nora Ephron’s classic swept the box office, people still love this hilarious and heartwarming tale of true friendship melting into true love.

Partly, that’s because it really is a great movie. But it also speaks to a dearth of more recent romantic hits. Film critics have been scratching their heads and trying to explain the death of the rom com, most recently in this post-mortem at The Daily Beast, in which Andrew Romano argues that streaming and cable TV have forced Hollywood to move all its eggs to the big-effects basket, banking on foreign markets to help them turn a profit. Explosions translate into every language. Snappy dialogue, not so much.

It’s an interesting argument, but there are a few glaring holes. As Romano himself admits, romantic comedies haven’t just gotten scarcer. They’ve gotten worse. Scanning over the lists from recent years, a new theory forms: perhaps couples stopped going to rom coms because they just weren’t very good? Romano accuses Matthew McConaughey of trying to “destroy the genre singlehandedly” by spending a decade making unwatchable would-be romances.

I fully agree that “Fool’s Gold” and “Failure to Launch” were atrocious, but here’s the thing: McConaughey has since proven himself to be a great actor. He’s also tall and handsome and has a winning smile. If Hollywood couldn’t turn McConaughey into the next Cary Grant or Clark Gable, that might say something about Hollywood. Or maybe about the wider culture in which a good love story has grown so very hard to find.

What’s changed in a quarter-century? Quite a lot, as it turns out. Romantic comedies are still among the cheapest films to make, and Hollywood will always be glad to capitalize on goo-goo eyes and melting hearts. But when it comes to true love, the soil is a bit stonier now than in days of yore. Re-watch “When Harry Met Sally,” and notice two cultural trends that stand in stark contrast to today’s prevailing views.

Trend One: Promiscuity Is No Longer Chic

The first concerns the relationship between sex and marriage, particularly among the educated upper class. Although the movie self-consciously cultivates an air of old-school charm, it could never be mistaken for a bona fide 1950’s film, because it’s filled with casual sex. The opening scenes show us a young, newly-acquainted Harry and Sally discussing the various sexual encounters of their college years. Later on, twenty-something Sally (Meg Ryan) cohabitates for five years with a man who doesn’t want to marry her, while newly-divorced Harry (Billy Crystal) embraces the one night stand with a desperate enthusiasm. Sally’s best friend, Marie (Carrie Fisher), is a serial mistress, perpetually attracted to married men. Quite obviously, sex is not reserved for marriage in the world of Harry and Sally.

Ultimately, the film presents marriage in a positive light, and although parenthood isn’t the focus, I can still remember watching it with my college roommates and being moved by the scene in which Sally describes her epiphany concerning the shallowness of the cohabitating lifestyle. (She’s in a taxi playing “I Spy” with a friend’s child, and the little girl looks out the window and chirps, “I spy a family.” Sally starts to cry, goes home, and breaks up with her boyfriend.) Still, it’s odd to be shocked by the sex while watching an “old movie.” Partly that happens because the film treats somewhat-serious sexual depravity in a lighthearted way. But it also seems strange because Harry and Sally are successful, educated urban professionals, and in 2014, we associate that kind of promiscuity with a different socioeconomic class.

This is one respect in which richer and better-educated Americans have gravitated back towards a more traditional moral outlook in the quarter-century since Harry and Sally. Though the poor and less-educated have embraced it with enthusiasm, cohabitation is no longer chic among the elite and upwardly-mobile. Attitudes towards adultery are also more negative than in days of yore. College students may still fornicate in depressing numbers, but it’s unlikely that a modern-day romantic comedy would present a sympathetic and basically respectable character as a serial adulterer. It’s even more unlikely such a character would be given her own fairytale ending, complete with a devoted husband. As a late-eighties production, “When Harry Met Sally” documented the disordered sexual mores of the educated upper class just as they were beginning to outgrow them. Thus, the movie is actually somewhat antiquated in its cavalier libertinism.

Trend Two: Homosexuality Becomes A Stereotype

On other fronts, however, the weary march of sexual progress has continued apace, leaving “When Harry Met Sally” as a charming relic of a more innocent past. Indeed, the movie that (by common consent) revolutionized the rom com now feels almost like its swan song. Not for long would comedies be permitted to bask so unapologetically in the wonderful absurdity of sexual difference.

The term “swan song” might seem a bit hyperbolic, because Hollywood will be dark and shuttered by the time it has completely finished with heterosexual romance. Still, the fact remains that Harry and Sally stepped into the twilight years of widely-sanctioned heteronormativity. By the time “Clueless” was made in 1995, it was necessary to offset the hyper-stereotyped gendered characters with an equally-stereotyped (but also attractive and lovable) gay friend. Moving on through nineties hits like “My Best Friend’s Wedding” and “As Good As It Gets,” the gay friend was just one of many devices directors used to signal that they weren’t wedded to the trite, cookie-cutter stereotype of Boy Meets Girl.

And so the rom com went into decline. It was fairly inevitable once romantic love devolved from Boy Meets Girl into Two Or More People Doing Something Unspecified, Which However Is Deeply Meaningful To Them. Heaven help the scriptwriter who tries to pull a heartwarming love story from today’s morass of politically correct romantic ideals.

The reason we love romantic comedies is because they present us with a new variation on a timeless script that we all understand to be foundational to human life and society. When a comic story is implicitly underwritten by our recognition of the real significance of romantic love, even the most noxious and grimace-inducing sentimentality can take on certain shades of deeper meaning. That is possible because we know that falling in love really is something that characteristically happens to the young and foolish (so, people who may actually be charmed by candy hearts and lacy teddy bears), but that turns out to be far more significant than they themselves appreciate. Young lovers may be idiots, but they aren’t entirely wrong to assert that there is something eternal at the core of the gooey feelings. It is the seed from which future generations may spring. And in that sense, the Boy Meets Girl story really is the story of us all.

