It is 63 degrees in Houston in January, and we head to Challenger Seven Memorial Park for my son’s orienteering event, part of his seventh grade leadership development course. We are in Webster, not far from NASA. The sun is bright, and you can still see last night’s pale moon hanging in the blue sky. There are no clouds, but you can see the wind blowing things around, and I can feel Christopher’s excitement. It is a little competition: You are supposed to explore unfamiliar terrain with only a map. You are supposed to move fast, competing with the clock. It is a race against time.

I leave him with his group of boys and Captain Troutt, and I start walking around. I pass the trees with the moss hanging down, making my way to where the canoes can glide down Clear Creek. Then I start running, leaving the pavement and hitting the trails. I pass the birders, with their khaki pocketed vests, their binoculars, and their infinite and magnificent patience. There are so many birds singing, I cannot believe it. I think of John Keats knowing he is going to die, writing about the nightingale singing “in full-throated ease.” Those birds have to glide, must sing, no matter what. I feel lucky: I see a red cardinal, and it is only January.

I run faster, and come to a mound of earth with a plaque. It is called “Mother Earth” and had dozens of people support its commission. All I see is a big sign that gives orders stating “don’t ride bicycles” on it. I know why: You see this mound and all you want to do is buy a mountain bike and ride it right down the hilly parts of it. I have to walk around it a few times before I really see it: It is not just a mound of dirt. It is a formation of a woman lying down on her back looking up into space. Sometimes it takes awhile for you to really see something. But when you do, you don’t forget it.

I walk back to get Christopher, named after the patron saint of travel, and I see the commemorative plaque for the seven astronauts lost when the Challenger exploded on January 28, 1986. I read that the plaque was presented by the Texas A & M corps honoring the fallen, and that they formed a group of seven students to honor the dead, keep their excellence alive. I read the names: Francis R. Scobee, Michael J. Smith, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Greg Jarvis, and Christa McAuliffe. I remember thinking that I wished Christa McAuliffe had been my science teacher, and how amazing it was that she was so good at teaching science that she was able to go into space. She must have had that rare combination of knowledge and fearlessness that is required for heroic measures. I remember the explosion, the shock, the sadness. I was a sophomore in college. Like most Americans, it was hard to believe, hard to take. As I am writing this, The Huffington Post reports on “Never-Before-Seen Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster Photos Found in Granddad’s Old Boxes,” and I realize how jarring such a tragedy is, and that it never goes away. I am glad for the discovery no matter how much I hate the wording: I am glad it is not forgotten.

I walk toward the students, who have finished their course, who in their own way have gone where they have never gone before. They are happy with their explorations, the things they discovered that they had no idea existed. They are all about twelve and thirteen, between innocence and experience. They are not on their cell phones, they are not thinking about Miley Cyrus, they are miles away from computer games and the cruelty of junior high. They are in sunlight at Challenger Park, walking the grass, seeing squirrels, mapping out the world. They are moving fast, but in the luxury of thinking they have all the time in the world. I teach literature, and walking toward my son, I think of how literature tells us what we already know, but don’t always have the language to convey. It is a different kind of transport. But the scientist and the explorer must have so much bravery: They are always in unfamiliar terrain, always going into the universe of the unknown. I show him the plaque. It is hard not to cry. But then I cannot help it. I do cry, because no matter how beautiful the park, no matter how many birds, this place is commemorating such a profound loss. Even the clear blue sky seems too small to hold all of that grief.

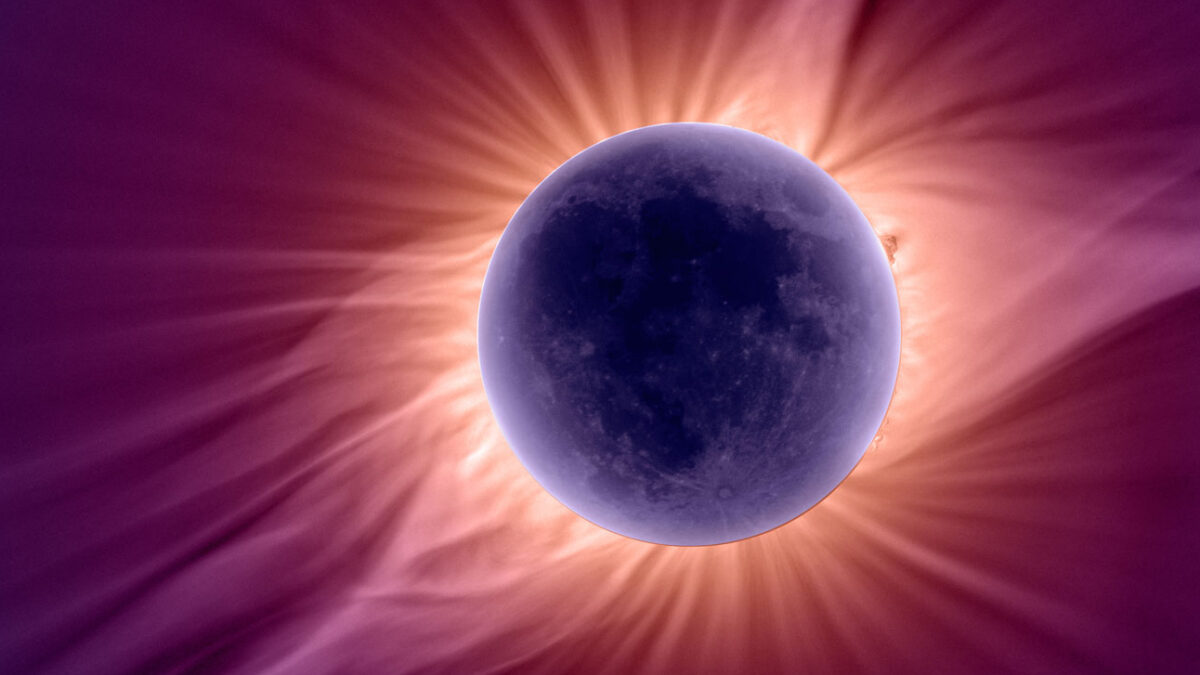

Christopher and I walk to the wetlands section, sit on an old board, and watch the regal egret, walking with such delicate hesitation before he alights and flies higher than I thought egrets could fly. I remember taking Christopher to the Houston Symphony playing “The Planets,” with those amazing pictures from the Hubble that never cease to astonish. I think of the astronauts launching off the coast of central Florida, the endless preparation, the anticipation of what they would see, the infinite hope. I remember the speeches, President Reagan saying, “We will never forget them, not the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of Earth’ to “touch the face of God.’”

I think of the bravery of space exploration, the explorers who have been closer to the other planets, the thrill and the fear, the distance from earth and all that we know. President Reagan reminded us when he was commemorating these seven men and women that “Sometimes, when we reach for the stars, we fall short. But we must pick ourselves up again and press on despite the pain.” Christopher and I walk around, look at the glimmering water, head back to the car. It is so warm for January, the sun is so bright, the sky never ending. It is one of those days when you think that everything is possible.

Doni M. Wilson is an Associate Professor of English at Houston Baptist University and a contributor to Reflection and Choice.