While driving around Richmond the other day, I noticed, on the back of a car, a remarkably candid bumper sticker: “Humane meat is yuppie bullshit,” it claimed, and advised the reader to “ask any cow” to confirm this.

Judging by the license plate above this profound eight-word manifesto, the driver of the vehicle was an adherent of straight-edge veganism, a philosophy which, if you’re not in the know, combines the absolute worst aspects of both Jainism and alternative music: straight-edge vegans consume no meat (indeed, no animal products at all), drink no alcohol, and obsess over a preachy sub-genre of hardcore music that, to any reasonable observer, is patently unlistenable. You will know if you ever encounter one of these mosh-happy latter-day Temperance Leaguers, if only because you will remember the fervency and the tiresome moral zeal with which they endure their uninspiring diet and their atrocious music.

But back to that erudite bumper sticker: “Humane meat is yuppie bullshit.” The logic being, of course, that no meat can be “humane,” if only because eating meat involves killing animals, and killing animals is allegedly wrong. There are a great many interesting and compelling arguments in favor of vegetarianism, and maybe (maybe) even one or two to be made in favor of veganism; nevertheless, there are many more arguments in favor of eating animals, and they are better than the ones the vegetarians and vegans make. Humans will probably always eat animals, and this is, in the end, as it should be.

But it remains a valid question as to how humans shall eat the meat they will inevitably consume, and in this regard I will disagree with the percipient slogan to be found on the vegan bumper sticker: “humane” meat is great, it is ethically logical, and it should be what you’re eating if you’re eating animals.

What Is ‘Humane Meat’?

First, let’s define what “humane meat” really means. The definition changes a little bit depending upon the animals, but for nearly all farm livestock it will mean a life spent entirely on pasture (aside from the short trip to the slaughterhouse), with abundant room to move and engage in habits and tendencies specific to its evolutionary biology. That’s a mouthful (meat always is), but it’s a fairly accurate summation of what my brother and sister-in-law refer to as “happy meat.”

One must be so specific because a fairly successful advertising campaign utilizes clever marketing language such as “all natural” and “farm fresh,” utterly meaningless phrases, to trick you into thinking you’re getting something you’re not. Shopping for price is always wise; shopping against hucksterism should be encouraged, as well. If one is committed to eating humanely, one needs to be as judicious a customer as many companies wish you not to be.

What would this look like in practice? Taking as an example the lovely farm outside of Richmond from which I get most of my meat and dairy, this means beef and dairy cows on grass for their entire lives, eating from the same; laying hens and meat birds on grass as well, fed from both the pasture floor and the grain supplement they receive; and pigs both wallowing in paddocks and wandering in a nearby forest (if you’ve got one of the latter). These kinds of farms are invariably local, which means you’ll probably find most of this kind of meat at the nearest farmer’s market.

There are a number of truly excellent national suppliers from which you can order this type of meat in bulk, if you’ve no good farm nearby, but buying local from the market is easier, and more viscerally appealing: a great deal of ink has been spilled singing the praises of “getting to know your farmer,” but truthfully, there really is something to be said for it. There is a reason we feel so special when we personally know the chef who’s preparing our food, after all—then, too, there is a reason your mother’s cooking tastes so uniquely good.

Isn’t This Some Sort Of Gimmick?

The $64,000 question, which invariably and appropriately arises, is: Why should we eat this way? It is more expensive, after all, and while there are many more farmers’ markets than there used to be, they are still less convenient than the nearby supermarket or Wal-mart, the latter two of which offer a greater abundance and variety of meats—of foods in general—than humanity has ever known. Why give up getting your meat as conveniently and as cheaply as possible?

Simply put, the convenience and price advantage afforded by industrial food does not justify the suffering to which industrial farm animals are subject. It cannot, unless we are prepared to invert the concepts of both suffering and justification: modern factory farms are hellhouses of animal suffering writ large. The literature with which vegetarians and vegans often make their points, while wrong in its desired outcome, is nonetheless correct about the circumstances it unveils. Pig factory farming, in particular, is a uniquely brutal form of torture to inflict upon a very intelligent type of animal, cramming pigs into slum tenement conditions, forcing pregnant sows into brutal gestation crates, and creating conditions ripe for the abuse of animals. Cows are forced into similar crowded conditions on their own factory farms and made to eat a diet of grain that makes them sick, and they must wade around in knee-deep, toxic sea of their own waste while they’re doing it. Chickens raised for meat in an industrial setting are, as usual, crowded into impossibly dense conditions, and they often suffer from skeletal problems and organ failure due to how fast they grow; their lot, however, is roses compared with laying hens, which are subject to conditions that can only be described as nightmarish.

And of course, the industrial farm feeds into the industrial slaughterhouse, which is usually the apex of factory farm suffering. It is almost impossible to have avoided seeing at least one surreptitious PETA video of industrial abattoirs—and what one usually sees is unmitigated misery in shocking abundance. Surely many animals enter and exit the slaughterhouse with blessed unawareness; it is doubtless that many are processed with a Prussian efficiency that allows for minimal suffering. Nevertheless, the industrial system has permitted animal agony in spades, and it has shown little inclination to curb the worst of its abuses in any systematic sense. That is to say, the system itself begets the problems, and the overseers of factory farming have no desire to change the system.

No Need For Government Regulation

The standard response for many is to stop eating meat, or, if you’re an utterly simpleminded Progressive or left-liberal, to call for more government regulation of the agriculture industry (as if it wasn’t already regulated enough). There is a better solution, one that acknowledges the healthy benefits and the basic ethicality of eating meat and also recognizes the flagrant inability of the U.S. government to do anything right. Humanely-raised meat does not allow for these savage abuses of morality and of nature’s and God’s design. Most humane farmers, after all, are, well, humane, and in any event there is no efficiency in abusing your animals within these types of operations: when nature is respected and good ethics are followed, you tend not to have any need or desire to be cruel to your livestock.

