Just days after being named CEO of Mozilla, Brendan Eich was forced out because he is an opponent of same-sex marriage. After declining opportunities to recant his views, he “voluntarily” decided to step down. Responses have been all over the map.

A writer at Slate actually tried to justify the termination as a good thing. Libertarian Nick Gillespie said he was “ambivalent” about Eich’s removal but that Eich’s resignation simply “shows how businesses respond to market signals.” And even conservatives weren’t rallying behind Eich on the grounds that marriage is an institution designed around sexual complementarity so much as by saying that even if he’s wrong, conscience should be protected.

At the end of the day, they’re all wrong. Or at least not even close to understanding the problem with Eich’s firing. Political differences with CEOs, even deep political differences, are something adults handle all the time. Most of us know that what happened held much more significance than anodyne market forces having their way. And Eich shouldn’t be protected on the grounds that one has the right to be wrong. See, Eich wasn’t hounded out of corporate life because he was wrong. He was hounded out of corporate life because he was right. His message strikes at the root of a popular but deeply flawed ideology that can not tolerate dissent.

And what we have in Eich is the powerful story of a dissident — one that forces those of us who are still capable of it to pause and think deeply on changing marriage laws and a free society.

Vaclav Havel and the Greengrocer

To explain, let’s revisit an old essay by Vaclav Havel, the Czech playwright, poet, dissident and eventual president. Havel, who died in 2011, was a great man of freedom, if somewhat idiosyncratic in his political views. He was a fierce anti-communist who was also wary of consumerism, a long-time supporter of the Green Party who favored state action against global warming, and a skeptic of ideology who supported civil unions for same-sex couples.

“The Power of the Powerless,” written under a communist regime in 1978, is his landmark essay about dissent. It’s a wonderful read, no matter your political persuasion. It asks everyone to look at how they contribute to totalitarian systems, with no exceptions. It specifically says its message is “a kind of warning to the West,” revealing our own latent tendencies to set aside our moral integrity. Reading it again after the Eich dismissal, I couldn’t help but think of how it applies to our current situation in the States.

“The post-totalitarian system demands conformity, uniformity, and discipline,” Havel wrote, using the term he preferred over “dictatorship” for the complex system of social control experienced in Czechoslovakia. We also have a system that is demanding conformity, uniformity and discipline — it’s not just about marriage law, to be honest. It’s really about something much bigger — crushing the belief that the sexes are distinct in deep and meaningful ways that contribute to human flourishing. Obviously marriage law plays a role here — recent court rulings have asserted that the sexes are interchangeable when it comes to marriage. That’s only possible if they’re not distinct in deep and meaningful ways. But the push to change marriage laws is just one part of a larger project to change our understanding of sexual distinctions. See, for example, the 50 genders of Facebook or the refusal to understand how women’s distinct career choices explain virtually all of the supposed pay gap that partisans exploit for political gain.

To explain how dissent works, Havel introduced the manager of a hypothetical fruit-and-vegetable shop who places in his window, among the onions and carrots, the slogan: “Workers of the world, unite!” He’s not actually enthusiastic about the sign’s message. It’s just one of the things that people in a post-totalitarian system do even if they “never think about” what it means. He does it because everyone does it. It’s what you do to get along in life and live “in harmony with society.” (For our purposes, you can imagine that slogan is a red equal sign that you put up on your Facebook page.)

The subtext of the grocer’s sign is “I do what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me.” It protects him from supervisors above and informants below.

Havel is skeptical of ideology. He says that dictatorships can just use raw power, but “the more complex the mechanisms of power become, the larger and more stratified the society they embrace, and the longer they have operated historically … the greater the importance attached to the ideological excuse.” We don’t have a dictatorship, obviously, but we do have complex mechanisms of power and larger and more stratified society.

In any case, individuals need not believe the lies of an ideology so much as behave as though they do, or at least tolerate them in silence or get along with those who work with them. “For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system, fulfill the system, make the system, are the system,” Havel says.

Wait a minute: What lies? What system?

