A 5-4 Supreme Court case decided on strict textualist grounds is usually accompanied by weeping and gnashing of teeth among the corporate press. The narrowly decided case of McGirt v. Oklahoma somehow escaped that treatment, and the court avoided the calumnies typically heaped upon it. The reason is that reactions change based on results rather than principles, and the McGirt decision was by the four left-leaning justices and one right-leaning one.

In McGirt, the court held that the Indian reservations of what we used to call the “Five Civilized Tribes” were never formally dissolved, even though the land they encompassed — most of the eastern half of Oklahoma — has been populated by a majority non-American Indian population for decades. The demographics and pattern of settlement do not look like that of an Indian Reservation, but courts do not decide what things look like, they decide what things are.

What they are is determined by the law. In his opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch focused not on the beliefs of the residents or officials in that region, which are neither measurable nor dispositive, but on the acts of Congress. Congress establishes reservations and only Congress may disestablish them.

In finding that Congress had never disestablished the Creek Reservation, the court complicates the legal regime of half of a state, yet it does so because of its constitutional duty to interpret the law as written. Regardless of whether the result is deemed to be “liberal” or “conservative,” that demand remains.

Mustering the Will

Whatever you think of his other recent decisions, Gorsuch is without a doubt one of the court’s most talented writers. In McGirt, his summary of the complex legal history of the region is accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike.

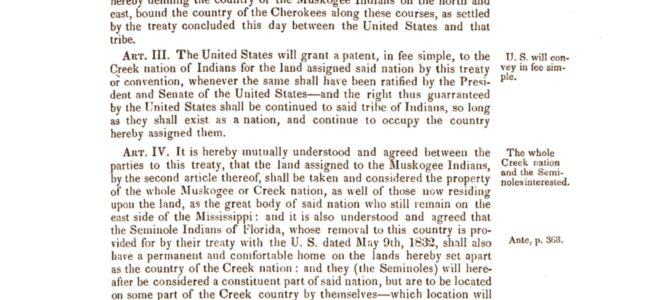

First, the court had to determine whether the land in question was a part of an Indian reservation. Indisputably, at one time it was. In furtherance of the Indian removal policy of President Andrew Jackson, the five tribes in question — the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole — were compelled to accept expulsion from their lands. They were granted lands west of the Mississippi and forced to travel there in the now-infamous Trail of Tears.

Those lands, in present-day Oklahoma, were promised to them in perpetuity. Like all laws, this one was permanent only as long as Congress did not change its mind and pass a different law. In many other parts of the country, Congress did just that, and lands that were once part of Indian Country were removed from tribal control and opened to white settlement.

The question in McGirt was not whether Congress had the power to disestablish a reservation, but whether they had actually done so. Gorsuch found that Congress had done quite a bit to weaken the tribe’s jurisdiction, but it had never officially and explicitly terminated the reservation as required.

“History shows that Congress knows how to withdraw a reservation when it can muster the will,” Gorsuch writes. But in all of the years since the Creek reservation was established, it never did so. “Whatever the confluence of reasons,” he concludes, “in all this history there simply arrived no moment when any Act of Congress dissolved the Creek Tribe or disestablished its reservation.”

Weighing Actions Versus Law

Against the lack of congressional action, the four dissenting justices, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, emphasize a great many actions that, in their reckoning, add up to an implicit reduction of the Creek reservation. Beyond that, they note, recognizing the reservation’s original borders will have dramatic, unforeseen results for the people living there.

They are not wrong about the events that transpired, even if the results they prophesy are exaggerated. Congress did reduce tribal authority over the reservation. They divided up much of the land that was held collectively and allowed individual tribal members to own it. They further allowed those owners to sell the land to anyone they wanted, including people who were not American Indians.

These and other changes altered the character of the reservation, and since Oklahoma achieved statehood, state and federal government officials increasingly acted as if much of the former land of the Five Civilized Tribes was no longer the possession of the American Indians to whom it was promised.

But if we treated this as a repeal of the law, Gorsuch points out, it would lead to truly perverse incentives in government. He imagines the problems with this course of inaction-as-action:

A State exercises jurisdiction over Native Americans with such persistence that the practice seems normal. Indian landowners lose their titles by fraud or otherwise in sufficient volume that no one remembers whose land it once was. All this continues for long enough that a reservation that was once beyond doubt becomes questionable, and then even farfetched. Sprinkle in a few predictions here, some contestable commentary there, and the job is done, a reservation is disestablished. None of these moves would be permitted in any other area of statutory interpretation, and there is no reason why they should be permitted here. That would be the rule of the strong, not the rule of law.

Words Matter

Gorsuch’s reasoning is correct here: if the text is ignored every time it is violated, the law will no longer exist. That is why laws are written down, and why textualism is the only legitimate means of interpreting them. As to the difference between textualism and originalism, there is almost none. I endorse Professor Ilan Wurman’s view that they mean essentially the same thing.

This method of interpretation will usually lead to a conservative result, but not always. The reasoning is somewhat circular: because conservatives want judges to interpret the law as it is written, judges who do so are called conservative.

But if the law as written is liberal — even more liberal than the current consensus about the law’s subject — the result is otherwise. A conservative judge would be compelled by the law to give a liberal opinion. That is what Gorsuch has done here, and it is hard to see how a committed textualist could have done otherwise.

If you had polled the citizens of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and asked them whether the land they lived on was, in 2020, a part of “Indian country,” I suspect their answers would have been an overwhelming and resounding “no.” But the law does not come from polls, it comes from statutes.

Textualism is correct not because it is conservative but because it is true. Gorsuch deserves credit for acknowledging that, even when some of his judicial allies try to forget it when it is inconvenient.