It is true that this type of eating is more expensive, and there are a number of reasonable objections to a heftier price tag for any kind of food. One of the most frequent that I have heard, for instance, is that local, humanely-raised meat is too expensive for poorer people to purchase, so we should not encourage it as a viable agricultural model. This is a concerning and valid complaint to the higher expense to be found in humane meat, and we should certainly be aware of the price tag that can act as a barrier for low-income people to buying any good product. Nevertheless, poor peoples’ tight budgets are a strange reason to beg off doing the right thing yourself, and in any event most of the things we take for granted today, such as refrigerators and dishwashers and computers, were at first completely unaffordable for the poor.

More farmers, and hence more competition, may lower the price of such food in the future; it is also worthwhile to fight against asinine government regulations that make good meats harder and more expensive to obtain for rich, middle-class, and poor people alike. In the meantime, if you can afford humane meat, you should buy it. With all due respect to low-income folks, it is fairly silly to try and align your purchasing habits with the poor in order to effect an odd display of solidarity with them. Even poor people would probably agree.

This kind of devotion to ethical treatment can be taken too far (to vegetarianism or veganism, say), but it doesn’t have to be. I have eaten factory-farmed meat on numerous occasions when nothing else was available. I will not go hungry or lightheaded in order to prove a point. I do try and eat as best as I can whenever I can: like Harvey Ussery, the modern guru of small-scale chicken farming, I try and eat seafood if there is no “good” meat available, usually when I’m on the road, if only because the seafood I eat is usually wild-caught and, from what I understand, much less prone to feel pain and suffering than are land animals. Nevertheless, all but a vanishing fraction of my meat and dairy products come from the type of farms I feel are best for both the animals and for the ethical justification of eating them

There are a host of other reasons to eat like this; it supports the farmers, for one (American industrial farming rests upon an impossibly idiotic set of economic pillars, and American industrial farmers can barely make enough money off of their product to survive); there is also abundant evidence that grass-fed beef, for one, is far healthier than its industrial cousin. That being said, the best initial reason to start eating humanely is that switching to this kind of meat will end a great deal of physical agony and psychological torment for a great number of animals. Contra the bumper sticker to which I was treated, “humane meat” is not “yuppie bullshit;” it is, rather, a wonderful recognition that the animals that provide us with healthy, life-giving food deserve not to be subject to torment and agony and immeasurable misery. Vegans and vegetarians may have a problem with dead animals, but for meat eaters, it is crucial that we consider them while they are alive.

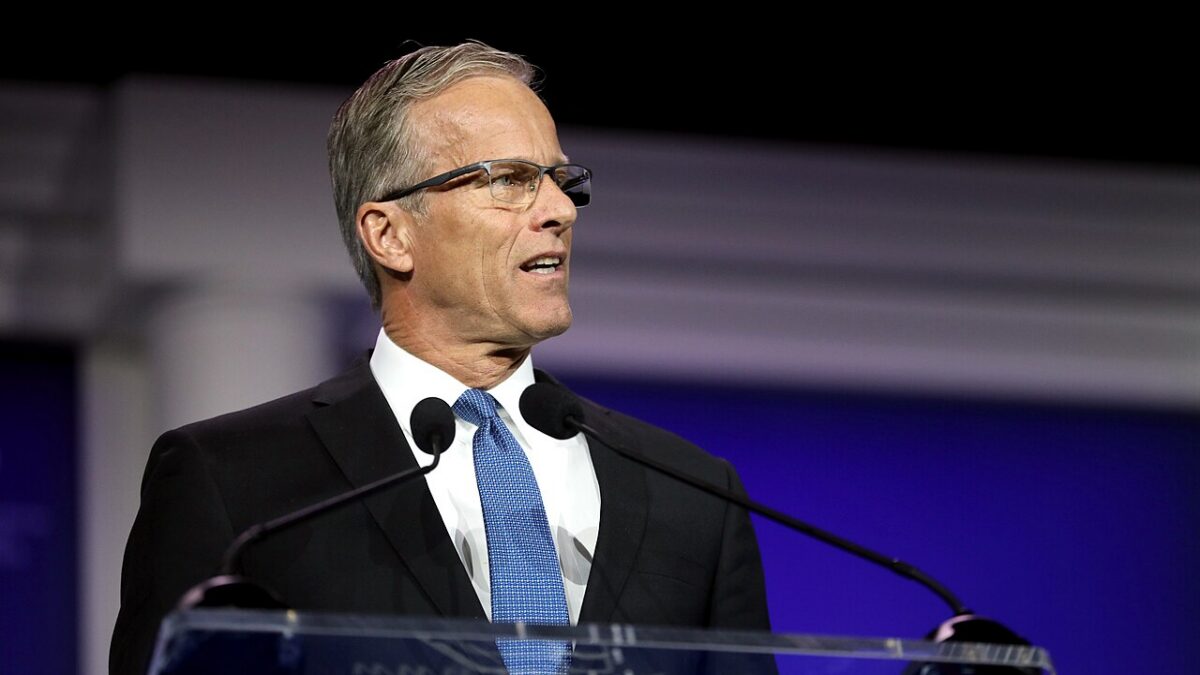

Daniel Payne is a senior contributor at The Federalist. He blogs at Trial of the Century. You can follow him on Twitter.

Editor’s note: This article has been modified to remove the epithet “illegal” from a description of undercover PETA videos.