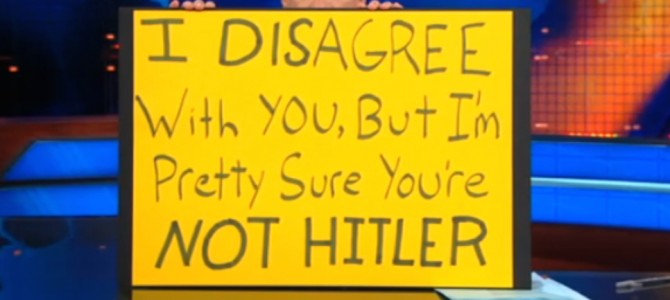

OK, let’s step back. What does any of this have to do with views on marriage? Well, I know that we’ve had years of criminally one-sided media coverage, cowardly political leaders and elite cultural views that have conveyed to you that the only reason anyone might think sexual complementarity is key to marriage is bigotry. You may have even internalized this message. You may need to hold on to this belief for reasons of tribalism or pride. But in the spirit of Jon Stewart’s poster shown up at the top, which reads, “I may disagree with you but I’m pretty sure you’re not Hitler,” let’s go on an open-minded journey where we seek to understand the views of others without characterizing them as Hitler-like. It’s difficult in these times, but we can do it.

OK. We probably already understand relationships have value, right? Assuming we’re not sociopaths, we do. So what is the difference between marriage and other relationships? There’s no question marriage has been treated dramatically differently than other relationships by governments and society. Why? Is it that it features a more vibrant or emotional connection? Or is there some feature that is a difference in kind – that marks it out as something that ought to be socially structured? We usually don’t want government in our other relationships, right? So why is marriage singled out throughout all time and human history as a different type of recognized relationship?

Well, what singled it out was that sex was involved. Sex. Knocking boots. The bump and grind. Dancing in the sheets. Making the beast with two backs. Doing the cha-cha. And so on and so forth. And why does that matter? Well, there’s precisely one bodily system for which each of us only has half of the system. It’s the one that involves sex between one man and one woman. It’s with respect to that system that the unit is the mated pair. In that system, it’s not just a relationship that is the union of minds, wills or important friendships. It’s the literal union of bodies. In sexual congress, in intercourse between a man and a woman, you are literally coordinated to a single bodily end.

In every other respect we as humans act as individual organisms except when it comes to intercourse between men and women — then we work together as one flesh. Coordination toward that end — even when procreation is not achieved — makes the unity here. This is what marriage law was about. Not two friends building a house together. Or two people doing other sexual activities together. It was about the sexual union of men and women and a refusal to lie about what that union and that union alone produces: the propagation of humanity. This is the only way to make sense of marriage laws throughout all time and human history. Believing in this truth is not something that is wrong, and should be a firing offense. It’s not something that’s wrong, but should be protected speech. It’s actually something that’s right. It’s right regardless of how many people say otherwise. If you doubt the truth of this reality, consider your own existence, which we know is due to one man and one woman getting together. Consider the significance of what this means for all of humanity, that we all share this.

Now if one wants to change marriage laws to reflect something else, that’s obviously something that one can aim to do. We’ve seen the rapid, frequently unthinking embrace of that change in recent years, described one year ago in the humanist and libertarian magazine Spiked as “a case study in conformism” that should terrify “anyone who values diversity of thought and tolerance of dissent.”

Perhaps there should have been a bit of a burden of proof on those who wanted to change the institution — something beyond crying “Bigot!” in a crowded theater. Perhaps advocates of the change should have explained at some point, I don’t know, what singles out marriage as unique from other relationships under this new definition. What is marriage? That’s a good question to answer, particularly if you want to radically alter the one limiting factor that is present throughout all history. Once we get an answer for what this new marriage definition is, perhaps our media and other elites could spend some time thinking about the consequences of that change. Does it in any way affect the right of children to be raised by their own mother and father? Have we forgotten why that’s an important norm? Either way, does it change the likelihood that children will be raised by their own mother and father? Does it by definition make that an impossibility for whatever children are raised by same-sex couples? Do we no longer believe that children should be raised by their own mother and father? Did we forget to think about children in this debate, pretending that it’s only about adults? In any case, is this something that doesn’t matter if males and females are interchangeable? Is it really true that there are no significant differences between mothers and fathers? Really? Are we sure we need to accept that lie? Are we sure we want to?

Welcome to the mob

“Part of the essence of the post-totalitarian system is that it draws everyone into its sphere of power,” writes Havel. We create through our involvement a general norm and, thus, bring pressure to bear on our fellow citizens. We learn to be comfortable with our involvement, “to identify with it as though it were something natural and inevitable and, ultimately, so they may—with no external urging—come to treat any non-involvement as an abnormality, as arrogance, as an attack” on ourselves.

