Early polling indicated Gov. Newsom’s Proposition One, which adds $6.4 billion in debt to fund housing and mental health beds for the chronically homeless, would easily pass. However, 49.8 percent of voters saw through the shenanigans, nearly delivering the governor a stunning rebuke.

Could this be the beginning of the end of “Housing First”?

Prop One sounded compassionate. However, the devil was buried deep into the measure’s 68 pages of detail: “Housing interventions must comply with the core components of Housing First.” Newsom spent $21 million to camouflage the measure as a “game changer.” The opposition raised around $2,000. So why did the measure nearly fail?

Some claim voters were rejecting additional bond debt. Others claim voters have exhausted their compassion. However, it appears about half of California voters have had enough of failure, and the governor who continues to champion it. They no longer trust his promises to reduce homelessness — promises that started more than a decade ago as San Francisco’s mayor.

They didn’t have to read the 68 pages to know Prop One was another empty promise.

They were right.

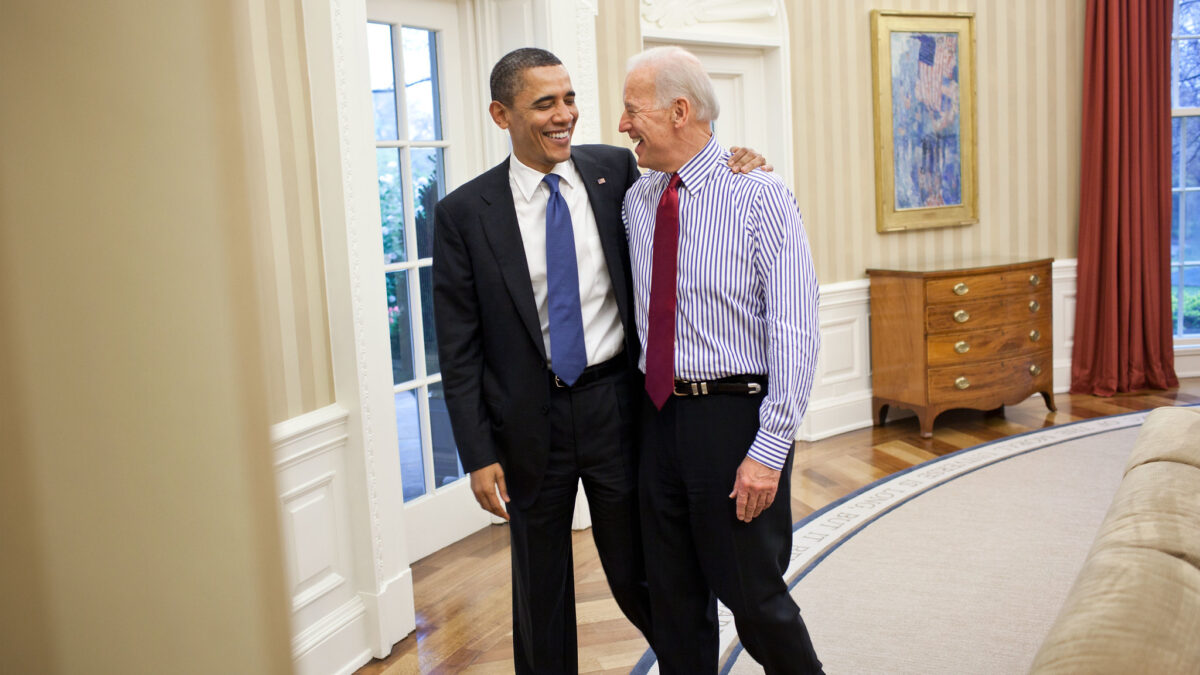

California followed the federal government in adopting Housing First as a one-size-fits-all approach to homelessness, embedding it into state statute in 2016, despite insignificant signs of headway. When President Obama formally adopted Housing First in 2013, he promised the seismic policy shift would end homelessness in 10 years.

Housing vouchers became the primary tool in the homelessness toolbox while funding for clinical services such as mental health and addiction counseling was drastically reduced, as was funding for employment training. The money saved was used to dole out additional vouchers for permanent housing with no strings attached.

Requirements such as sobriety, chores, and work participation became “barriers” under this approach, as they 1) might preclude a homeless individual from accepting housing and 2) were not needed because the homeless could “self-determine” their need for services once stably housed.

Today — 10 years later — homelessness has not ended. It has reached its highest point ever, as has its death rate. California now lays claim to 30 percent of the nation’s homeless population and 50 percent of its chronically homeless population.

Having spent 13 years on the front lines serving homeless women and children in Sacramento, California, I would have been among the “no” votes.

Seventy-eight percent of the homeless struggle with mental illness and 75 percent with addiction, whether a precursor to, or a result of, their homelessness. According to the U.S. surgeon general, these diseases are complex brain disorders that can reduce brain function and inhibit an individual’s ability to make decisions and regulate action.

In combination with a disease called anosognosia — a deficit of self-awareness with which the majority of the mentally ill and addicted also struggle — it becomes extremely unlikely that the homeless will engage in services once housed.

A 14-year study of Boston’s chronically homeless population demonstrated exactly that. Housing without required services was a death sentence for nearly half of the housed. Only 36 percent remained housed after year five.

Our clients struggled with similar illnesses: around 78 percent with addiction and close to 60 percent with mental illness. We provided them with a clean and sober environment so they could gain clarity, recover, build a supportive community, and thus begin their transformation.

Clients were required to engage in clinical services, which proved to be especially important in the initial months, a period during which they were still emerging from the dense fog of mental illness, addiction, or both. Within 18 months, our graduates exited our program employed and capable of providing for their families. Dozens have become homeowners, a rigorous feat for a single mother in California.

Had sobriety and services not been required, our outcomes would have likely mirrored Boston’s.

Prop One advocates may be happy squeaking out a nail-bitingly close victory this time, but the narrow margin for this well-funded measure in dark-blue California signals a turning tide against a failed approach to housing policy.

While the governor continues to cleave to a “housing only” strategy, nearly half of his constituency recognized that the provision of more housing for the homeless, without funding for services and without conditions, should not be the final chapter in the book.

It ignores one of life’s fundamental realities: “Either we grow, or we die.”