But we’re not supposed to talk about stuff like that here in the 21st century. It makes people in non-traditional family arrangements (are we still allowed to call them that?) feel bad. If we go around suggesting that Boy Meets Girl stories are somehow better or more meaningful than stories about boys meeting boys, or girls meeting girls, or two girls meeting another girl and glomming themselves all together the nation’s first legally-cemented “romantic committee,” that might seem kind of judgmental.

So Hollywood moved away from heteronormativity, and romantic love got whittled down to a subjective collection of feelings whose meaning and larger significance was completely individualized and almost infinitely adaptable. That left film makers with an ever-shrinking portfolio of jokes and references on which to improvise. Comedies got less funny, and love stories became weirder and less heartwarming.

Test This Hypothesis

By the time we get to the crass and insipid “Love Actually” (2003), romance is presented as nothing more than a completely idiosyncratic spark of synergy between Romantic Partner A and Romantic Partner B. (We were mostly still into couples in those days, but obviously that too is subject to modification.) Although it tries to make up for its shallowness by weaving together multiple love stories, “Love Actually” is boring and (ironically) completely foreign to the actual human experience of falling in love. If people want their love stories to be completely individualized, they might as well write their own.

Against this backdrop, it’s almost heartbreaking to return to a satisfying comedy like “When Harry Met Sally,” and recall that just a quarter-century ago it was still permissible to make a movie like this. Just to recapture that romantic high, let’s return for a moment to the above-quoted scene in which the brash 22-year-old Harry explains to skeptical Sally how men and women can’t really be friends “because the sex part always gets in the way.” Here’s the bit of dialogue that ensues after Harry makes his outrageous claim:

Sally: That’s not true. I have a number of men friends and there is no sex involved.

Harry: No, you don’t.

Sally: Yes, I do.

Harry: No, you don’t.

Sally: Yes, I do.

Harry: You only think you do.

Sally: You say I’m having sex with these men without my knowledge?

Harry: No, what I’m saying is they all want to have sex with you.

Sally: They do not.

Harry: Do too.

Sally: They do not.

Harry: Do too.

Sally: How do you know?

Harry: Because no man can be friends with a woman that he finds attractive. He always wants to have sex with her.

Sally: So, you’re saying that a man can be friends with a woman he finds unattractive?

Harry: No, you pretty much want to nail them too.

Sally: What if they don’t want to have sex with you?

Harry: Doesn’t matter because the sex thing is already out there so the friendship is ultimately doomed and that is the end of the story.

Sit back for a moment, and allow yourself to be amazed by the brazen judgmentalism of this scene. Its humor lies in the cool, clinical manner in which Harry approaches an obviously sexy topic. By Harry’s own argument, he must want to have sex with Sally; nevertheless he breaks down the ramifications of his claim with an almost ruthless, professorial exactitude, analyzing the proposed exception cases and ruling them out one by one. But for all his apparent rigor (and despite Sally’s eagerness to disprove his thesis), the topic of same-sex attraction never comes up. We aren’t even offered a cursory dismissal. (“Your friends aren’t gay, are they?”) Harry and Sally may be unapologetic late-seventies libertines, but in their universe, men are attracted to women, and women to men. That’s it. Harry’s ironclad rule depends upon it.

If you think that the film as a whole (if perhaps not that particular scene) could survive without the heteronormative assumptions, I’d invite you to watch it again and note how completely the drama and jokes all revolve around the assumption that the sexes are fundamentally ordered towards one another. Obviously it’s a cornucopia of gender stereotypes, but even beyond that, the central narrative falls apart without the foundational assumption that heterosexual attraction is a defining part of the human experience. “When Harry Met Sally” invites us to compare the straightforwardly Platonic experience of same-sex friendship to the more complicated adventure of opposite-sex bonding. Does that make sense in a world where anyone can be attracted to anyone, without judgment or moral difference? If we were to build off of Harry’s theories today, we would find ourselves exploring the rather depressing question of whether anyone can be friends at all.

All Aboard The Cultural Guilt Trip

I’m not sure whether to be amused or just saddened by the number of liberal friends who have remarked to me on how much they still love this movie, with a “they don’t make ’em like that anymore” wistfulness. It’s true. They no longer make movies like that, and we’re only permitted to only enjoy the ones that exist with the benevolently patronizing eye of people who assume that they have achieved a higher, more enlightened perspective. But if they were honest with themselves, these friends might have to acknowledge that they enjoy the film in a guilty-pleasure sort of way, as a throwback to a time in which romance had some recognized meaning that went beyond the navel-gazing soliloquies of the particular people involved. We’re far enough away from Harry and Sally to miss them, but close enough to retain some cultural memory of a time when the attraction between a man and a woman was understood to have a unique significance that other pairings couldn’t replicate.

If we flash forward another 25 years, what will today’s children think of “When Harry Met Sally”? I see this as a genuinely open question. Our ideals and mores could shift again, such that the gender-confusion of 2014 seems as strange to my children as Harry’s promiscuity looks to me. Perhaps our era will stand out as the benighted period in which people were utterly befuddled about love. Or, it’s possible that another quarter-century will give those cultural memories time to fade, such that the next generation finds the romance of Harry and Sally confusing and strange.

The question remains to be answered. Whatever the answer is, however, it will say something significant about the kind of world we will have built. Far more is at stake here than the future of the rom com.