There’s much to be thankful for in aftermath of the madness of the Eich termination. For one thing, many people have rightly figured out that what happened there is terrifying. It’s not just natural marriage advocates but even some of same-sex marriage supporters most vocal advocates. I’m reticent to point it out but Andrew Sullivan took a break from vilifying natural marriage advocates, a long-time specialty of his, to wonder if maybe things had gotten completely out of control. William Saletan wrote an important satirical piece that noted the absurdity of these types of witch hunts. And Conor Friedersdorf criticized Mozilla’s hypocrisy and worried about the dangerous precedent that was set.

Far more than the political folks on either side, though, is the importance of what happened to the apolitical. In one sense, the most frightening aspect of the Eich termination was the message it sent to people throughout the country: Shut up or you will lose your livelihood. But in another sense, this dissident moment may spark something previously thought impossible.

Havel says that party politics and the law are the weakest grounds on which to fight against group think. Instead, he says that the real place for dissidents to fight for freedom is in the space where the complex demands of the system affect the ability to live life in a bearable way — to not be fired for one’s views, for instance. “People who live in the post-totalitarian system know only too well that the question of whether one or several political parties are in power, and how these parties define and label themselves, is of far less importance than the question of whether or not it is possible to live like a human being,” Havel said.

Plastic People of the Universe

He brings up the example of the avant-garde, Velvet Underground-inspired band Plastic People of the Universe. The members refused to abide by strict controls on art and personal appearance, even when encouraged to by governing authorities. “They had been given every opportunity to adapt to the status quo, to accept the principles of living within a lie and thus to enjoy life undisturbed by the authorities. Yet they decided on a different course. Despite this, or perhaps precisely because of it, their case had a very special impact on everyone who had not yet given up hope.”

The freedom to play rock music was understood as a universal freedom. And not standing up for others’ freedom meant you were surrendering your own.

It’s in this sense that Eich’s most important political work was not making a paltry $1,000 donation in defense of natural marriage laws. It was in refusing to recant.

Consider first the response of one of the activist’s calling for Eich’s head. After he resigned, activist Michael Catlin wrote that he never thought his campaign against Eich would go “this far” and that he wanted “him to just apologize.” So he was “sad” that Eich didn’t say the magic words that would have allowed him to keep his job. Yeah, he really said that.

And then think about how horrified people were that Eich lost his job for his views that men and women are different in important ways. Regardless of our previous views on marriage, we saw in Eich a dissident who forced us to think about totalitarianism and our role in making society unfree. Did we mindlessly put up red equal signs when we hadn’t even thought about what marriage is? Did we rush to fit in by telling others we supported same-sex marriage? Did we even go so far as to characterize as “bigots” or as “Hitlers” those who held views about the importance of natural marriage?

I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient

In the greengrocer scenario, Havel notes that if the text of the sign read “I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient,” he might be embarrassed and ashamed to put it up. The dissidents are the ones who, by refusing to put the sign up, or refusing to recant, shine a huge light on the system, including the ones who go along to get along. All of a sudden those Facebook signs, those reflexive statements, those cries of “Bigot!” look less like shows of strength and more like shows of weakness.

Why was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn driven out of his own country, asks Havel. It wasn’t because he had political power:

Solzhenitsyn’s expulsion was something else: a desperate attempt to plug up the dreadful wellspring of truth, a truth which might cause incalculable transformations in social consciousness, which in turn might one day produce political debacles unpredictable in their consequences. And so the post-totalitarian system behaved in a characteristic way: it defended the integrity of the world of appearances in order to defend itself. For the crust presented by the life of lies is made of strange stuff. As long as it seals off hermetically the entire society, it appears to be made of stone. But the moment someone breaks through in one place, when one person cries out, “The emperor is naked!”—when a single person breaks the rules of the game, thus exposing it as a game—everything suddenly appears in another light and the whole crust seems then to be made of a tissue on the point of tearing and disintegrating uncontrollably.

Whether Eich and other dissidents will crack our thick, hardened crust remains to be seen. Perhaps there will need to be dozens, hundreds, thousands more dissidents losing their livelihoods, facing court cases, and dealing with social media rage mobs. But all of a sudden, the crust doesn’t seem nearly as impenetrable as it did last week.